Cancer pain

Introduction

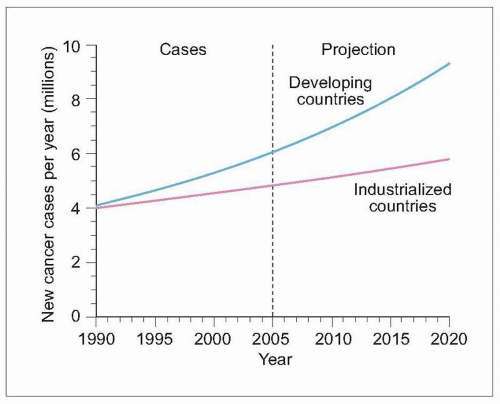

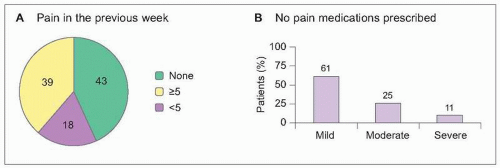

Cancer prevalence is increasing in both industrialized and developing countries, with a marked increase among developing countries (8.1)1. Pain occurs in the majority of patients with cancer, especially among patients with metastatic disease (8.2)2. A recent meta-analysis of 52 studies of adult cancer pain reported pooled prevalence of pain of 53% in cancer patients overall, including 64% among those with advanced, terminal, or metastatic disease, 59% of those undergoing cancer treatment, and 33% after curative treatment3. Pain was rated as moderate to severe by 31% of all cancer patients and 45% with advanced, terminal, or metastatic disease.

8.1 Worldwide cancer incidence prediction. Cancer incidence was recently estimated for industrialized and developing countries. Although the incidence was similar between country categories in 1990, the incidence in developing countries currently surpasses that in industrialized nations, with a prediction for almost 2 of every 3 new cancer patients in 2020 to be residing in a developing country. (Based on Salminen E, et al., 20051.) |

Similar to nonmalignant chronic pain, pain in cancer patients has also been linked to disablity and psychological distress. A survey of 219 hospitalized cancer patients in Taiwan identified pain during the preceding week in 38%4. Patients with pain were more likely to have metastatic disease compared with nonpain cancer patients (82% vs. 41%). Cancer patients with pain also reported a poorer functional status and higher prevalence of anxiety and depression. A multivariate analysis controlling for metastatic disease and functional status showed that pain was an independent predictor of depression.

8.2 Prevalence and under-treatment of cancer-related pain. A representative sample of 601 cancer patients was collected in 20 treatment settings in France, including 5 cancer treatment centres, 4 university hospitals, 5 state hospitals, 5 private clinics, and one home care setting. Patients were not recruited from speciality pain or palliative care practices. A: Pain during the preceding week was reported by 57% of cancer patients, with the majority of these reporting at least moderate severity pain (≥5 on a 0 [no pain] to 10 [unbearable pain] severity scale). Metastatic disease was present in 65% of patients reporting pain. B: One in three cancer patients reporting pain was receiving no pain medication prescriptions. Using the World Health Organization ladder to determine appropriate treatment, 51% of patients were considered to be under-treated for their pain complaints. (Based on Larue F, et al., 19952.) |

Assessment

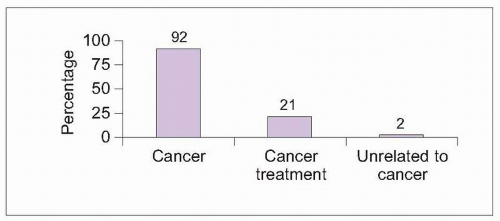

Cancer pain may be caused by cancer directly, cancer treatment, or noncancer conditions (Table 8.1). Cancer patients are also at higher risk for developing painful herpes zoster and PHN. In most cases, cancer-related pain is a direct result of cancer, although about one in four patients experience pain related to cancer treatment (8.3)5.

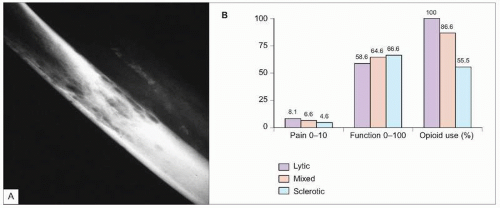

Cancer pain may be caused by musculoskeletal, neurological, and visceral abnormalities. Musculoskeletal pain syndromes may be caused by direct effects on bones and muscles or severe joint deconditioning due to pain or neurological loss of surrounding structures. Bony metastases are more likely to be related to pain and functional disability when lesions are lytic (8.4)7. Neuropathic pain may be caused by direct invasion, surgery or postsurgical scarring, or by radiation or chemotherapy.

Identifying factors contributing to pain is important to allow appropriate understanding of pain complaints and subsequent development of treatment recommendations. For example, common pain syndromes in breast cancer include pain related to bony metastases, postmastectomy pain, and brachial plexopathy related to tumor or radiation (Case 1). While the pain in Case 1 was primarily neuropathic, Case 2 illustrates cancer pain related to a combination of both somatic and neuropathic pain conditions.

Table 8.1 Common causes of pain in cancer patients | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

8.3 Causes of pain in cancer patients worldwide. Cance-rpain specialists in 21 countries in 5 continents (North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia) collected data on 1,095 consecutive patients >16 years old with cancer and chronic pain severe enough to require opioid analgesics. Primary cancer pain sites varied across most body regions among patients, and 70% of patients were diagnosed with metastatic disease. Most patients experienced pain as a direct result of their cancer, with one in five patients reporting a pain condition related to cancer treatment. A minority of patients reported pain complaints unrelated to cancer or its treatment. Average pain severity was rated as moderate (4.7 on a scale from 0 [no pain] to 10 [unbearable pain]). Sixty-five percent of patients also reported additional breakthrough pain, although reporting was significantly higher in English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) compared with Asia, Europe, and South America6. The authors speculated that terminology differences may have resulted in under-reporting of breakthrough pain by non-English-speaking country participants. (Based on Caraceni A, Portenoy RK, 19995.) |

8.4 Lytic bone metastases. A: Radiograph showing characteristic lytic bone metastases. B: Comparison of pain and disability by type of bony metastasis. Adult patients with solid tumors and bone metastases (N=80) were evaluated in a prospective study. Pain severity was rated from 0 (no pain) to 10 (unbearable pain). Functional status was assessed with the Karnofsky performance status index, scoring function from 0 (dead) to 100 (normal). Analgesic consumption was also recorded. Patients with lytic bone metastases had significantly greater pain, disability, and opioid use than patients with sclerotic or mixed metastases (P<0.05). Pain and opioid use were also significantly higher in patients with mixed metastases compared with sclerotic lesions (P<0.05). Mean daily morphine-equivalent opioid dosage was 221 mg in patients with lytic metastases versus 192 mg with mixed lesions and 171 mg with sclerotic lesions. (Based on Vassiliou V, et al., 20077.) |

Case presentations

Case 1

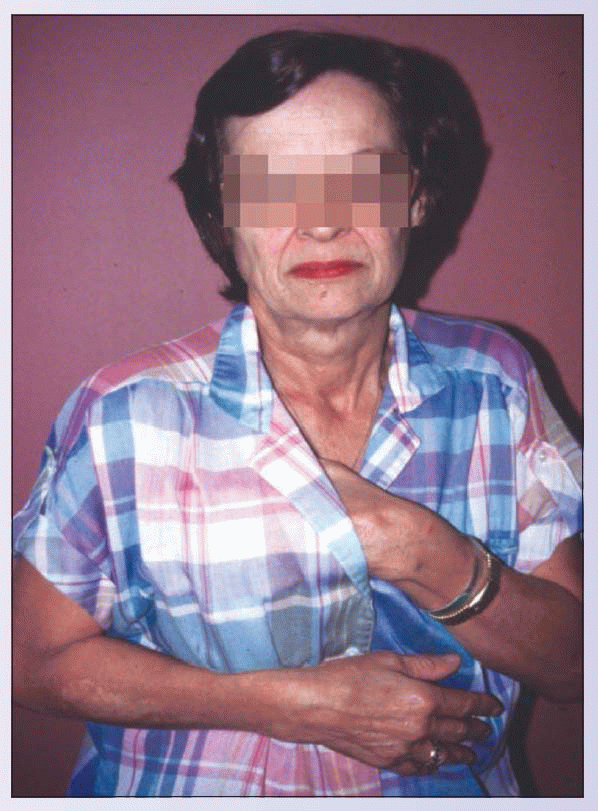

This 67-year-old woman reported hyperalgesia and allodynia over her chest and in her armpit 1 month after a right mastectomy. The pain was a severe, knife-life and burning pain that would abate only with avoiding any movement of her right upper extremity. Consequently, she held her right upper extremity in a splinted position and avoided using it. This resulted in marked disability, frustration, and despair. She was eventually diagnosed with postmastectomy pain, which occurs in up to one in five women following mastectomy. Although postmastectomy syndrome may occur even after lumpectomy, it is most common following mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection. In some cases, there may be associated nerve damage. Postmastectomy syndrome is distinguished from brachial plexopathy, which typically has prominent arm swelling, evidence of cervical root dysfunction, arm burning, and possibly a Horner’s syndrome. This patient was treated with multidisciplinary treatment, including neuropathic pain medications, psychological pain management strategies, physical therapy to avoid developing a frozen shoulder, and occupational therapy to assist in resuming more normal function.

|

Case 2

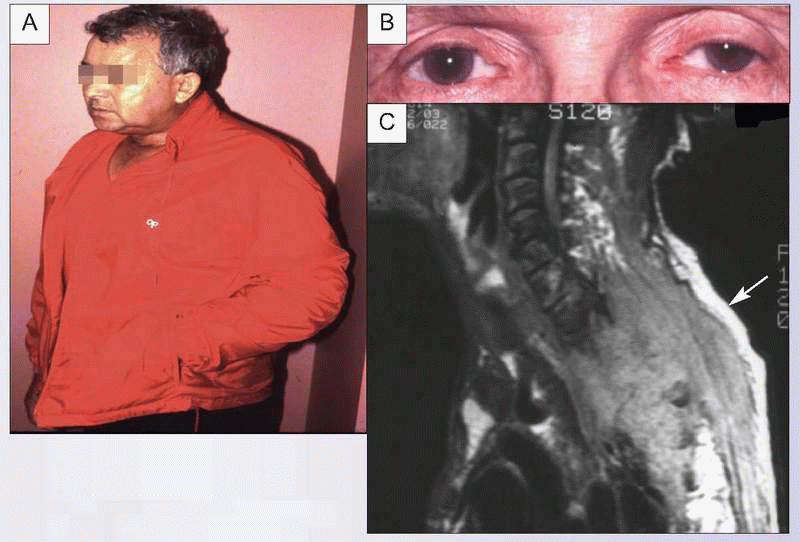

This 78-year-old man was diagnosed with an apical lung tumor. He refused surgical resection and chemotherapy and was treated with radiation. One month later, he was referred for severe chest wall and left upper extremity pain that prevented any activities using the left arm. Although he was seen on a particularly hot summer day, he wore a jacket because his hand and arm felt cold and using the jacket pocket resulted in arm splinting and prevented accidental touching of the hyperalgesic hand (A). Examination revealed decreased sensation to touch over the medial aspect of the left hand (C8-T1 distribution), with hyperalgesia to pin prick over this same distribution. He also had a left Horner’s syndrome, with ptosis and miosis (B). Imaging studies revealed an enlarging Pancoast tumor invading bone, the ipsilateral brachial plexus, and the spinal epidural space (C, arrow). Treatment included steroids, radiation, neuropathic medication, opioids, psychological pain management, and both physical and occupational therapies to improve functional status.

|

Treatment of cancer-related pain

The same principles that guide chronic nonmalignant pain therapy are also used for cancer pain, including use of therapies matched to pain severity and multidisciplinary treatment to address pain, functional impairment, and psychosocial factors. Modifications to medication dosing, route of administration, and implementation of interventional therapies may be needed, especially in patients with refractory cancer pain (8.5)8. Unfortunately, both doctors treating cancer patients and hospice nurses tend to underestimate pain severity among cancer patients, which can result in inadequate treatment2,9.

Medication

Opioids are often necessary in patients with cancer-related pain (8.6)10. Typical starting doses are provided in Table 8.2. As in nonmalignant pain, cancer pain patients rarely achieve complete pain relief with opioid therapy. A survey of inpatients and outpatients with cancer pain in South Africa noted that 94% were treated with prescription medications, with two in three patients considered to be adequately medicated11. Only 21% of patients, however, achieved complete pain relief.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree