FIG. 57.1 To begin external cardiac compressions, rescuer should place heel of one hand over lower half of patient’s sternum between nipples in center of chest. (Courtesy Department of Nurse Anesthesia, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.)

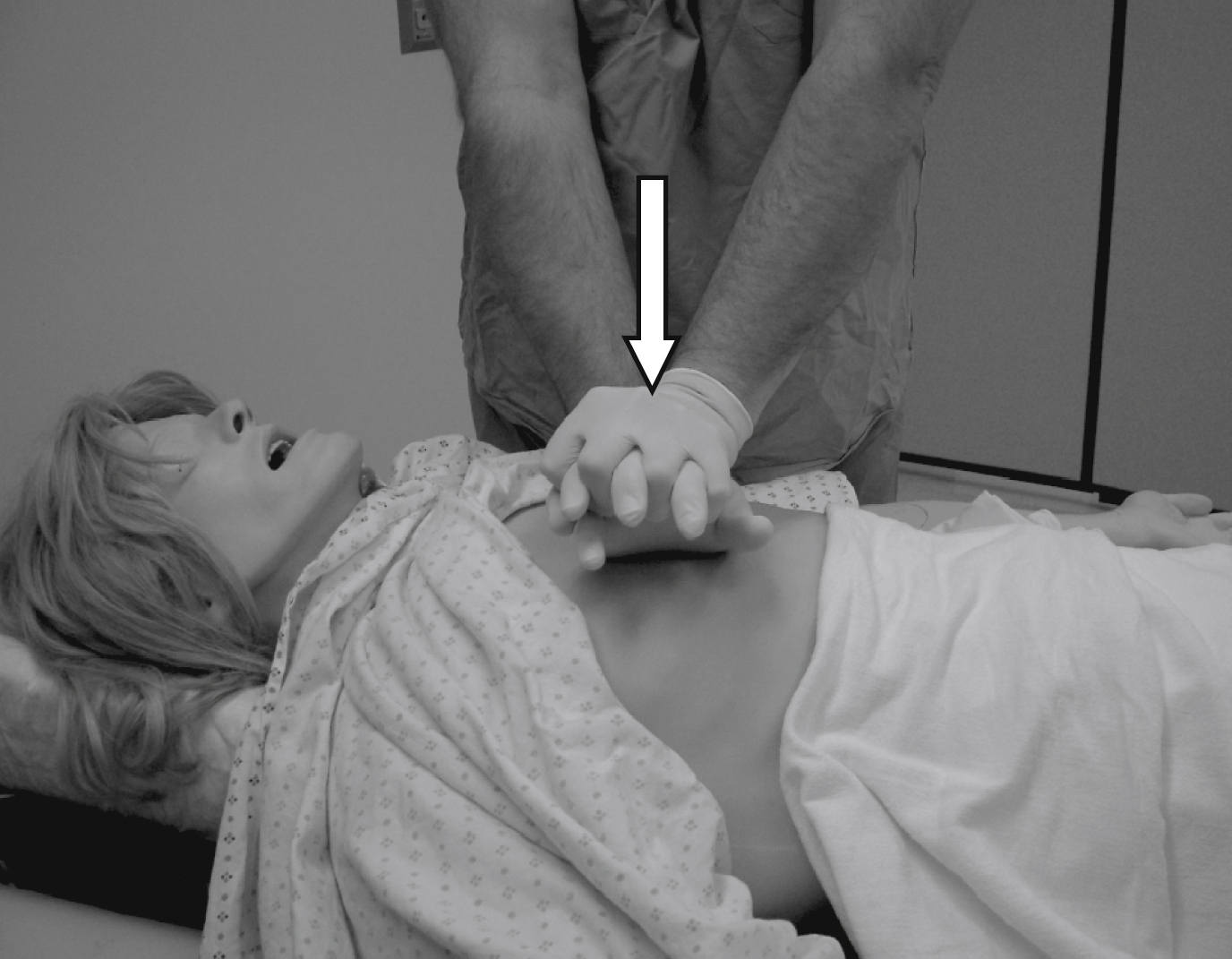

FIG. 57.2 Rescuer’s free hand should be placed on top of hand already positioned on patient’s chest so that hands are overlapped and parallel. Rescuer should keep arms straight and shoulders directly over adult patient’s sternum while pressing down on sternum least 2 inches (5 cm). (Courtesy Department of Nurse Anesthesia, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.)

If two rescuers are present, it is recommended that they rotate giving compressions every 2 minutes. This is done to prevent rescuer fatigue, which can lead to decreased compression effectiveness such as insufficient rate, depth of compression, and incomplete recoil of the chest as mentioned previously. It has been found that significant fatigue and shallow compressions are common after 1 minute of CPR, although the rescuer might not recognize that fatigue affecting effective compressions is present. Rescuers should consider switching roles during any intervention associated with appropriate interruptions in chest compressions such as defibrillation. The rescuers should strive to accomplish this switch in less than 5 seconds.10 The ratio between ventilations and chest compressions is recommended to be 30 compressions to 2 ventilations (30:2).

In children, the sternum is compressed with the heel of only one hand. In infants, the sternum is compressed with the tips of two fingers for one rescuer or the thumbs of the encircling hands of the rescuer when two rescuers are present (Figs. 57.3 and 57.4).13 The compression depth for children should be one third the anteroposterior (A-P) diameter of the chest or approximately 2 inches (5 cm). When treating an infant, the compression depth should be one third the A-P diameter or approximately 1.5 inches (4 cm). As in adults, a rate of at least 100 to 120 compressions/min is also recommended for children and infants.10

The nurse ventilating the patient’s lungs should periodically check the patient’s pulse during compressions as a guide for their effectiveness. If external cardiac compression is done correctly, systolic blood pressure will reach 60 to 80 mm Hg with a diastolic pressure of zero. Mean blood pressure in the carotid artery will seldom exceed 40 mm Hg. Cardiac output from chest compression is approximately one fourth to one third of normal. As a result, compressions must be regular, smooth, and uninterrupted.10

Airway

After chest compressions have been started, rescue breaths by mouth-to-mouth or bag-mask should be delivered. During the initial evaluation of the patient’s responsiveness, the rescuer has already observed the patient’s respiratory status and determined that the patient is not breathing. To facilitate ventilations, certain airway maneuvers should be performed. The PACU nurse should use the head tilt–chin lift maneuver to open the patient’s airway if no evidence of cervical spine trauma exists. The head tilt maneuver is accomplished by tilting the patient’s head backward and hyperextending the neck (see Fig. 29.1). The chin lift involves placing two fingers under the bony portion of the lower jaw near the chin and pushing the patient’s chin upward with moderate pressure (see Fig. 29.2). The head tilt–chin lift maneuver is a combination of both these maneuvers (see Fig. 29.3). For patients with actual or possible cervical spine injury, the airway should be opened using only a jaw thrust without the head extension maneuver. To perform the jaw thrust, the rescuer is positioned at the head of the patient. The rescuer places one hand on each side of the patient’s head and grasps the angles of the patient’s lower jaw and lifts with both hands (see Fig. 29.4). If the jaw thrust does not open the airway in a patient with possible cervical spine injury, the head tilt–chin lift maneuver should be used because adequate ventilation is a priority in CPR.10

FIG. 57.3 In infants, sternum is compressed with tips of two fingers when only one rescuer is present, which frees rescuer’s other hand to open the airway for ventilations. (Courtesy Department of Nurse Anesthesia, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.)

FIG. 57.4 If two rescuers are present, one rescuer can perform compressions with thumbs of encircling hands while other rescuer performs ventilations. (Courtesy Department of Nurse Anesthesia, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.)

Early in the CPR process, a decision should be made concerning the need for an advanced airway. Because the insertion of an advanced airway may necessitate the interruption of chest compressions for many seconds, the rescuer must weigh the need for compressions against the need for an advanced airway device. Deference of insertion of an advanced airway until the patient fails to respond to initial CPR and defibrillation or shows return of spontaneous circulation is acceptable.10

Recommended advanced airway devices include supraglottic devices such as the esophageal-tracheal Combitube, Laryngeal Tube or King LT, laryngeal mask airway, or an endotracheal tube. Unlike endotracheal intubation, subglottic airways do not require visualization of the glottis. As a result, training and maintenance of skills with these devices are usually easier compared with endotracheal intubation. In addition, because direct visualization of the glottis is not necessary, a subglottic airway can be inserted without interruption of chest compressions.10

When the patient’s airway is secured, proper placement of the advanced airway device should be confirmed. This confirmation is especially critical when endotracheal intubation is performed because of the high risk of tube misplacement, displacement, and obstruction. Confirmation of proper endotracheal tube placement should be assessed with auscultation of the lungs to determine whether breath sounds are present and bilaterally equal in both lungs. Auscultation over the epigastric region is an additional method to confirm misplacement of the endotracheal tube in the esophagus. In addition to auscultation, a confirmation device such as an exhaled CO2 detector or an esophageal detector device can also be used. If a capnogram is available, the presence of end-tidal carbon dioxide should be confirmed along with oxygen saturation with an oxygen saturation monitor. A continuous wave from capnography in addition to clinical assessments is considered the most reliable method of confirming and monitoring correct endotracheal tube placement. When proper placement has been confirmed, the advanced airway should be secured in place to prevent displacement and dislodgment. This can be accomplished with tape or with a specially designed endotracheal tube holder in the case of an endotracheal tube.10

All of these advanced airways should be used only by a properly trained rescuer who is experienced with these devices. In many institutions, endotracheal intubations performed in the PACU are often the responsibility of an anesthesia provider.

Breathing

Coronary perfusion pressure gradually rises with consecutive compressions; therefore, a ratio of 30 compressions to 2 ventilations is recommended for adults without advanced airways whether one or two rescuers are present. When the patient is a child or infant, one rescuer should use a 30:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio. If two rescuers are present, a 15:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio should be used.14

When an advanced airway device is in place, a continuous and uninterrupted compression rate of 100 to 120 compressions/min should be maintained. Ventilations of 1 breath every 6 seconds or 10 breaths/min should be simultaneously delivered without interruption of the compression rate. Each breath should take 1 second to deliver with a resulting visible chest rise. Studies suggest that a tidal volume of 8 to 10 mL/kg will maintain normal oxygenation and eliminations of carbon dioxide (CO2). During CPR, oxygen uptake from the lungs and CO2 delivery to the lungs are reduced because cardiac output is approximately 25% to 33% of normal. Therefore, a lower-than-normal minute ventilation can maintain effective oxygenation and ventilation of the patient’s lungs. With the adult patient, a CPR tidal volume of approximately 500 to 600 mL should be adequate.10 Excessive ventilation should be avoided because it has been implicated with gastric inflation resulting in regurgitation and aspiration. Excessive ventilation can also cause increased intrathoracic pressure, decreased venous return to the heart, and decreased cardiac output and survival. The patient should be assessed rapidly for spontaneous breathing and circulation approximately every 5 cycles (2 minutes) of CPR. During this assessment, chest compressions should be interrupted for no longer than 10 seconds.10

The vast majority of patients in the PACU will have intravenous (IV) infusions and will be connected to various monitors including the ECG, pulse oximeter, and other monitors for blood pressure and temperature. If for some reason the patient’s IV catheter has been discontinued or not all monitoring devices are in use (as may be the case when preparing a patient for discharge or transfer from the PACU), intravenous access should be secured and the patient should be reconnected to an ECG monitor as soon as possible. Remember, interruptions to chest compressions must be kept to a minimum. Cardiac rhythm analysis should be performed and arrhythmias should be treated with appropriate pharmacologic interventions. Vital signs such as blood pressure, pulse rate, and temperature should also be monitored and assessed.9

Defibrillation

Based upon evidence provided for the 2015 AHA Guidelines, it is reasonable to expect that a trained health care provider would tailor the sequence of events to the cause of the arrest. In the event of a witnessed arrhythmogenic arrest, a PACU nurse should call for help, retrieve a nearby defibrillator, return to the victim and administer a shock, and immediately initiate CPR.

In the PACU, the code cart with a defibrillator should always be easily available. When two or more rescuers are present (as is most likely the case in the PACU11) and unresponsiveness is determined, one rescuer should begin chest compressions while the other activates the emergency response system and retrieves a defibrillator, administering a shock to a shockable rhythm as soon as possible.9

Defibrillation is the most important determinant for survival in adult VF and VT. If the patient is not already being monitored (e.g., immediately on admission to the PACU from the OR), the patient should be connected to an ECG monitor or defibrillator with monitoring capabilities. Rhythm assessment is imperative for the detection of VF or VT. The PACU nurse must remember that for each minute of persistent VF, the patient’s chance of survival decreases. Survival rates are highest when immediate CPR is provided and defibrillation is performed within 3 to 5 minutes from the onset of the arrest. After VF or VT has been identified, the defibrillation sequence should start immediately.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree