Introduction

Musculoskeletal pain is ubiquitous – everyone gets it. There are three main causes:

Everyone is familiar with the aches and pains that generally follow unaccustomed activity and most of us will have had at least one episode of acute post-traumatic pain affecting our muscles, bones or joints. These problems are generally short lasting and not very bothersome. However, huge numbers of us, particularly older adults, also experience chronic, intrusive musculoskeletal pain. Recent surveys suggest that 30–50% of older adults suffer chronic pain, most of which comes from the musculoskeletal system. The spine is the commonest site involved (Back pain is dealt with in Chapter 5) followed by the knees, shoulders and feet. A disease is not always apparent, but of the chronic musculoskeletal disorders that cause chronic pain osteoarthritis is by far the most common.

Although some diseases, such as gout, are renowned for the severe acute, self-limiting pain that they can cause, this chapter only covers chronic musculoskeletal pain and disease.

The Anatomy and Physiology of Musculoskeletal Pain

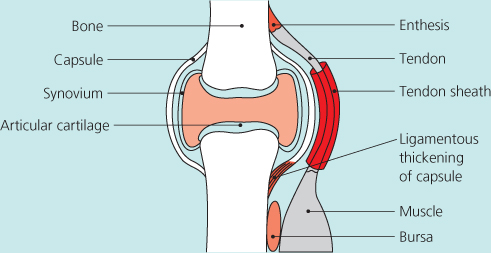

Figure 4.1 shows a diagrammatic representation of a synovial joint and its surrounding structures. The articular cartilage is aneural, but the other structures are all richly innervated, with particularly dense sensory innervation seen at the insertions of tendons or ligaments into bone (the entheses), the subchondral bone and the periosteal covering of bones. Nocioceptive systems seen in these structures include the A-delta fibres responsible for acute sharp pain, and the C fibres responsible for chronic dull, throbbing pains (Chapter 2). Sensory input from these structures is an essential part of our function – as we stand or walk the entheses are ‘sensing’ the strain arising from the different muscles and joints, and through spinal pathways adjusting muscle tone accordingly, without our being aware of anything. Normally, these everyday activities, including more strenuous things such as running, do not excite the pain systems, but it now appears that in joint disease, particularly if inflammation is present, the system can become sensitised such that normal everyday activities become painful. In addition, pain sensitisation can occur at the spinal level, and cortical activity can lead to disinhibition of musculoskeletal pain.

Figure 4.1 Cross-section of a synovial joint and surrounding tissues marking the most richly innervated structures.

The Experience of Musculoskeletal Pain

Healthcare professionals and academics carrying out research on musculoskeletal pain have focused their attention almost entirely on the severity of musculoskeletal pain, with some additional emphasis on whether it occurs at night or not. So, the ‘patient’ is asked how bad the pain is and whether it wakes them at night or not, and management strategies are suggested accordingly. However, it is clear that those with chronic musculoskeletal pain can experience a rich and varied set of symptoms not adequately described by enquiries about pain severity. It is now known, for example, that people with osteoarthritis usually experience two quite different sorts of pain – their ‘usual’ activity-related dull ache, and unpredictable attacks of severe, short lasting, more bothersome pain; and people with inflammatory rheumatic diseases experience severe morning stiffness in joints, which may be their overriding symptom.

Nearly everyone with chronic musculoskeletal pain, be it back pain, fibromyalgia or due to osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, also experiences four other associated problems:

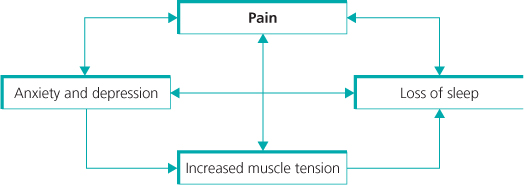

The interactions between sleep problems, fatigue, anxiety/depression and pain are complex and not fully understood. The interactions can work in both directions (pain causing depression and depression increasing pain for example), and it is clear that some people can get into a ‘viscious circle’ in which loss of sleep, fatigue and anxiety or depression increase the amount of pain experienced, with the pain also causing sleep and mood problems (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 People with chronic pain often get into a ‘viscious circle’ of problems. The pain leads to anxiety and depression, which can make the pain worse, as well as affecting sleep. Lack of sleep also increases pain. Muscle tension is increased by pain, and can also lead to more pain as well as contributing to further loss of sleep, anxiety and depression.

A Classification of Musculoskeletal Disease and Pain

The WHO classification of musculoskeletal disorders breaks them into five groups, which, in rough order of frequency in the population, are shown in Figure 4.3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree