Childhood Migraine and Related Syndromes

Ishaq Abu-Arefeh

Eric Pearlman

MIGRAINE WITHOUT AURA

Migraine without aurua (MO) in children and adolescents has some features that make it different from that in adults (Chapter 43). The duration of attacks is variable, lasting from 1 to 72 hours; the pulsating quality of pain is not easily described by young children; and headache is, commonly, at the forehead. The headache, as in adults, is moderate or severe in intensity, aggravated by routine physical activity, and associated with nausea and/or vomiting and/or photophobia and phonophobia.

Epidemiology

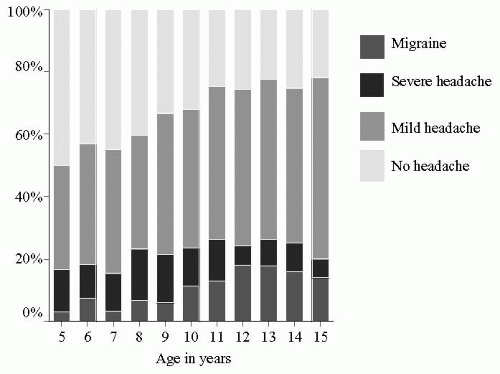

The prevalence of migraine increases with age, from 0 to 7% in preschool children (under 7 years) to 20% in adolescents (Fig. 130-1), with 75 to 80% being MO (20). The peak age of onset is 12 to 14 years. In younger children, migraine is more common in boys than girls, but is more common in girls after the age of 12 years (2).

Clinical Features

During attacks of migraine the child is pale and quiet and wants to be left alone. Commonly associated symptoms are loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and intolerance to light, noise, smell, and physical activities. Dizziness (unreal sensation of movement), abdominal pain, and limb pain may also be present. Short attacks of migraine lasting less than 2 hours are uncommon, but are well recognized as confirmed by prospective diary records (1). The International Headache Society (IHS) criteria for the diagnosis of MO (16) are otherwise as described in earlier chapters.

MIGRAINE WITH AURA

Migraine with aura (MA) in children and adolescents is characterized by distinct and sometimes graphic symptoms that precede the onset of headache. Children describe the symptoms, commonly visual, in words and by drawings (23). Common visual aura includes blurred vision, tunnel vision, blind spots (scotomata), zigzag colored lines in front of the eyes, or image distortion. Less commonly, the aura symptoms are sensory such as tingling sensation or numbness. Motor symptoms are rare and may represent a complicated migraine attack or hemiplegic migraine. The aura is brief and fully reversible. Headache follows within 60 minutes from resolution of aura, but the two phases can be indistinct. The aura symptoms can be intense and frightening to the child and parents, leading to their urgently seeking medical advice. The headache phase is similar to that in MO, but occasionally atypical.

Prognosis of Childhood Migraine

The natural course of migraine is that of remissions and relapses. Remissions of at least 1 year were recorded in up to 58% of patients during periods of follow-up of at least 5 years (19). Long-term follow-up of 73 children showed that 34% became headache free after 6 years, 62% after 16 years, and only 40 to 47% after 22 to 40 years (7,8).

Management of Childhood Migraine

A management plan should follow a careful assessment and accurate diagnosis to alleviate concerns of the child and anxieties of the parents. The treatment starts with reassurance and education of the child and parents about the benign nature of migraine and its remitting-relapsing

course. Diagnostic studies, including neuroimaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) is necessary in a small number of patients with features of secondary headaches.

course. Diagnostic studies, including neuroimaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) is necessary in a small number of patients with features of secondary headaches.

Management of Acute Attacks

Many children and families may try nonpharmacologic strategies (rest and sleep) and over-the-counter analgesics before they consult their doctors, but only one in three parents can determine and measure the correct doses for children (21). Medications are likely to be successful if given soon after the onset of attack in appropriate dosages.

In children and adolescents under 15 years of age, paracetamol (acetaminophen) (15 mg/kg body weight, maximum 1g) and ibuprofen (10 mg/kg) are effective and safe (15).

Aspirin is effective, but its association with Reye syndrome prohibits its use in children under 15 years. No clinical trials are available on other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Occasionally, codeine phosphate may be necessary if other acute treatments fail.

Sumatriptan (Imigran/Imitrex) is a selective agonist of 5-HT1B-D receptors with a good efficacy and safety record in adolescents. It is available as a subcutaneous autoinjection, oral tablets, and a nasal spray. Multicenter, randomized controlled trials of nasal sumatriptan in doses of 10 and 20 mg showed good efficacy and safety profile as compared to placebo (6,27). Nasal sumatriptan is now licensed for use in 12- to 17-year-olds in some countries. Other triptans are also available, but their efficacy in children and adolescents is not established yet.

Metoclopramide (Maxolon/Reglan) or prochlorperazine (Stemetil/Compazine) may alleviate nausea and vomiting but should be used with caution due to possible extrapyramidal symptoms and dystonic reactions.

Prevention

Nonpharmacologic strategies for the prevention of migraine include the avoidance of identified trigger factors and adopting a healthy lifestyle, including a predictable sleep pattern, regular meals, and regular pattern of rest and exercise.

There is limited evidence for the efficacy and tolerability of pharmacologic prophylaxis. It is only indicated if acute treatment is unsuccessful and migraine attacks are frequent (more than two attacks per month), prolonged, or severe enough to interfere with normal life.

Propranolol reduced the frequency of migraine attacks in one trial (18), but not in another (13). In children over 7 years of age, propranolol may be given in a dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg/day in two divided doses (maximum 40 to 50 mg twice daily). Pizotifen (Sanomigran), commonly used in the United Kingdom, may be effective in the prophylaxis of abdominal migraine (24), but not in migraine headache (14). Valproate is effective in adults, but has not been studied in children (9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree