Introduction

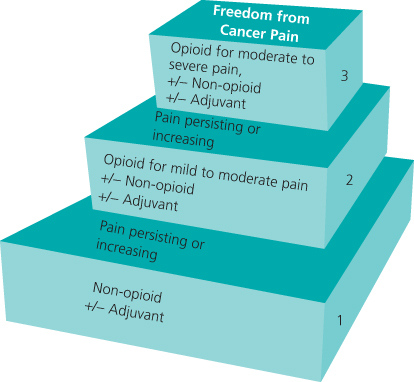

Cancer pain assessment clearly has to encompass both an accurate assessment of the pain and take into account the underlying disease, as well as past, current and proposed treatment. The WHO analgesic ladder (Figure 10.1) when applied appropriately can achieve good pain control in the majority of patients. There are, however, major differences in how it is used and in the resultant outcomes. The principles of the analgesic ladder are as follows:

Generally the evidence for opioids and adjuvant analgesics points to co-prescribing, usually resulting in a reduction in the opioid dose required (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 Areas where adjuvant analgesics may be useful

| Type of pain | Agents with evidence for use |

| Neuropathic Pain | Antidepressants: Despiramine, amitriptyline, duloxetine |

| Anticonvulsants: Gabapentin, Pregabalin | |

| Bone pain | Bisphosphonates, radiopharmaceuticals |

| Bowel obstruction | Anticholinergic drugs, somatostatin analogue |

| Multiple use | Dexamethasone |

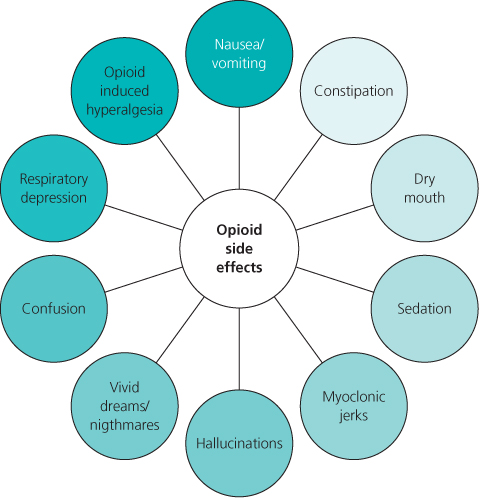

The mainstay for pharmacological management of cancer pain is opioid based. The pure mu agonists are recommended. The constant continuing challenge with opioids for all clinicians managing patients with cancer pain is to find the optimum balance between the desired effect of pain relief and the undesired common side effects. This aim will encompass finding the appropriate opioid and route for the individual patient and appropriate provision for so-called ‘breakthrough’ medication. Anticipatory management of all the common opioid side effects is critical, along with regular assessment to detect early signs of emerging side effects, heralding opioid toxicity (Figure 10.2). Opioid-induced toxicity can have a significant impact on quality of life and arguably, if undetected, quantity of life. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia has been evaluated in both the laboratory and in early situations in the clinic. Following early debate as to the existence of this phenomenon, it is generally agreed that this does exist as a specific phenomenon and can be part of the spectrum of opioid toxicity described already or occur by itself. It certainly should be considered in any patient, particularly on a background of rapid escalation of opioid dose where there is widespread sensitivity in the skin.

The optimum balance with opioids in cancer pain management is achieved with the use of other appropriate drugs and the category of drugs known as the adjuvant analgesics plays a key role in cancer pain management.

Cancer Pain Versus Non-malignant Pain

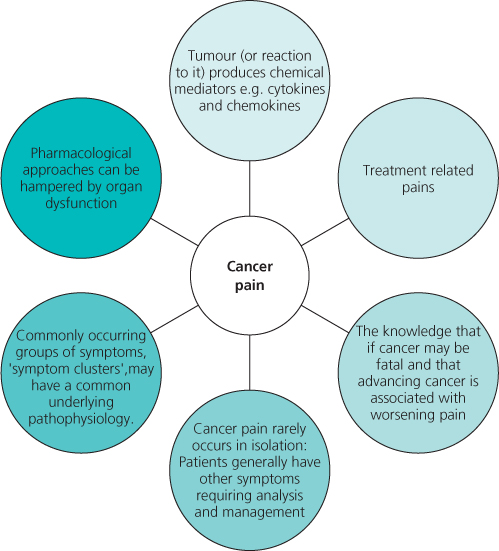

Pain due to cancer can be considered as the spectrum of pains covered in this book but with the addition of five key important factors, as outlined in Figure 10.3. Treatment-related pain can be particularly challenging. Patients may not complain of even very severe pains related to treatment, because of the context in which they are experiencing the pain. Treatment-related challenging pains include chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, hormone and chemotherapy-related arthropathy, radio- and chemotherapy-related mucositosis, radiation burns and idiosynchratic peripheral nerve pains with newer treatments, including monoclonal antibodies

Assessment

The principles of pain assessment clearly apply to cancer pain; however, knowledge of the following is important: