Chapter 12 Clinical electrocardiography and arrhythmia management

This chapter examines the clinical use of the ECG, one of the most important diagnostic tools in an emergency department. It must be stressed, however, that the ECG may appear normal, even in the presence of severe cardiac disease.

ECG INTERPRETATION

1 Chest and upper abdominal pain, dyspnoea, shock

History and examination are the mainstays of assessment, with the ECG playing a complementary role. The main conditions requiring early diagnosis are acute myocardial infarction (AMI), unstable angina, aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism (PE).

Myocardial infarction

Note that the initial ECG may be normal in about half of patients with AMI.

ST elevation

Q waves

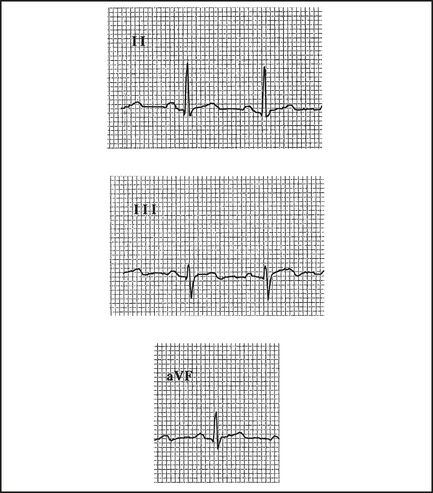

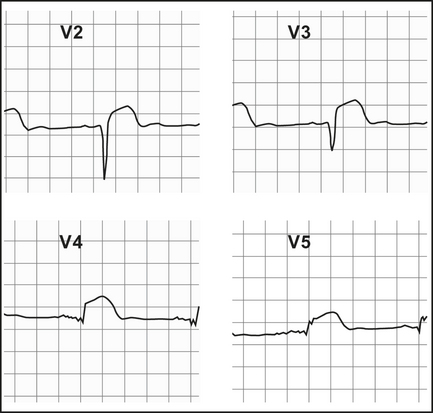

Q waves > 2 mm, > 40 ms follow in those leads showing ST elevation, if the infarct evolves (Table 12.1). They may appear within the first hour or, more commonly, within 2–6 hours (Figure 12.2). Differentiate from nonpathological septal Q waves in LI, LII, aVF or V5,V6, which are small (< 2 mm) and narrow.

Table 12.1 Infarct localisation—the ECG pattern distribution (early ST elevation, later Q waves)—will help to localise the site of infarction, and the usual coronary artery occluded

| ECG pattern distribution | Site | Infarct-related artery |

|---|---|---|

| I, aVL | Lateral | Circumflex |

| II, III, aVF | Inferior | Right coronary, circumflex |

| V2–4 | Anterior | Left anterior descending (LAD) |

| V1,2 (large R, ↓ST) | Posterior | Right coronary |

R wave

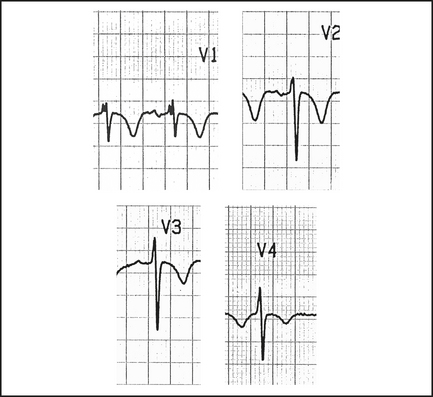

A prominent R wave in V1, and often V2, suggests a posterior infarct, as well as incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB), right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) or left accessory pathway.

Pulmonary embolus (PE)

Anticoagulation is indicated (see Chapter 10, ‘Pulmonary emboli and venous thromboses’). Consult urgently for compromised patients following massive PE as they may need urgent thrombolysis or embolectomy.

2 Collapse, palpitations, syncope, dizziness, altered consciousness

The ECG can help to determine a cardiac cause.

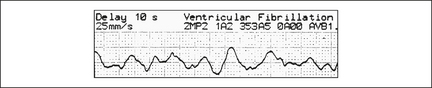

Ventricular fibrillation (VF)

This grossly irregular and variable amplitude arrhythmia is easy to recognise (Figure 12.4), unless it is low in amplitude, when it can be mistaken for asystole (if in doubt, treat as VF).

Rarely, continued ALS may still rescue a patient with a preterminal rhythm.