Chapter 33 Childhood emergencies

The child in the emergency department presents a challenge to the busy emergency physician, particularly in a setting where both adults and children are being treated and the general culture is not a paediatric one. Children are different in that they are dependent, developing and growing rapidly (see Table 33.1). They also differ in their spectrum of disease and response to illness.

Table 33.1 Normal respiratory rate and cardiovascular values

| Age | Normal respiratory values (breaths/min)∗ | Normal cardiovascular values (beats/min)∗∗ |

|---|---|---|

| Infants | 40 | 160 |

| Preschool | 30 | 140 |

| School age | 20 | 120 |

∗ Endotracheal tube size = (age in years ÷ 4) + 4

∗∗ Blood volume = 80 mL/kg; systolic blood pressure = 80 mmHg + (age in years x 2)

RESUSCITATION

In the emergency situation, a child’s condition can deteriorate very rapidly. This is due to:

There may also be a greater risk of acute deterioration in the following cases:

Respiratory

Increased breathing effort is a sign of increasing respiratory insufficiency and is characterised by: tachypnoea, use of accessory muscles, expiratory grunting, stridor, wheezing, nasal flare, dyspnoea and cyanosis. Other important but often forgotten signs of impending respiratory embarrassment in children are exhaustion and apnoea.

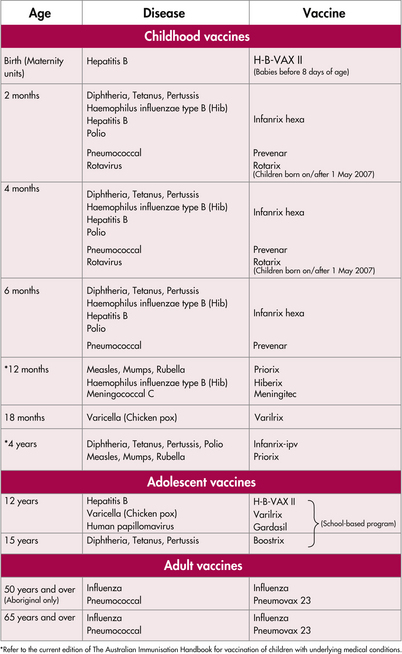

Table 33.2 NSW Immunisation schedule from 1 July 2007

|

CNS

AIRWAY EMERGENCIES

Croup

Croup is viral laryngotracheobronchitis characterised by a barking cough. Often several days of upper respiratory tract symptoms precede the cough. The associated respiratory distress is worse at night and with anxiety in child or parent. Spasmodic croup occurs without accompanying infective symptoms and is often recurrent. Stridor at rest is an indication of severity, while cyanosis is a pre-arrest state. Lateral airways X-rays are not needed and are dangerous as the child is unstable.

A calming environment with the child on the mother’s lap is therapeutic.

Foreign body inhalation

This causes an acute onset of respiratory distress, often in a child between 6 months and 2 years. If the object is in the upper airway, complete or partial obstruction may be present. If the child is moving air or coughing, removal under inhalational anaesthetic by skilled personnel is advisable. If the airway is completely obstructed, rapid back blows in an infant or the Heimlich manoeuvre in an older child should be performed. Direct visualisation and removal of the object with Magill’s forceps may be possible. If this is not successful, a needle cricothyroidotomy should be performed. Cricothyroidotomy using a scalpel is not recommended for children under 5 years.

RESPIRATORY EMERGENCIES

Pneumonia

Organisms causing pneumonia include:

THE UNCONSCIOUS CHILD

Always examine the whole child in the light of a thorough history.

Immediately

THE FEBRILE CHILD

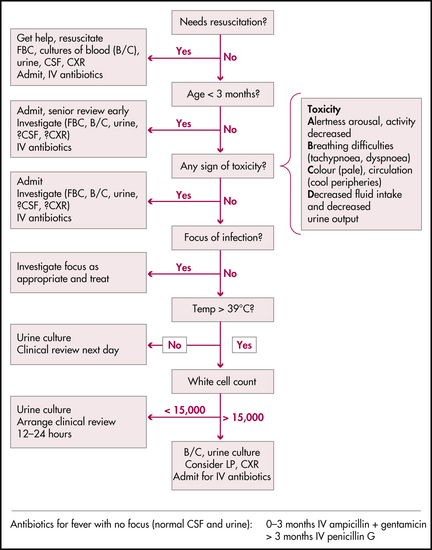

If the cause is still not evident consider intussusception (may have a ‘cerebral’ presentation). Fever is one of the most common causes of presentation to an emergency department. Most fevers are due to viral infections, but care must be taken to exclude a bacterial infection. Diagnosis can often be difficult, particularly in the younger child where caution is advised. The child without a clear focus presents a real challenge, with pneumococcal and meningococcal infections being the most common infective condition encountered. Various approaches are advised in the literature, ranging from cautious assessment and observation through to aggressive management (see Figure 33.1).

Figure 33.1 Flowchart for an infant with fever

NSW Health, Acute management of infants with fever. Assessment and management: flowchart for child < 3 years old with fever (> 38°C) axillary, p 4

Factors to consider when assessing a febrile child: