Primary care physicians whose practices involve mostly older adults need to know the basics of adolescent preventive care because many adolescents will present to their offices for care. Most experts on adolescence recommend annual visits to a physician between the ages of 11 and 21 years, with a complete physical examination at least once each in early adolescence (ages 11 to 14 years), middle adolescence (ages 15 to 17 years), and late adolescence (ages 18 to 21 years).

The emphasis during the annual visit is on prevention and health promotion. The majority of adolescent deaths are due to preventable causes, predominantly accidents, homicides, and suicides. Motor vehicle accidents are the leading cause of death of adolescents and young adults. The major causes of adolescent morbidity include pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), substance abuse, smoking, physical violence, and depression. Young adults (ages 20 to 24 years) have five times the mortality of younger adolescents (ages 10 to 14 years). Because the leading causes of mortality and morbidity are unintended injury or are largely preventable, the focus of care for adolescents is on primary as well as secondary prevention (

Table 238-1). Both biomedical and psychosocial issues should be addressed. Adolescent care emphasizes the cultivation of healthy lifelong habits to prevent heart disease and cancer in particular.

In general, parents are responsible for giving consent for their children’s care until the child reaches the age of 18 years. Adolescents, however, have a greater right than do younger children to participate in their health care decisions. Practitioners should review their state laws regarding the specific services that minors may obtain without the consent of their parents. These services usually are related to pregnancy, birth control, abortion, the evaluation and treatment of STDs (including HIV infection), substance abuse, and sexual assault. Some states also include outpatient mental health services. “Emancipated” minors have the legal right to give consent for their care. These adolescents are married, have children, serve in the military, live apart from their parents, or are homeless. “Mature minors”— adolescents who understand the risks and benefits of treatment and its alternatives—also have the legal right to give consent.

HISTORY TAKING

(1,

2 and

3)Adolescence is a dynamic time in the life cycle and is associated with rapid and dramatic changes in physical, social, and emotional development. The adolescent health history focuses on five contextual and developmental domains:

The unique aspects of the five developmental domains should be explored in each stage of adolescence—early, middle, and late. A convenient acronym for remembering important psychosocial questions in the adolescent interview is HEADS: home environment, education/employment, activities/exercise, drugs, sexuality, and suicide/depression.

Early Adolescence: Ages 11 to 14 Years

Early adolescence heralds the start of dramatic physical changes. Girls undergo rapid spurts of growth, the development of pubic hair and breasts, and changes in the distribution of body fat. Generally, puberty begins in girls 2 to 3 years earlier than in boys. Boys acquire deeper voices, larger testicles, and pubic hair, and acne frequently develops. Early adolescents are preoccupied with looks and anxious about physical changes. In addition, early teenagers move from elementary to middle school, where academic demands are higher, autonomy is greater, and socialization is increased. Their thinking, although increasingly abstract, is for the most part still concrete and oriented to the present. Early teens are focused on self, family, and peers. Sexual exploration and recreational drug experimentation begin. The profound biologic, emotional, and psychological changes experienced by early teens stress the family as they challenge limits and rules and also explore new and sometimes risky behaviors.

Middle Adolescence: Ages 15 to 17 Years

By middle adolescence, the physical development of girls is complete, and most boys are well on their way to the completion of puberty. Although the thinking of middle adolescents remains concrete, many of them are progressing from concrete to abstract, formal, operational thinking. Friends become hugely important. Middle teens also become aware of the larger world and social issues. The growing need for autonomy places teens in conflict with family rules. Middle teens are very aware of academic pressures and are anxious about school and sports performance. They can obtain work permits and driver licenses.

Late Adolescence: Ages 18 to 21 Years

Pubertal development is complete. The late adolescent focuses on vocational and personal development. Older teens are legally responsible for themselves, often living separately from parents and struggling with decisions about further schooling, jobs, or the military. High-risk behaviors peak at this stage, including promiscuity, substance abuse, and eating disorders.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

(1,

2,

3 and

4)Measure and plot on a standard sex-specific growth chart the adolescent’s height and weight. Determine the patient’s body mass index (BMI). Document a blood pressure measurement at every annual visit, although evidence still remains insufficient regarding the value of screening for primary hypertension at this age. Evaluate for scoliosis. Look for evidence of physical abuse. Examine the adolescent’s teeth for cavities, malocclusion, gingivitis, and congenital dental anomalies. Determine the Tanner stage or sexual maturity rating, and keep a copy of one of these two charts in the office for reference. For girls, provide instruction in breast self-examination, and inspect the external genitalia.

Perform a pelvic examination with Papanicolaou smear annually for all girls who are sexually active or 18 years of age or older. Examine boys for gynecomastia and hernias. Check the testicles for abnormal masses or congenital anomalies (boys with a history of undescended testes or a single testicle are at increased risk for testicular cancer). Check the skin for acne.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

(1,

2 and

3,

5,

6,

7,

8 and

9)Perform a random cholesterol determination on teenagers who have a positive family history for early cardiovascular disease or hyperlipidemia. Adolescents who are unsure of their family history should also be screened. Girls with heavy menses, weight loss, or eating disorders or who are extremely athletic should have a screening hematocrit or hemoglobin determination.

Only adolescents at increased risk for exposure to tuberculosis require

tuberculin (

purified protein derivative)

skin testing. These risks include exposure to tuberculosis, homelessness, a history of incarceration, immigrant status, HIV infection or living with an HIV-infected person, and illicit drug use. It is reasonable to test once between the ages of 11 and 16 years if the teenager has no risk factors (see also

Chapter 38).

Sexually active teenagers should be screened for STDs. The frequency of screening is controversial. Usually, girls are screened during each annual pelvic examination, which should include a cervical culture for gonorrhea, immunologic testing of cervical fluid for

Chlamydia infection,

serologic testing for

syphilis, and visual inspection of the genitalia. Adolescent females should be screened for cervical cancer with a

Papanicolaou smear and human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA at age 18 years or at the onset of sexual intercourse. For boys, screening consists of

urine DNA or

leukocyte esterase analysis for

gonorrhea and

Chlamydia infection, serologic testing for syphilis, and visual inspection of the genitalia for HPV (see also

Chapters 107,

117,

124,

125, and

136).

The clinician should offer

HIV testing to all adolescents. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that HIV testing be a routine part of annual medical care, regardless of risk status. High risk includes the use of intravenous drugs, previous infection with an STD, blood transfusion before 1985, exchange of sex for money or drugs, homelessness, a history of more than one sexual partner in the last 6 months, male homosexuality, or a sexual partner with any of the foregoing risk factors for HIV infection (see also

Chapter 7).

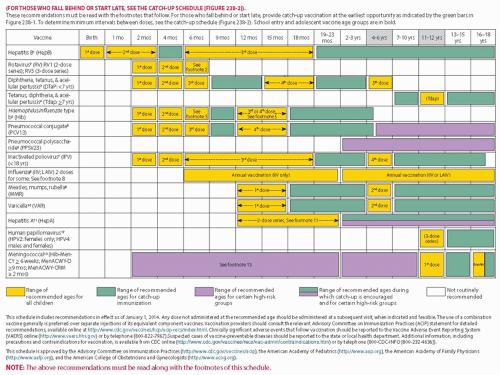

Ensure that the teenager’s immunizations are up to date at every clinical encounter (see

Fig. 238-1).

Tetanus-diphtheria toxoid;

measles, mumps, and

rubella (MMR) vaccine; and

hepatitis B vaccine should be given to the adolescent if the previously recommended doses were missed, not documented, or given before the recommended minimum age (the recommended minimum age for completion of the second dose of MMR vaccination is 4 to 6 years; for varicella vaccination, 12 to 18 months; and for the third dose of hepatitis vaccine, 6 to 18 months). By 11 to 12 years of age, the teenager is due for the tetanus booster if more than 5 years have elapsed since his or her last dose. The adolescent should have three doses of hepatitis B vaccine, two doses of MMR vaccine, and a varicella vaccine if he or she has not had chickenpox. For incompletely immunized or unimmunized adolescents (especially newly arrived immigrants), follow the recommendations of the

Red Book (the most recent edition of the report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics) or the MMWR QuickGuide (published by the CDC) regarding catch-up immunization schedules for adolescents (see

Fig. 238-2 for a catch-up schedule). Adolescents with chronic illness or immunosuppression require

pneumococcal vaccine and annual

influenza vaccine; this includes all adolescents with asthma. College freshmen, especially those who live in group settings and dormitories, require

meningococcal vaccine. Schools routinely request documentation; make certain that the medical records regarding the patient’s immunization status are kept up to date.

HPV infection is the most common STD in the United States (see

Chapter 141). Many HPV strains (particularly 6, 11, 16, and

18) cause cervical cancer, the second most common malignancy in women. Vaccination is recommended for all girls and boys starting at age 11 or 12 years with catch-up vaccination of women and men to age 26. The quadrivalent HPV 6/11/16/18 L1 VLP vaccine (Gardasil) is administered in three doses at 0, 2, and 6 months. The safety profile is considered excellent. The vaccine has demonstrated efficacy against HPV infection (see

Chapters 6,

107,

123, and

141). The duration of immunity is unknown. Vaccination does not replace cervical screening, nor does it treat cytologically evident disease or infection.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access