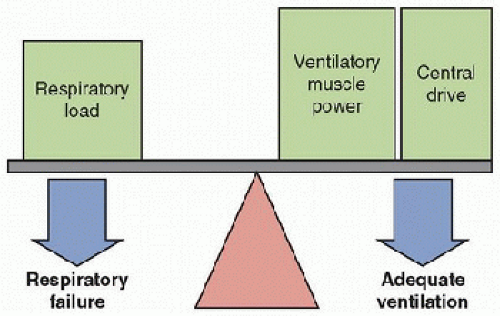

The respiratory system in children is immature and vulnerable to chronic respiratory failure. With respiratory disorders, ventilatory muscle power and/or central respiratory drive may not be adequate to overcome the respiratory load, resulting in respiratory failure.

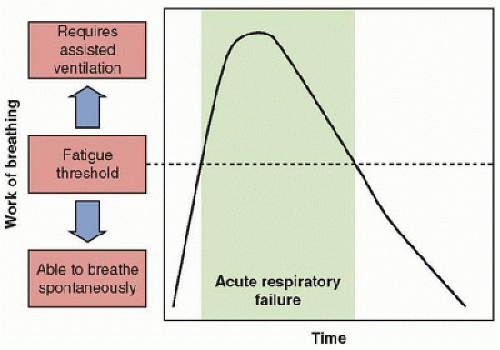

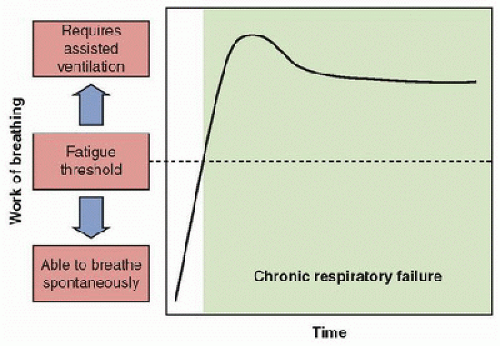

The respiratory system in children is immature and vulnerable to chronic respiratory failure. With respiratory disorders, ventilatory muscle power and/or central respiratory drive may not be adequate to overcome the respiratory load, resulting in respiratory failure. Chronic respiratory failure requires a different philosophy and strategy to treat optimally. As these children will not wean quickly from mechanically assisted ventilation, their ventilatory needs should be fully supported by the ventilator, and weaning (if possible) requires optimizing the function of the lungs, ventilatory muscles, and central drive.

Chronic respiratory failure requires a different philosophy and strategy to treat optimally. As these children will not wean quickly from mechanically assisted ventilation, their ventilatory needs should be fully supported by the ventilator, and weaning (if possible) requires optimizing the function of the lungs, ventilatory muscles, and central drive. Children with chronic respiratory failure can often be cared for at home. Candidates for home mechanical ventilation (HMV) must have a stable respiratory disorder that does not require frequent changes in ventilator settings.

Children with chronic respiratory failure can often be cared for at home. Candidates for home mechanical ventilation (HMV) must have a stable respiratory disorder that does not require frequent changes in ventilator settings. HMV is most commonly provided using positive-pressure ventilation via tracheostomy. However, some children are able to use noninvasive techniques (noninvasive positivepressure ventilation via mask, negative-pressure ventilation, or diaphragm pacing), which may permit removal of their tracheostomies.

HMV is most commonly provided using positive-pressure ventilation via tracheostomy. However, some children are able to use noninvasive techniques (noninvasive positivepressure ventilation via mask, negative-pressure ventilation, or diaphragm pacing), which may permit removal of their tracheostomies. Prior to hospital discharge, children using HMV and their families require thorough education, complete equipment including safety monitors, and arrangements for ancillary health care needs and community resources (school).

Prior to hospital discharge, children using HMV and their families require thorough education, complete equipment including safety monitors, and arrangements for ancillary health care needs and community resources (school). Once at home, children using HMV require ongoing medical care from an interdisciplinary team who can address medical, developmental, psychosocial, and equipment needs.

Once at home, children using HMV require ongoing medical care from an interdisciplinary team who can address medical, developmental, psychosocial, and equipment needs.Thus, the approach to managing CRF must be appropriate for home or chronic care facility settings. Chronic ventilatory support in the home is, for many patients, a safe and relatively inexpensive alternative.

Neurologic control of breathing must ensure adequate ventilation to meet the metabolic needs of the body during sleep, rest, and exercise. Ventilation varies with the state of the individual. It becomes less adequate during sleep, and it is less responsive to modulation by chemoreceptor input during rapid eye movement (REM) or active sleep. It is not surprising that sleep is the most vulnerable period for the development of inadequate ventilation in disorders of respiratory control (15,17,18). Immaturity of the respiratory control systems in the infant and young child predispose to apnea and hypoventilation. Furthermore, the infant spends ˜50% of sleep time in REM sleep (in contrast to 15%-20% spent by the adult), and an infant sleeps for a longer portion of the day. Active sleep is associated with greater variation in respiratory timing and amplitude, resulting in periods of inadequate gas exchange. Thus, CRF always includes inadequate gas exchange during sleep.

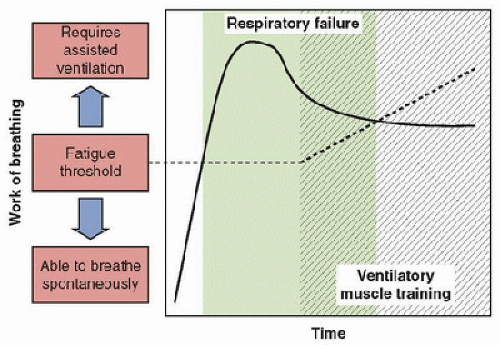

Neurologic control of breathing must ensure adequate ventilation to meet the metabolic needs of the body during sleep, rest, and exercise. Ventilation varies with the state of the individual. It becomes less adequate during sleep, and it is less responsive to modulation by chemoreceptor input during rapid eye movement (REM) or active sleep. It is not surprising that sleep is the most vulnerable period for the development of inadequate ventilation in disorders of respiratory control (15,17,18). Immaturity of the respiratory control systems in the infant and young child predispose to apnea and hypoventilation. Furthermore, the infant spends ˜50% of sleep time in REM sleep (in contrast to 15%-20% spent by the adult), and an infant sleeps for a longer portion of the day. Active sleep is associated with greater variation in respiratory timing and amplitude, resulting in periods of inadequate gas exchange. Thus, CRF always includes inadequate gas exchange during sleep.exchange (SpO2 ≥95% and end-tidal PcO2 [ETCO2] of 30-40 torr). The goal is to provide total ventilatory muscle rest. The patient is then removed from the ventilator for short periods of time during wakefulness approximately two to four times per day. In some cases, these initial sprints may last only 1-2 minutes. The child is carefully monitored noninvasively during sprints to identify hypoxia or hypercapnia, using pulse oximetry and ETCO2 monitoring. Increased supplemental oxygen, above that required on the ventilator, may be required during sprinting. Guidelines for terminating sprints, such as SpO2 <95% or ETCO2 >45-50 torr, should be provided as written orders. In addition, if the child develops signs of distress such as tachypnea, retractions, diaphoresis, tachycardia, hypoxia, or hypercapnia, the sprint should be stopped. Note that the child with a respiratory control disorder may not exhibit these signs of distress. The length of each sprint is increased daily as tolerated. The physicians should avoid the temptation to increase the sprint length too rapidly, as this often hinders the progress of weaning. Initially, sprinting should be performed only during wakefulness, as ventilatory muscle function and central respiratory drive are more intact during this period than during sleep. Usually a child is weaned off the ventilator completely during wakefulness, before attempting to reduce sleeping ventilatory support. It is important to remember that sprint weaning requires that the child receives complete ventilatory support during rests (27). Because sprint weaning simulates athletic training, better success has been observed with this form of ventilator weaning in prolonged respiratory failure when ventilatory muscle fatigue is thought to be a component. In effect, this technique raises the fatigue threshold, so that a child can perform an increased level of work of breathing, and sustain adequate spontaneous ventilation (26) (Fig. 50.4).

can be expected to develop CRF (30,31,32). The most obvious example is the child with a progressive neuromuscular disorder, such as spinal muscular atrophy or muscular dystrophy (33,34). Discussion begins long enough before the anticipated need to allow the child and family to thoroughly evaluate the options, discuss their feelings, and reach a decision. Families need to be informed that a home ventilator is not a guarantee that the child will survive. We found that children receiving HMV via tracheostomy face a 20% mortality rate in the first 5 years after discharge home (13). If the family opts for chronic ventilatory support, then noninvasive ventilatory support is usually initiated first, or a tracheostomy is performed and positive-pressure ventilation (PPV) is started electively before the patient develops major complications of CRF (27,33,34,35). Since hypoventilation is more severe during sleep than during wakefulness, nocturnal assisted ventilation often prevents the development of pulmonary hypertension and other complications of chronic intermittent hypoxia (35). Nocturnal ventilation allows ventilatory muscle rest and improves endurance for spontaneous breathing while awake; therefore, it is actually associated with an enhanced quality of life (27,35). Further, with this approach, the child and family do have the opportunity to make a truly informed decision about whether or not to initiate chronic ventilatory support (30,32). Preemptive initiation of assisted ventilation prior to sleep related alveolar hypoventilation has not been shown to be helpful in Duchene muscular dystrophy, and is not indicated.

TABLE 50.1 APPROACHES TO WEANING CHILDREN WITH PROLONGED RESPIRATORY FAILURE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Children with CRF and relatively stable ventilator settings are candidates for HMV (15,16,17,36

Children with CRF and relatively stable ventilator settings are candidates for HMV (15,16,17,36

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree