Table 2.1 Pain medications | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adjuvant therapies are most commonly used to treat neuropathic pain and chronic headache.

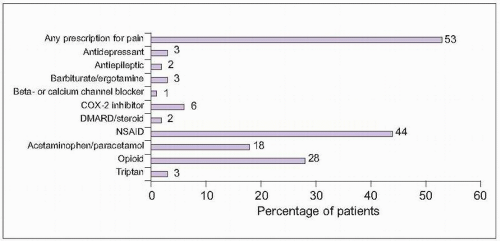

2.1 Common prescription medications for chronic pain. Among people with moderate or severe chronic pain in Europe and Israel, 53% reported currently using a prescription medication for pain. The most commonly used medication group was nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Some of the reported medications would be used for specific pain conditions, like beta- and calcium channel blockers or triptans for chronic headache and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) for rheumatoid arthritis. (Based on Breivik H, et al., 20061.) |

noradrenergic pathways from the locus ceruleus dampen pain transmission by inhibiting pain pathways in the spinal cord, through interactions on inhibitory interneurons.

Table 2.2 Number-needed-to-treat (NNT) for efficacy of pain medications | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 2.3 Mechanisms of pain medications | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

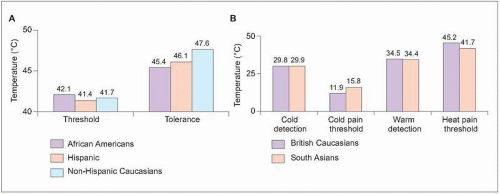

tolerance and greater perception of pain stimuli as unpleasant in African Americans and Hispanics compared with Caucasians (2.5)5,6,7,8. Reduced pain tolerance to experimental pain in African Americans supports findings in a population of chronic pain patients that showed similar pain intensity but increased perception of pain unpleasantness in African Americans compared with Caucasians9. Asians similarly demonstrate increased sensitivity to pain10.

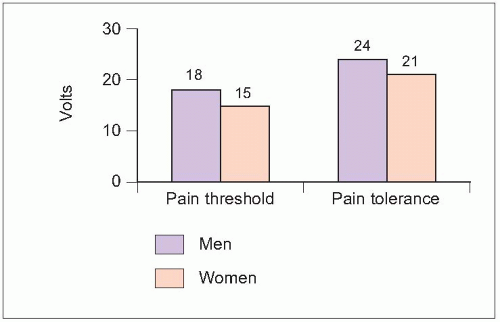

2.3 Pain sensitivity by gender. The ability to perceive electrical stimulation as pain (threshold) and greatest tolerable level (tolerance) were tested in 20 healthy adults. Both pain threshold and tolerance were significantly higher in men (P<0.05). (Based on Walker JS, Carmody JJ, 19983.) |

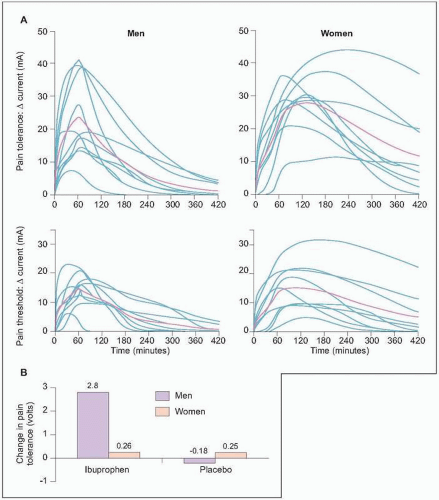

2.4 Analgesic response by gender. A: The effect of a single dose of intravenous morphine was tested in healthy adults (10 males and 10 females). The graphs show individual (blue lines) and mean (red lines) responses to electrical current stimulation. Baseline currents were similar between genders for pain threshold and tolerance. While concentrations of morphine and its metabolites were similar between genders, women demonstrated greater overall morphine potency, slower speed of analgesic onset, and longer duration of analgesic effect. These data support clinical observations of higher opioid use in males for acute pain than females. (Based on Sarton E, et al., 20004.) B: Twenty healthy adults (10 males and 10 females) were similarly treated with ibuprofen or placebo and tested with electrical stimulation. Neither ibuprofen nor placebo affected pain threshold, while ibuprofen did affect pain tolerance. Pain tolerance was significantly increased with ibuprofen in men (P<0.05) and not different between ibuprofen and placebo in women. (Based on Walker JS, Carmody JJ, 19983.) |

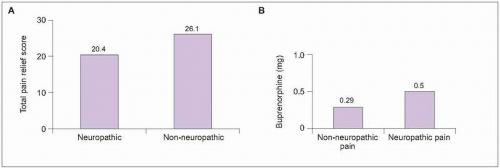

however, demonstrate medication misuse or abuse, including reporting lost/stolen prescriptions, obtaining opioids from secondary sources, and repeatedly requesting early refills12. While opioids are most effective in reducing non-neuropathic pain, they may also be used for disabling neuropathic pain, although pain reduction may be less and dose requirements may be higher (2.7)13,14.

2.5 Differences in pain response by race. A: Experimental pain testing was completed in healthy adults representing three ethnic groups: African American (N=63), Hispanic Americans (N=61), and non-Hispanic Caucasian Americans (N=82). Demographic factors were considered as covariates in analyses. There were no differences in pain threshold for heat or cold pain among genders (not shown). Both heat and cold pain tolerance, however, were similar for African Americans and Hispanics and significantly lower in both ethnic groups compared with non-Hispanic Caucasians (P<0.05). (Based on Rahim-Williams FB, et al., 20078.) B: In a similar study, pain testing was performed in 40 healthy adults: 20 British Caucasians and 20 South Asians from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Perception of cold and warm was similar between ethnicities, while pain thresholds were lower among Asians. Differences between Caucasians and Asians were significant for heat pain threshold (P=0.006) and showed a trend toward significance for cold pain threshold (P=0.057). (Based on Watson PJ, et al., 200510.) |

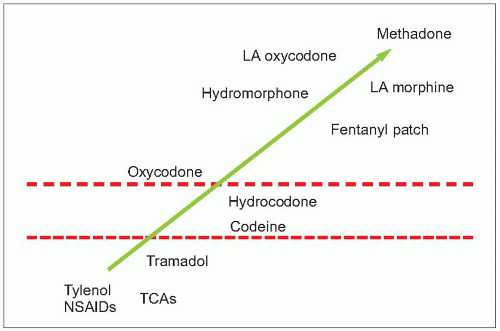

2.6 Analgesic potency ladder. This analgesic potency ladder is based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 3-step analgesic ladder. The WHO recommends matching analgesic potency with pain severity. Patients with mild pain are initially treated with therapies within the first rung of the ladder, including nonopioid analgesics and adjuvant therapy. Treatment for patients with moderate severity pain should include the addition of weak opioids, with strong opioids reserved for patients with severe pain. The effectiveness of this approach was validated in a 10-year prospective study with cancer pain patients. Although 3 in 4 patients required weak or strong opioids, pain relief was shown to be equally effective in each step of the ladder when therapy was initiated with analgesic potency matched to pain severity. LA: long-acting; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant. |

2.7 Opioid efficacy for neuropathic pain. Opioids may be effectively used to reduce neuropathic pain. Total pain relief was evaluated in 4 single-dose studies in which 168 patients received doses of opioid (A). Pain relief occurred with both groups, although relief was significantly better in patients with non-neuropathic pain (P=0.02). (Based on Cherny NI, et al., 199413.) In a second study (B), the dosage of opioid buprenorphine necessary to reduce pain by at least 50% was compared in 21 patients who were treated for non-neuropathic postoperative thoracic surgery pain and 1 month later for post-thoracotomy neuropathic pain. While pain reduction was successfully achieved for both acute non-neuropathic pain and subsequent neuropathic pain, the opioid dosage required to achieve similar pain relief was significantly higher for the neuropathic pain (P<0.001). (Based on Benedetti F, et al., 199814.) |

Table 2.4 Analgesic effects from antidepressants | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

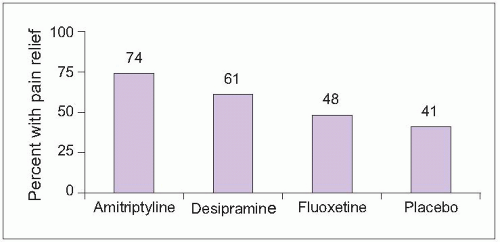

2.8 Effects of antidepressants on diabetic neuropathy pain. Fifty-seven patients (59% male; median age = 58 years) with painful diabetic neuropathy were randomized to treatment with amitriptyline, despiramine, fluoxetine, or placebo in two double-blind studies. Mean daily doses were 105 mg amitriptyline, 111 mg despiramine, and 40 mg fluoxetine. The graph shows the percentage of patients receiving each treatment who experienced moderate or better pain relief. Pain relief was superior to placebo for both tricyclic antidepressants (P<0.05) but not fluoxetine. There were no significant differences in efficacy between the two tricyclics. (Based on Max MB, et al., 199216.) |

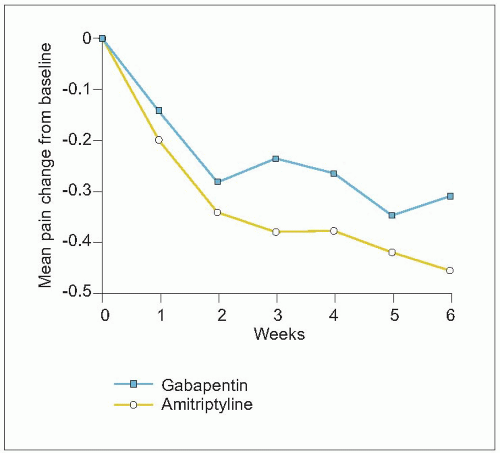

2.9 Antiepileptics for neuropathic pain. In a controlled, pilot study, 25 patients with diabetic neuropathy were randomized to treatment with gabapentin (mean dosage = 1,565 mg daily) or amitriptyline (mean dosage = 59 mg daily). At least moderate pain relief was experienced by 52% with gabapentin and 67% with amitriptyline. The graph shows changes in pain severity from baseline for patients completing the full 6 weeks of treatment. A reduction of 0.35 represents a decrease from moderate to mild pain. There were no significant differences in pain reduction between gabapentin and amitriptyline. These data support that both tricyclic antidepressants and antiepileptics can be effective therapies for neuropathic pain. (Based on Morello CM, et al., 199917.) |

growth plate, it should be discontinued as pregnancy progresses. Opioids are best limited to infrequent, intermittent use. Patients who have been chronically using daily opioids during mid-to-late pregnancy must continue daily opioids because of the risks of fetal mortality and premature labour associated with intrauterine fetal opioid withdrawal19.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree