FIGURE 7.1 Carotid plaque. (Courtesy of Dr. Ed. Uthman, MD)

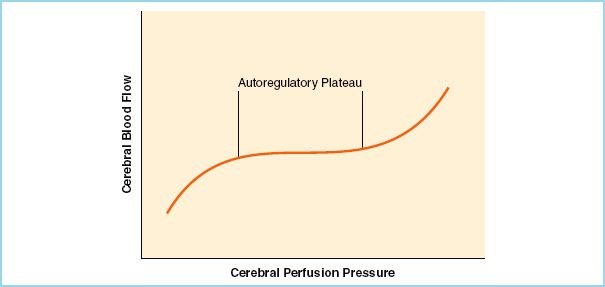

FIGURE 7.2 Cerebral autoregulation. (Reused from Kincaid MS, Lam AM. Anesthesia for neurosurgery. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Stock MC, eds. Clinical Anesthesia. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:1008, with permission.)

FIGURE 7.3 Circle of Willis. (Reused from Kincaid MS, Lam AM. Anesthesia for neurosurgery. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Stock MC, eds. Clinical Anesthesia. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:1006, with permission.)

B. Risk factors [12]. These are the very risk factors for atherosclerosis and include the following:

1. Hypertension (HTN)

2. Cigarette smoking

3. Hyperlipidemia

4. Diabetes mellitus (risk of stroke almost 2.5 times)

5. Excessive alcohol intake (>6 drinks daily)

6. Elevated homocysteine levels

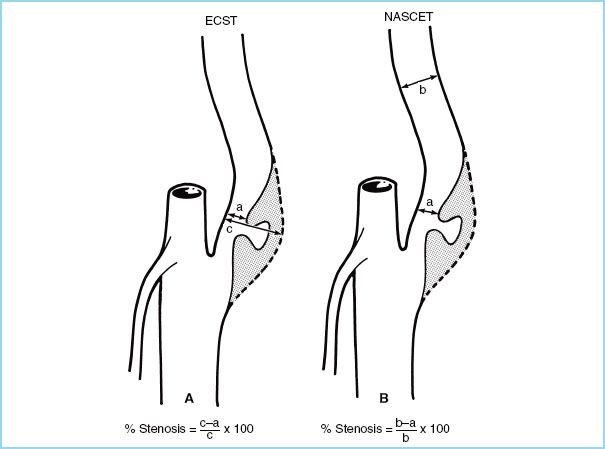

FIGURE 7.4 Commonly used methods for calculating carotid stenosis. A: European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) method. B: North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) method. (Reused from Osborne AG. Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:373.)

1

C. Natural course of carotid artery disease. The severity of carotid artery disease parallels the degree of atherosclerosis in other regions of the body. A cerebrovascular accident or stroke is mainly accounted for by a thromboembolic phenomenon as compared to a hemorrhagic one. Usually a stroke is preceded by one or two TIAs in 60% of cases and the highest mortality occurs in the first 2 years following a TIA [12]. Clinically the risk of stroke from carotid stenosis is evaluated by the absence or presence of symptoms and the degree of stenosis on imaging (e.g., duplex USG).

III. Carotid endarterectomy and carotid angioplasty and stenting

A. Indications for CEA & CAS. The aim of a CEA is to prevent the adverse sequelae of carotid artery stenosis, e.g., a stroke, which can be devastating for the patient and can even lead to death.

1. NASCET and ECST Studies (Fig. 7.4)

a. Both the NASCET and the ECST clinical trials have helped define current guidelines, most notably the 2011 practice guidelines by the ACCF/AHA [7].

b. Several clinical trials have shown a definite surgical advantage over medical therapy alone especially for symptomatic high grade stenosis [5–7].

c. The NASCET revealed that one major stroke would be prevented at 2 years for every six patients surgically treated (number needed to treat [NNT] = 6) for symptomatic patients with a 70% to 99% stenosis and the risk of an ipsilateral stroke would be decreased from 26% to 9%.

d. The European ACST found that a CEA may be of benefit to asymptomatic patients with a high-grade stenosis group (60% or more).

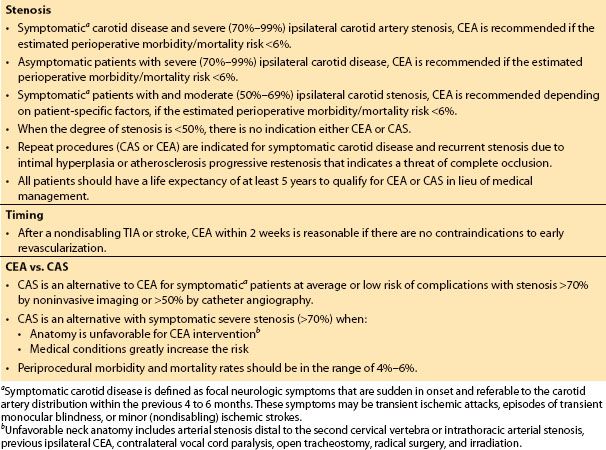

2. ACCF/AHA class I recommendations

a. Table 7.1 outlines recommended management guidelines for carotid stenosis. The class I recommendations for carotid revascularization are briefly enumerated below (the author of this chapter strongly advices reviewing the 2011 practice guidelines by the ACCF/AHA) [7].

Table 7.1 Summary of recommended treatment guidelines for the management of carotid stenosis

b. Class I indications. Patients at average or low surgical risk who experience a nondisabling ischemic stroke or transient cerebral ischemic symptoms, including hemispheric events or amaurosis fugax, within 6 months (symptomatic patients) should undergo CEA if the diameter of the lumen of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery is reduced more than 70% as documented by noninvasive imaging (Level of Evidence: A) or more than 50% as documented by catheter angiography (Level of Evidence: B), and the anticipated rate of perioperative stroke or mortality is less than 6%.

Carotid angioplasty and stenting is indicated as an alternative to CEA for symptomatic patients at average or low risk of complications associated with endovascular intervention when the diameter of the lumen of the internal carotid artery is reduced by more than 70% as documented by noninvasive imaging or more than 50% as documented by catheter angiography and the anticipated rate of periprocedural stroke or mortality is less than 6% (Level of Evidence: B).

Selection of asymptomatic patients for carotid revascularization should be guided by an assessment of comorbid conditions, life expectancy, and other individual factors, and should include a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure with an understanding of patient preferences (Level of Evidence: C).

B. CEA versus CAS

1. Carotid angioplasty and stenting technique has gained tremendous momentum in the recent years and is currently the leading alternative to CEA. The Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy (SAPPHIRE) trial and the recent Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST) have helped shape the latest 2011 ACCF/AHA practice guidelines for extracranial carotid stenosis management [7].

2. In the SAPPHIRE study, Yadav concluded that CAS was noninferior to CEA in regards to total adverse events and lowered event rates for myocardial infarction (MI) and major strokes in high-risk surgical candidates.

3. The most recent clinical trials indicate that CAS may be as safe and effective as the traditional CEA but it must be reiterated that this may hold true for only a small subset of patients, and a generalization must be reserved pending the conduct of further RCTs.

C. Timing of interventions [5–8,13]

1. Mild stroke or TIA. Analysis of the NASCET and the ECST trials found that CEA within 2 weeks of a nondisabling stroke or TIA significantly improved the outcomes compared to medical management.

2. Moderate to severe stroke. The benefit of CEA for patients with moderate to severe ischemic stroke has not been evaluated in RCTs. The high perioperative risk in these patients may preclude consideration for an early CEA. Stable neurologic deficits after a moderate to severe stroke probably vary according to clinical and radiologic features.

3. Emergent. Emergent CEA for an evolving stroke or crescendo TIA has a high operative risk. A 2009 systematic review of 47 nonrandomized studies of CEA for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis reported a rate of perioperative stroke or death of 14% versus 4% for emergent versus nonemergent CEA [13].

CLINICAL PEARL

In symptomatic patients with symptoms with moderate to severe carotid stenosis (50% to 99%), an “urgent” CEA should be performed within 2 weeks.

D. Contraindication to CEA and CAS

1. General contraindications

a. Complete internal carotid artery occlusion

b. Previous stroke on ipsilateral side with significant sequelae

c. Significant comorbidities too risky for either CEA or CAS

2. The major contraindications for CEA are the following:

a. Tracheostomy

b. Neck irradiation

c. Prior neck dissection

d. Contralateral vocal cord paralysis (from previous CEA)

e. Atypical lesion surgically inaccessible

f. Unacceptably high medical risk

3. CAS contraindications include the following:

a. Abnormal vessel anatomy (tortuous, ICA < 3 mm)

b. Diffuse carotid disease

c. Unacceptably high medical risk—recent stroke, severe renal insufficiency

IV. Preoperative evaluation

2

A. Carotid imaging

1. Patients may or may not be symptomatic from a carotid stenosis and this may have no correlation to the presence of a carotid bruit. A positive bruit will however warrant a further investigation by performing a carotid duplex scan. A carotid duplex scan which is a combination of a B-mode USG imaging and a pulse Doppler spectral analyzer for blood flow velocity, is the most common noninvasive investigation.

2. If the carotid duplex scan results prove inadequate, either a computerized tomography (CT) angiogram, magnetic resonance (MR) angiogram, or a carotid angiogram (gold standard) is sought [12].

B. Clinical evaluation. Once it is determined that a carotid lesion is of credible threat to a patient’s well-being and is amenable to intervention based on Doppler USG, CT, MRI, or carotid angiogram, the preoperative assessment of the patient’s comorbid conditions as well as a discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure is swiftly and efficiently conducted.

1. Airway and respiratory system. Cessation of smoking advice to primarily optimize oxygen-carrying capacity. In addition, other advantages include improved postsurgical site wound healing, decreased airway irritability, and secretions if smoking is stopped 1 to 2 months prior to the date of surgery.

2. Nervous system. A careful preoperative neurologic examination must be performed since there is a high incidence of a perioperative stroke. Head position must be checked during the preoperative visit to analyze the cervical range of motion a patient can tolerate when awake, and avoid inadvertent neurovascular and musculoskeletal injuries during general anesthesia.

3. Cardiovascular system. A careful review of cardiac symptoms and exercise tolerance is warranted to determine if invasive and/or noninvasive cardiac testing is needed.

a. Bilateral carotid artery disease significantly increases the perioperative risk of adverse outcomes such that a combined CEA is contraindicated and most surgeons will stage the procedure with a delay of at least 2 weeks in between procedures. The unique dilemma of concomitant significant coronary artery disease (CAD) and carotid stenosis is discussed later in this chapter.

b. The incidence of perioperative MI is reportedly 0% to 4% during a CEA and therefore a high degree of vigilance of its occurrence is adopted. Baseline and serial electrocardiograms along with troponins may be drawn perioperatively at specific times based on institution protocols [14].

c. Establish the blood pressure range for a given patient during the preoperative evaluation and if possible review their medical records and previous hospital visits to determine this value to help guide blood pressure control perioperatively.

d. One should also assess the patient’s need for appropriate antianxiety management on the day of surgery. A thorough bedside preoperative evaluation should complement any pharmacologic agent for anxiety, which should be used judiciously.

C. Perioperative antiplatelet therapy. The risk of developing a TIA in an asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis patient is approximately 1% to 2% per year for the first few years. A European clinical study demonstrated that a reduction in the incidence of TIA can be achieved with the combined administration of aspirin (ASA) and dipyridamole more so than giving either drug alone [15]. Therefore it has become imperative that during the perioperative period, all patients presenting for CEA be maintained on a regimen of ASA and/or clopidogrel.

CLINICAL PEARL

All patients presenting for CEA should be maintained on a regimen of ASA and/or clopidogrel in order to decrease the risk of TIA and stroke.

V. Intraoperative management

A. CEA intraoperative management. As emphasized throughout this chapter, the main goal of intraoperative management involves employing strategies that protect both the brain and the heart and utilizes techniques that lead to a smooth and expedited awakening of the patient for neurologic examination at the end of the procedure.

CLINICAL PEARL

The key to successful management of a CEA is by protecting the heart and brain by preventing ischemic events. This involves maintaining hemodynamic stability with the aid of short-acting vasoactive drugs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree