Child Abuse/Assault

Richard Lichenstein

Adrienne H. Suggs

Child maltreatment is an unfortunate aspect of clinical forensic medicine. Caffey (1) first described child abuse in 1946, when he recognized that some patients with long-bone fractures also had subdural hematomas. Kempe et al. (2) elaborated and coined the term “battered-child syndrome” in 1962. Since then, health care professionals have become increasingly aware of child abuse and its manifestations, and laws have been enacted that mandate reporting of suspected child abuse by health care professionals, educators, and human service workers.

Although definitions vary by state, physical child abuse is usually defined as the physical injury of a child by a parent, a household or family member, or another person who has permanent or temporary custody or responsibility for supervision of that child. Other forms of child maltreatment include neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse.

The National Clearinghouse on Child Abuse and Neglect Information statistics for 2003, document an estimated 2.9 million referrals to child protective services for investigation of child maltreatment (3). Of these, more than two-thirds were accepted for investigation, and approximately 30% were substantiated, translating to a victimization rate of 12.4 per 1,000 children. Of substantiated cases, more than 60% (63.2%) suffered neglect, and almost one fifth (18.9%) suffered physical abuse. Approximately 10% were victims of sexual abuse, 5% suffered psychological or emotional abuse, and 2.3% suffered medical neglect. Seventeen percent were victims of more than one type of abuse. An estimated 1,500 children died of abuse and neglect, translating to a fatality rate of 2 per 100,000 children in the general population.

Victimization rates continue to be the highest for the youngest children (0–3 years of age), at 16.4 per 1,000 children nationally, and decline with increasing age. Girls are slightly more likely to be victims than boys. Pacific Islanders, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and African Americans have the highest victimization rates at 21.4, 21.3, and 20.4 per 1,000 children, respectively. These rates are almost twice those of whites and Hispanics, at 11.0 and 9.9 per 1,000 children (3).

Although perpetrators of child maltreatment tend to be female, perpetrators of physical and sexual abuse tend to be male. Most perpetrators of child maltreatment are parents (84%) or other relatives (6%). Fewer than 1% are day-care providers or facility staff. However, when looking at sexual abuse alone, nearly 76% of perpetrators are friends or neighbors, 30% are other relatives, and <3% are parents (3).

Pediatricians and emergency department physicians must maintain a high level of suspicion when children present with injuries highly specific for abuse or when children have injuries not consistent with the history provided. The physician must be aware of the many risk factors for abuse and must be able to identify clues in the history that raise the suspicion for abuse. More than half of the physical

abuse cases have no physical manifestations (4). Factors that increase the likelihood of being a victim of physical abuse and neglect include prematurity, chronic illness, mental retardation, and difficult temperament. Caretaker and environmental risk factors include young parents, abuse of the caretaker as a child, previous removal of a child by protective services, substance abuse, mental illness, lack of family support, and low socioeconomic status (3, 4, 5, 6). Clues that suggest abuse include an account not consistent with the injury or the developmental age of the child, changing or inconsistent histories, a history of abuse, delay in seeking treatment, projection of blame onto a third-party (such as a sibling), and aggressiveness of the caretaker (3, 4, 5, 6).

abuse cases have no physical manifestations (4). Factors that increase the likelihood of being a victim of physical abuse and neglect include prematurity, chronic illness, mental retardation, and difficult temperament. Caretaker and environmental risk factors include young parents, abuse of the caretaker as a child, previous removal of a child by protective services, substance abuse, mental illness, lack of family support, and low socioeconomic status (3, 4, 5, 6). Clues that suggest abuse include an account not consistent with the injury or the developmental age of the child, changing or inconsistent histories, a history of abuse, delay in seeking treatment, projection of blame onto a third-party (such as a sibling), and aggressiveness of the caretaker (3, 4, 5, 6).

Physicians must maintain a high degree of suspicion if the history suggests physical abuse, and caretakers who do not fit the profile should not fool them. For example, Jenny et al. reported that young age of the child, white race, less severe symptoms, and an “intact” family were key features that led to missed diagnoses of abusive head trauma (AHT) (see subsequent text) (7).

Head Trauma/Central Nervous System Injury

Inflicted head trauma constitutes the leading cause of nonaccidental death associated with child abuse (8, 9). When caregivers provide a history that is inadequate to explain the extent of head injury, child abuse must be considered. In a population-based study, Keenan et al. documented an incidence of traumatic brain injury among children younger than 2 as 17 per 100,000 (95% CI, 13–21 per 100,000 year); the incidence was seven times greater for children younger than 1 year of life (10). Perpetrators of nonaccidental head trauma are usually male (in decreasing frequency: father, stepfather, and mother’s boyfriend). Mothers and female baby-sitters have also been implicated (11, 12). Risk factors for AHT are similar to those for child abuse in general. The child may be premature or have a difficult temperament or chronic illness (6). The family may have the stressors of poverty, drug abuse, parental depression, low education level, or other males (stepfathers and boyfriends) living in the home (13).

Shaken baby syndrome (SBS) is classically described as occurring in infants younger than 6 months, with minimal or no external signs of trauma, subdural hematomas, and retinal hemorrhages (6). It usually presents as a spectrum of findings, including intracranial, cervical cord, intraocular, skeletal, and cutaneous injuries. Caretakers may be unaware of the specific injuries that can be caused by shaking, but it is reported that the act of shaking or slamming can be so violent that competent individuals observing the shaking would recognize it as dangerous (14). SBS has also been called shaken impact syndrome, based on the combination of autopsy findings in infants who were fatally abused and of biomechanical studies not performed on humans. The study concluded that severe head injuries require impact, not shaking alone (15). However, most authors claim that impact is not needed. Most also agree that inflicted head trauma encompasses a constellation of findings, with or without impact (6), thereby producing the general terms of nonaccidental head trauma, inflicted head trauma, or AHT.

It is important to distinguish between accidental and inflicted head injuries. Most short vertical falls in infants, usually less than 4 feet (most childhood falls), result in minor injury or no injury at all. Although falls from low heights may cause linear, unilateral skull fractures without intracranial injury, significant force is required to sustain depressed, stellate, complex, bilateral, or basilar skull fractures. Other than the rare reported cases of epidural hemorrhage, falls from low heights do not cause significant intracranial pathology, including subdural or subarachnoid hemorrhage, or retinal hemorrhage (15, 16, 17, 18). Child abuse must be considered in children with intracranial injuries but without a history of motor vehicle trauma, falls from heights greater than 4 feet, or head impact from a moving object.

In AHT there may be an absence of external findings to implicate nonaccidental trauma (19). The degree of injury depends on the force or severity of the shake or impact and the time elapsed from the event. Symptoms may be vague and occur intermittently, which may be misleading to evaluating physicians (20). The range of manifestations includes poor feeding, vomiting, lethargy, irritability, colic, apnea, seizures, and death (6). Children in one study were seen and diagnosed by physicians with other conditions 2.8 times before being diagnosed with inflicted head injury (7).

Intracranial pathology encountered in AHT includes, most commonly, subdural hemorrhages along with parenchymal injuries, including diffuse axonal injury (DAI). During shaking, because the infant’s head is heavy and the neck muscles are weak, intracranial bleeding results from a tearing of cortical bridging veins, which stretch and shear as the head is subjected to rotational forces. These same inertial forces and rotational acceleration forces also permit tearing of axons in the child’s incompletely myelinated brain, resulting in DAI, contusions, parenchymal tears, and cerebral edema (21). Other intracranial pathology includes subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral contusions. Contusions and lacerations are proportional to the contact forces applied. Skull fractures are seen in these cases but can also be seen with unintentional trauma. In general,

because there may be similarities in the types of skull fractures in unintentional and intentional injury, abuse should be suspected if the injury does not correlate with the history and the physical examination findings. Multiple bilateral skull fractures should be reviewed carefully as to a possible abusive source but may be explained by some types of unintentional injury (22). Parenchymal injury is also seen secondary to hypoxia and ischemia (23). The incidence of epidural hematoma is low (6, 7, 8). On the basis of a study of head-injured children younger than 3 years of age, Wells et al. (24) reported that 78% of epidural hemorrhages were felt to be unintentional compared with 18% associated with abuse.

because there may be similarities in the types of skull fractures in unintentional and intentional injury, abuse should be suspected if the injury does not correlate with the history and the physical examination findings. Multiple bilateral skull fractures should be reviewed carefully as to a possible abusive source but may be explained by some types of unintentional injury (22). Parenchymal injury is also seen secondary to hypoxia and ischemia (23). The incidence of epidural hematoma is low (6, 7, 8). On the basis of a study of head-injured children younger than 3 years of age, Wells et al. (24) reported that 78% of epidural hemorrhages were felt to be unintentional compared with 18% associated with abuse.

Shaken infants are also at risk for cervical cord injury because of the infant’s large head-to-torso ratio and weak neck musculature. Spinal cord contusions and subdural and epidural hematomas at the cervicomedullary junction may lead to morbidity and mortality (6).

Retinal hemorrhages are associated with extraordinary force and are rare occurrences in minor unintentional trauma (25, 26, 27). Unilateral or bilateral retinal hemorrhages are present in 75% to 95% of cases of AHT (20). Retinal hemorrhages do occur with unintentional trauma, birth trauma, bleeding disorders, and glutaric aciduria type I, for example, but diffuse and severe retinal hemorrhages are considered specific for AHT. In AHT, retinal hemorrhages usually involve the multiple layers of the retina and extend outside the posterior pole to the periphery and oro serrata, to the periphery of the retina (28). Retinal folds or detachment may also develop (5). In children with birth trauma, retinal hemorrhages may be seen (in approximately 30% of newborns), but they resolve by the age of 4 weeks (6). Retinal hemorrhage after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has been reported (rarely), but not in the absence of previous head trauma or abnormal coagulation and platelet studies. When such hemorrhage is found, it tends to be morphologically different from that associated with AHT (29, 30).

The interval between head injury and symptom onset may help identify a perpetrator. Determining whether a lucid interval has occurred can be difficult because perpetrators may not be telling the truth (31). Gilliland found that neurologic changes and severe symptoms, such as difficult breathing, unresponsiveness, and respiratory collapse, occurred less than 24 hours after head injury in most of the incidents. Of note, whenever information was supplied by someone other than the perpetrator, the child was not described as normal during the period (32). Starling et al., studying perpetrators, found that 97% of convicted perpetrators who admitted to inflicting head trauma were with the child at the time of onset of symptoms, suggesting that symptoms occur soon after the abuse, as opposed to emerging over hours or days (11). In a more recent study of perpetrator admissions, perpetrators said symptoms appeared immediately after the abuse (33). In a retrospective review of 95 unintentional fatalities involving head injury, only one patient, with an epidural hematoma, had a lucid interval (34).

Another controversy is the theory of rebleeding, after minor or no trauma, into chronic or subacute subdural hemorrhages. This theory has implications in identifying a perpetrator. After reviewing the literature in 1999, Block concluded that “there is no evidence to support the current concept that rebleeding of an organizing subdural hemorrhage can occur from a subsequent trivial injury and cause severe neurologic impairment or death” (29). However, there have been rare reports that led investigators to continue to examine the issue. In 2002, Hymel et al. published two case reports involving indoor, unintentional, and pediatric closed head trauma that resulted in intracranial rebleeding. Both impacts occurred in medical settings and were witnessed by medical personnel (35).

Physicians should be aware that intentional head trauma is often associated with extracranial signs of abuse, although physical findings such as cutaneous bruising may or may not be present (12). Posterior rib fractures can occur because of squeezing the infant’s chest while shaking the infant (36). Long-bone fractures may be present. In one review, 32% of the victims had long-bone fractures because of repetitive abuse (36). The physician should perform a careful search for other physical signs of abuse or neglect.

Abdominal and Thoracic Injury

Both solid and hollow organs are at risk for injury in thoracoabdominal trauma. Abdominal trauma is the second most common cause of child abuse deaths (37, 38). Although motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) are the leading cause of major abdominal trauma in children, child abuse poses a greater risk of subsequent death. In fact, compared with unintentional injuries, including MVC, the mechanism of child abuse increases the likelihood of death from traumatic abdominal injuries sixfold (39). Unfortunately, children who sustain severe abdominal trauma from child abuse often present late for medical attention (39). Generally, their presentation is in response to the pathology that results from abdominal injury rather than to the injury itself (40). Blunt abdominal trauma can result in no external evidence of injury, even if there is severe organ and tissue damage (39, 40, 41). Initial manifestations may be nonspecific and include abdominal pain and distention, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Peritonitis and associated sepsis may become evident within

hours to days after abdominal injury, whereas hematoma and subsequent intestinal obstruction usually take longer, possibly days, to diagnose. Multiple injuries are seen in 18% to 37% of children with inflicted abdominal trauma (37).

hours to days after abdominal injury, whereas hematoma and subsequent intestinal obstruction usually take longer, possibly days, to diagnose. Multiple injuries are seen in 18% to 37% of children with inflicted abdominal trauma (37).

Sometimes older children can describe the causative event. In the case of a younger child, diagnosis of abdominal trauma may rest on the history provided by the caretaker or on the suspicion of the physician. As with head trauma, the absence of any history, or the report of a minor injury despite evidence of serious trauma, should raise suspicion that the injury may have been inflicted.

Nonaccidental blunt thoracic trauma can result in rib fractures and injury to underlying structures. Lower rib fractures may lacerate the spleen or liver. Rib fractures can cause pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum. Direct blunt anterior trauma can lead to esophageal perforation, pneumomediastinum, or mediastinitis.

The spleen and the liver can sustain damage when the lower ribs are fractured. Blunt abdominal trauma may cause contusions of these organs as well. Liver injury can range from small, asymptomatic contusions to fractures that lead to significant blood loss and death. Delay in evaluation of severe liver injury increases pediatric mortality. Diagnosis of liver injury may be determined by a history of blunt abdominal trauma, abdominal pain and tenderness, elevated aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase, and computed tomography findings. Elevated liver enzymes can be helpful in evaluating occult liver injuries, even when there is no report of abdominal trauma or clinical evidence of abdominal injury (38). The spleen can be injured in both unintentional and intentional trauma scenarios, but inflicted injury should be suspected when the patient is an infant who is not yet able to walk.

In general, pancreatic injury is not common in childhood (38), but when present it may be the result of inflicted trauma. In addition to MVCs, incidents involving impact against seat belts or bicycle handlebars may damage this potentially volatile organ. Injury to the pancreas requires deep abdominal wall indentation (37). In a recent review of pancreatic trauma in children, as with abdominal trauma in general, MVC was the leading cause of pancreatic injury. Child abuse was the third most common cause of injury and the second most common cause of death in children with pancreatic injuries (42).

Injury to either or both kidneys can result from blunt thoracoabdominal trauma. The kidneys are generally well protected by the lower ribs but are not completely protected from blunt or penetrating trauma.

The abdominal viscera are also at risk of injury from blunt trauma associated with child abuse. In general, the small intestine is protected from blunt abdominal trauma, but the fixed retroperitoneal course of the duodenum renders it vulnerable (43). The duodenum is the abdominal structure most frequently injured in MVCs. The second most frequent mechanism is child abuse (44). Most children with duodenal injuries have associated trauma, including bruises, acute and healing rib fractures, and long-bone fractures. The most common form of duodenal injury from blunt trauma is intramural hematoma, resulting in partial obstruction, nausea, and vomiting. In some cases, the duodenum is ruptured and/or transected. Because delay in seeking treatment is common after abdominal trauma resulting from child abuse, peritonitis may be significant when the child is brought to the emergency department.

The ileum and jejunum are less prone to injury from blunt trauma. Ileal and jejunal injuries manifest as hematoma or perforation (37).

The colon and rectum can be injured by blunt mechanisms, usually resulting in bruising or perforation. In addition, pelvic trauma may lead to rectal injury, as can anal penetration. Substantial blunt force is required to injure these organs. Absence of plausible history and delay in seeking treatment are indicators of abuse.

Cutaneous Manifestations of Child Abuse.

Skin Lesions.

The cutaneous markings of child abuse are many, some subtler than others. Injuries involving the skin are the most prevalent injuries seen in child abuse—bruises are the most frequent type of child abuse injury reported (45). The skin is a remarkable recorder. Many types of trauma, including blunt trauma from objects and burns, produce specific injury patterns. However, as noted previously, more than half of abused children have no physical findings (4).

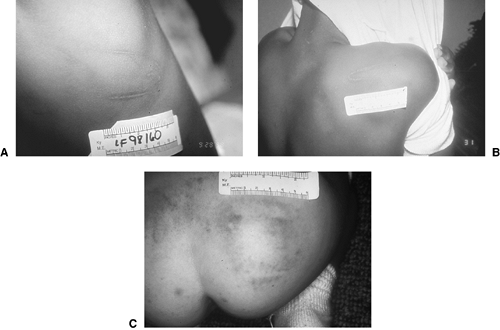

Contusions are the result of blunt trauma and, in many cases, take the shape of the instrument used to inflict them (e.g., hand-slap, belt, and loop cord) (Fig. 9.1). A hand-slap mark may consist of parallel, linear contusions with central clearing, giving the appearance of skin having been struck repeatedly with a linear, cylindrical object (Fig. 9.2). If blunt trauma is reported, it is important for the clinician to understand the nature of the contusion that can result to determine if the physical findings are consistent with the history.

Fig. 9.1. Pattern injuries A: A looped-belt injury. B: Another looped-belt injury. C: A fly-swatter injury. Note the square pattern produced from two overlapping blows through a diaper (see color plate). (Courtesy of Chief Medical Examiner’s Office, Louisville, Kentucky.) |

Fig. 9.2. Hand-slap mark. Note parallel linear contusions with central sparing that highlight the imprint of fingers (see color plate). (Courtesy of Dr. William Smock, University of Louisville School of Medicine.) |

As with fractures, a general rule is that “those who don’t cruise rarely bruise” (46). Bruises are rare in infants who do not yet “cruise” (e.g., walk by holding onto furniture) but become common among

walkers. Bruises in infants younger than 9 months who have not yet begun to walk should prompt investigation into the cause (46).

walkers. Bruises in infants younger than 9 months who have not yet begun to walk should prompt investigation into the cause (46).

Some parts of the body are prone to routine superficial traumas. In active children, the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs may sustain incidental bruises from minor, unintentional trauma. The protruding bony surfaces of the face, such as the chin, cheekbones, and forehead, are often the recipients of minor blunt trauma from falls and other accidental incidents. On the other hand, certain parts of the body are routinely “protected” during minor falls or injuries: the inner arms, submental or throat area, abdomen, lower back, and inner thighs. When cutaneous injuries in these protected areas are evident, a careful history must be taken to delineate the nature of their cause.

One frequently asked question is whether bruises can be dated to determine when they were inflicted. Accurate dating of bruises may indeed direct investigators to possible perpetrators. However, formal dating of bruises is difficult because there are many variables from patient to patient and within each patient. Many factors can determine a bruise’s appearance, including depth, location, amount of bleeding into the tissues, and the circulatory status of the bruised area (47). Depth of injury may determine how soon a bruise will appear. Superficial injuries may show skin discoloration sooner than deep injuries, which may not appear for more than 24 hours. Bruise location can affect the timing of the bruise appearance as well. Areas of the body with loose tissue (e.g., periorbital) may show bruising sooner than denser regions (e.g., bony prominences). In addition, the patient’s skin color may enhance or mask the appearance of bruises. Children with fair skin will display contusions from small impacts, whereas extensive contusions may be obscured in dark-skinned children.

Bruises show multiple color changes as they age. They are red or purple when fresh, then progress to blue, then to brown or yellow or green. Although these color changes can help distinguish “early” (recent) from “late” (older) bruises, color should not be the only determinant of a bruise’s age and implication in abuse (48).

Bruises should always be documented in the medical record to create a lasting record for future reference long after the wound has healed. The measurements of bruises can be recorded in a medical report; the bruises can be sketched and diagrammed on the report, and they can be photographed to provide prints or slides as a depiction of the injury. It must be recognized, however, that photographic representation depends on lighting and technique and may not always portray bruises accurately.

Burns.

Burning is a significant form of child abuse. Burns may be inflicted by hot liquids, flames, contact with hot objects, or caustic agents. Children’s skin is thinner than adult skin and less resistant to thermal trauma; therefore, children are burned more deeply and by less heat, and the burns often involve more body surface area and more scarring. Burning can account for 10% to 25% of child abuse injuries (49, 50, 51). Abusive burns tend to be more severe, deeper, and larger than unintentional burns (50). And abusive burns are more fatal than burns not caused by abuse (49). Distinguishing inflicted burns from unintentional burns is a critical duty of the pediatrician or emergency physician evaluating infants and children after thermal injury.

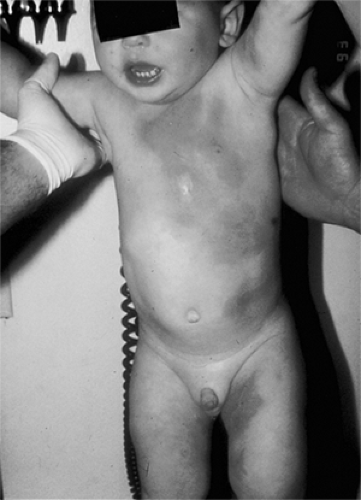

Patterns of burns from hot liquid can help determine whether the burn was unintentional or inflicted. A common unintentional scenario involves a toddler reaching up to pull a cup or a pan of hot liquid from a table edge or stove. As the hot liquid spills down over the child, it can soak through clothes, leaving a characteristic burn pattern. This scald burn pattern typically has irregular, sometimes indistinct, margins. There may be areas of both superficial and partial-thickness involvement. Satellite splash lesions may also be noted. In some cases, the burn has a typical V-shaped pattern, in which the burn diminishes distally on the child’s body, representing cooling of the liquid as it descends (50) (Fig. 9.3.

Fig. 9.3. A V-shaped scald burn caused by hot liquid cooling as it poured down this child’s body. This scald caused both first- and second-degree burns (see color plate). (Courtesy of Chief Medical Examiner’s Office, Louisville, Kentucky.) |

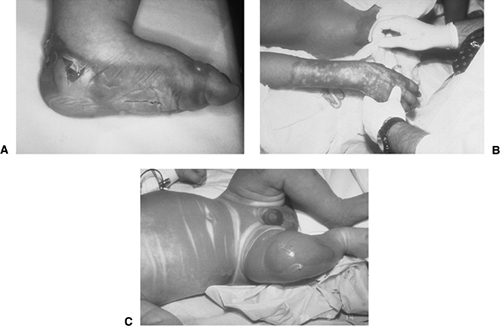

An inflicted burn from hot liquid may be the result of scalding Scald burn pattern or immersion. Typically, scald burns in abuse involve simultaneous burns of both lower extremities and of the buttocks or perineal areas (52). With immersion burns, children’s buttocks or limbs are dipped into hot water. When burns have a stocking- or glovelike Glove-like pattern, of burns (circumferential) pattern or bilateral/mirror image distribution, abuse must be considered. Features of immersion burns include distinctly clear margins between burned tissue and intact skin (50), a uniform degree of burn (e.g., second-degree) throughout the wound, and a circumferential distribution. Satellite splash marks are generally absent, and areas of skin pressed against the tub or the container of liquid, as well as skin folds, are spared (50) (Fig. 9.4). Hot tap water can cause severe scald burns, especially if the water heater setting is excessively high (53). For example, water at 111°F requires 6 hours to produce thermal skin injury, whereas water at 130°F requires only 10 seconds to cause second- and third-degree scald burns. At 140°F, the burn can occur after 1 second (50, 51).

Fig. 9.4. Immersion burns. A: Immersion or “dunk” burn caused by dipping foot in hot liquid. Note the clear delineation of burned and normal skin along with the uniform degree of burn (here a second-degree burn) throughout the burn distribution. B: Immersion burn caused by dipping infant in hot liquid. C: Note where skin folds protect underlying tissue from serious burn (see color plate). (Courtesy of Dr. William Smock, University of Louisville School of Medicine.) |

Contact with hot objects (e.g., curling irons, cigarettes, or chemicals) can also result in thermal injury. Specific hot objects making contact with skin produce pattern burns. Differentiation between unintentional and inflicted burns may depend on reconstruction of the event based on the child’s story, the caretaker’s story, and the pattern itself. Generally, inflicted burns result when rigid objects hot enough to produce at least a second-degree burn are pressed against the skin (50). The burn degree is usually uniform throughout the wound. Unintentional burns may have variability in appearance, resulting from the victim’s pulling away from the hot object.

Single burns from steam irons or curling irons must be evaluated carefully in relation to burn

location (e.g., buttocks or perineum), the age of the burn, the age of the child, and the history given (53, 54, 55). Cigarette burns (that typically measure 8mm in diameter) should spark the investigator’s curiosity because lit cigarettes are not common childhood hazards (55, 56).

location (e.g., buttocks or perineum), the age of the burn, the age of the child, and the history given (53, 54, 55). Cigarette burns (that typically measure 8mm in diameter) should spark the investigator’s curiosity because lit cigarettes are not common childhood hazards (55, 56).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree