Burns

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

As with all seriously injured patients, one must first insure that a functional airway is present, that air exchange is occurring within the chest, and that intravascular volume is adequate. An additional priority in patients with ongoing thermal injury is to stop the process of burning; this includes removing any metallic objects (which retain heat) and any clothing, particularly synthetics, which may continue to smolder for prolonged periods after the fire has otherwise been extinguished.

In the field, oxygen (100%) by mask should be given, burned areas should be covered with clean sheets, and the airway must be carefully reassessed; depending somewhat on transport time, prophylactic intubation should be considered in patients likely to have had a significant respiratory injury (severe respiratory symptoms, progressive bronchospasm or hoarseness, confinement in a closed, burning space, facial, perioral, or intraoral burns, etc.). Isotonic solution should then be infused and transport initiated.

Estimation of Extent and Depth of Injury

The entire skin surface should be examined for evidence of thermal and other injury and estimation as to the extent and depth of injury made.

“Rule of nines”: The “rule of nines” provides a reasonable initial approximation of the percent of total body surface area (BSA) involved.

In adults, the head (including the neck) and each upper extremity are assigned 9% of total BSA, with the back-buttocks, chest-anterior abdomen, and each lower extremity assigned 18%; the genitalia are assigned 1%.

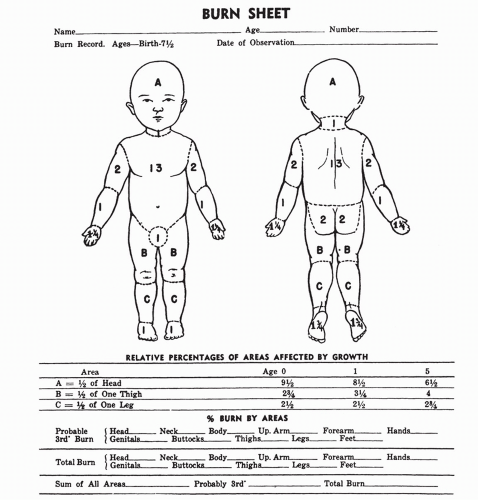

In the newborn, the head is relatively larger and together with the neck represents 19% of the total BSA, with the lower extremities each assigned a percentage of 12.5. For each year of life up to age 10, 1% is subtracted from the head and neck and added to the lower extremities; at age 10, adult proportions are reached. Lund and Browder charts, which are age-specific, provide a more accurate measure of the area of burn in children.

An additional, simple method to estimate percent of involvement is to assign a value of 1% to the patient’s palm and then use this as a way of estimating total percent. Importantly, first-degree burns are not included in the extent of burn injury, unless they account for more than 25% to 30% of the BSA (Table 55-1 and Fig. 55-1).

Classically, the depth of burn injury has been described as first-, second-, or third-degree. More recently, the terms superficial, partial-thickness, and deep, partial-thickness have been used to more fully describe “second-degree” burns; third-degree burns are described as full-thickness burns. This terminology is common and well understood and is thus appropriate and interchangeable.

First-degree burns involve only the epidermis, are characterized by simple erythema that blanches with pressure, are painful, and are not associated with evidence of skin

disruption or blister formation. First-degree burns typically heal within 3 to 7 days, do not scar, and require only symptomatic treatment.

Table 55-1 American Burn Association Grading System

Minor Burns (Outpatient)

Moderate Burns (Inpatient)

Major Burns (Burn Center)

First-degree <15% TBSA

Second-degree 15%-25%

Second-degree >25%

Second-degree <15% TBSA

Third-degree <10%

Third-degree >10%

Third-degree <2% TBSA

Burns of hands, face, eyes, ears, feet, or perineum; inhalation burns; electrical burns; those associated with major trauma and in poor-risk patients (previous medical illness, head injury, cerebrovascular accident, psychiatric illness, closed space injury)

TBSA, total body surface area.

From Harwood-Nuss A, Wolfson A, Linden C. The clinical practice of emergency medicine.

Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996, with permission.

Superficial, partial-thickness burns result in destruction of the epidermis and extend into the outer portion or papillary layer of the dermis; extension into the inner dermal layer (the reticular layer) does not occur. As a result of this, hair follicles and sweat and sebaceous glands are spared. Any visible dermis is red and moist and appears viable; blisters are typically present, and adequate capillary refill is noted. These burns are very painful, and resolve over a 2- to 3-week period, typically without scarring.

Deep, partial-thickness burns involve the inner portion of the dermis (the reticular dermis), do not blanch with pressure, are not painful, and are usually characterized by the presence of blisters. Any underlying or visible dermal tissue typically has a white appearance. Capillary refill is absent, and these injuries are sometimes difficult to differentiate from full-thickness burns. In fact, deep, partial-thickness and full-thickness burns commonly alternate in any given area. These burns require 1 to 2 months to heal and produce significant scarring.

Fourth-degree burns extend into the underlying subcutaneous tissue and may progress further into muscle and bone. These burns may resemble deep, partial-thickness burns and typically require surgical intervention.

Airway Involvement

Thermal injury involving the upper airway may produce few if any signs at presentation; however, rapid airway obstruction may occur as swelling progresses. Both the history and the physical examination are useful in determining those patients at risk for upper airway or pulmonary injury. The following suggest the possibility of airway injury and the risk for the development of airway complications:

Patients who were burned within an enclosed space

The very young or elderly

Patients with abnormalities of mental status, or reported loss of consciousness in the fire

Physical evidence of facial burns

Loss of facial hair including the eyebrows and nasal hair

Pharyngeal burns, hoarseness, or change in voice

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree