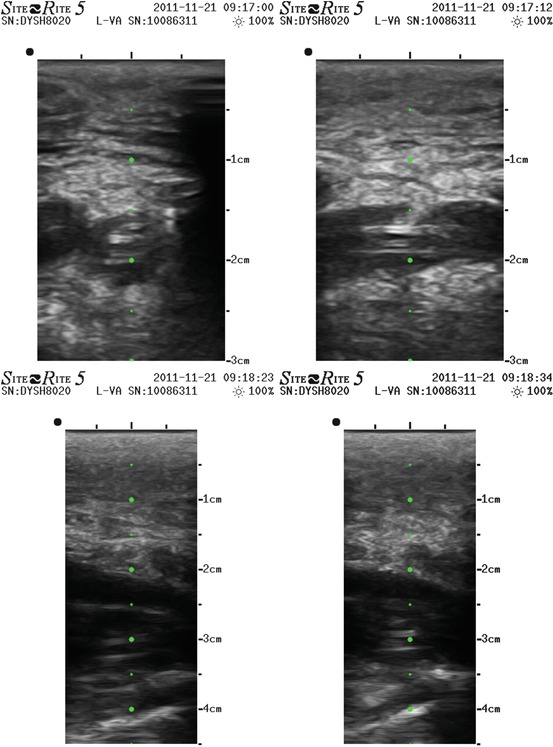

Figs. 10.1 and 10.2

Echographic image of a PICC surrounded by thrombus in axillary vein, transverse and longitudinal section

This test is considered diagnostic if positive and does not need further evaluation with more invasive diagnostic tools, according to the above cited ACCP guidelines and to less recent but still valid guidelines and reviews [42, 43]. Initial evaluation in case of clinical suspicion or high-risk patients must be available in any PICC team with echographic-trained personnel.

10.3 Therapy

For what concerns the treatment of a PICC-related deep vein thrombosis, we refer to the above cited ACCP guidelines (Chest 2012), to the international guidelines for CVC-related thrombosis in patients with cancer [29], and to the review “Management of occlusion and thrombosis associated with long-term indwelling central venous catheters” (Baskin, Lancet 2009).

In particular:

The catheter must not be removed if functional and needed and if its tip is correctly positioned.

Early removal of the catheter is necessary only in case of pulmonary embolism or infected thrombophlebitis.

In any other case, removal of the catheter must be preceded by 3–5 days of effective anticoagulation (Figs. 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7 and 10.8).

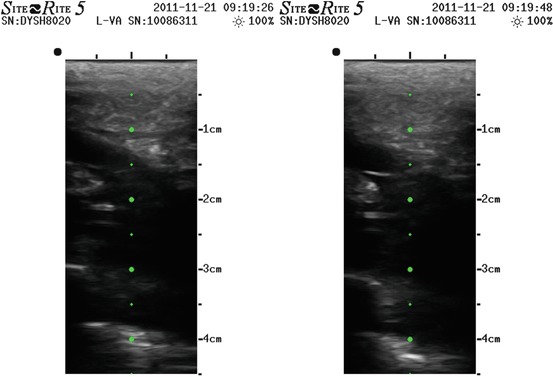

Figs. 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7 and 10.8

Echographic image of a PICC surrounded by thrombus in brachial vein, extended in axillary and subclavian till the confluence with internal jugular vein

Acute anticoagulation must be performed with full-dose LMWH or fondaparinux.

Long-term full-dose anticoagulation in oncologic patients is mandatory with LMWH or fondaparinux; for non-oncologic patients, VKAs can be considered.

Anticoagulation must be continued as long as the catheter is maintained.

The duration of anticoagulation after catheter withdrawal is still debated.

The grades of evidence for the advised therapies reported in ACCP guidelines 2012 are:

For the treatment of superficial vein thrombosis (basilic vein is considered by some authors as a “large vein,” not a “deep vein”): prophylactic dose of fondaparinux or LMWH for 45 days (Grade 2B)

For the acute anticoagulation for upper arm deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT): parenteral anticoagulation with UEDVT or fondaparinux (Grade 1b)

For the long-term anticoagulation for UEDVT: if CVC-related, not to remove catheter if functional and needed (Grade 2C); anticoagulation as long as the catheter is maintained in situ (Grade 1C for oncologic patients, Grade 2C for other patients); minimum duration of anticoagulation of 3 months if catheter is removed (Grade 2B)

10.4 Prevention

Efforts to use pharmacologic prophylaxis with heparin, ASA, or warfarin to reduce catheter-related DVT have not resulted in any consistent conclusion [36, 37]. In particular, a 2008 huge meta-analysis about thromboprophylaxis for patients with cancer and central venous catheters reports that the balance of benefits and downsides of thromboprophylaxis in cancer patients with CVC remains uncertain [38]. More recently ACCP guidelines 2012, dealing with patients with cancer and indwelling central venous catheters, suggest evidence against routine prophylaxis with LMWH or LDUH (Grade B) and VKAs (Grade 2C); on the contrary, for patients with additional thrombosis risk factors, a prophylactic dose of LMWH or LDUH is suggested (Grade 2B).

Other studies aimed to reduce complications of central venous catheterization led to the development of techniques, such as real-time ultrasound guidance, that minimizing the traumatism on endothelium in fact reduced the risk of developing catheter-related thrombosis [39].

With the widespread diffusion of new positioning techniques, the evolution of materials and technology of devices, and the development of new intravenous oncologic therapies, the diffusion of central venous access in the last 20 years has importantly grown; for this reason, medium- and long-term complications are more and more observed, and a lot of effort has been made in finding a way to prevent them.

Many reviews and meta-analysis have been published on risk factors, prevention, and treatment of CVC-related thrombosis [4, 6, 9, 29, 44]; the huge heterogenicity of studies design and inclusion criteria led to scarcely important indications, as the identification of risk factors turned out to be very different from study to study.

In 2007 the Italian consensus group for central venous access (GAVeCeLT) published on JAVA a paper concerning the catheter-related central venous thrombosis (“the development of a nationwide consensus paper in Italy”) [40], more recently focused on PICC-related complications, that can be referred to as a “bundle” for prevention.

As regards prevention, according to ACCP 2012 guidelines, SOR 2008 guidelines, international 2012 guidelines for CRDVT in cancer patients, and GAVeCeLT consensus, we suggest the following points:

Echographic complete evaluation of all upper limb and neck veins, in order to identify the bigger and straighter vein to be cannulated.

Preferential right side approach.

Avoiding paretic arm when possible.

The smallest needed catheter in the biggest vein.

Real-time ultrasound guidance.

Aseptic technique of positioning and maximal barrier protection.

Correct localization of catheter tip in proximity of atriocaval junction, when possible with ECG intracavitary technique.

Catheter stabilization with sutureless devices.

Careful maintenance of the catheter for preventing infections.

For patients with additional risk factors (previous DVT, sepsis, cancer + another DVT risk factor), a prophylactic dose of LMWH or LDUH can be considered.

References

1.

Kalso E (1985) A short history of central venous catheterization. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 81:7–10CrossRef

2.

3.

4.

5.

Pikwer A, Akeson J, Lindgren S (2004) Complications associated with peripheral or central routes for central venous cannulation. Anaesthesia 67:65–71CrossRef

6.

Verso M, Agnelli G (2003) Venous thromboembolism associated with long-term use of central venous catheters in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 21(19):3665–3675PubMedCrossRef

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree