Breathlessness

Breathlessness has non-physical as well as physical aspects and, like pain, can be defined by what a patient says it is. It is the unpleasant sensation of being unable to breathe easily. It is common in the terminal stages of cancer: in one survey 70% of 1700 patients experienced breathlessness during their last six weeks of life. It is a particularly distressing and frightening symptom, not only for patients but also for carers. Activity, levels of anxiety, speed of onset, and previous experience may influence patients’ perception of breathlessness and its severity.

While there is often an obvious cause (such as pleural effusion or extrinsic bronchial compression), in some patients no cause is found despite thorough assessment. Little is known about the effects of cachexia on respiratory muscle function; hyperventilation may account for breathlessness in some cases.

Management

Management of a breathless patient should be individualised, but some general principles apply. Many members of an interdisciplinary team can contribute. As well as nursing and medical input, physiotherapy is often helpful, particularly for advice on techniques for conserving breathing, positioning, control of panic, and relaxation methods. Occupational therapists can give essential advice on strategies and practical aids for daily activities. There is good evidence to support breathlessness clinics led by nurses.

In selected patients specific treatment, such as anticancer therapy, can improve control of symptoms and quality of life. The appropriateness of various strategies varies with time, but, for many patients, the disadvantages of travelling to a distant or regional centre may be justified when weighed against symptomatic relief gained from radiotherapy, laser therapy, or stenting of an endobronchial tumour. Pleurodesis should be considered early rather than after repeated pleural aspirations as nearly all patients experience recurrence one month after simple aspiration.

Oxygen

Oxygen is usually seen as a non-specific treatment for breathlessness. Patients can become highly dependent on oxygen therapy; many see it as their lifeline. In patients with chronic lung and heart disease, however, there is good evidence that oxygen therapy is beneficial only in specific situations such as hypoxia or pulmonary hypertension.

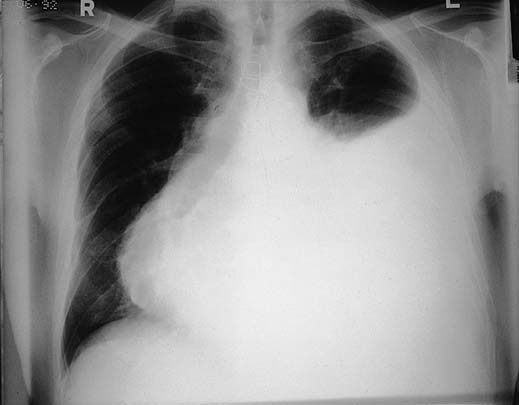

Radiograph of patient with malignant pericardial effusion and secondary pleural effusion causing breathlessness

- Reassurance to patient, family, and non-professional and professional carers

- Explanation

- Advice on techniques to conserve breathing, positioning

- Stream of air such as fan or open window

- Distraction and relaxation techniques

- Consider blood transfusion if patient is anaemic

- Encourage adaptations in lifestyle and expectations

- Pleural aspiration with or without pleurodesis

- Pleuroperitoneal shunt

- Aspiration, with or without percutaneous fenestration

- High dose corticosteroids

- High dose corticosteroids

- Laser therapy

- Cryotherapy

- Stenting

It is not clear whether oxygen is better than air at relieving breathlessness in patients with advanced cancer; further research is needed to identify which patients are most likely to benefit. Meanwhile, the pros and cons of oxygen therapy should be considered on an individual basis. Not all breathless patients are hypoxaemic and, in any case, not all hypoxaemic patients benefit from oxygen therapy. It seems sensible to prescribe a therapeutic trial of oxygen to patients with resting oxygen saturation concentrations <90%. At the least, some form of objective assessment of the benefits, or not, of oxygen in an individual patient should be performed; and oximetry may be helpful. If relatively long term use is likely, an oxygen concentrator rather than cylinders should be considered for patients at home. The use of nasal speculae can avoid some of the inconvenience of a mask. The gas can be humidified, but this is noisy.

Few patients require continuous oxygen. For others, explanation and individualised coping strategies, including a bedside or hand held fan, sometimes combined with non-specific drug measures, such as opioids or anxiolytics, are more appropriate and often more successful.

Coping with anxiety and panic

The vicious cycle in which anxiety aggravates breathlessness and breathlessness, in turn, creates further anxiety is experienced to some degree by most breathless patients, regardless of the cause. Some may experience a severe panic attack and become convinced that they are about to die. Such attacks are more common than is acknowledged. Patients should be advised of measures that they can initiate to allow them to regain control. These have been summarised as “Stop, purse lips, drop (shoulders), and flop.” It is important to teach lay and professional carers how to cope; simple strategies such as gently massaging the breathless person’s back can be helpful.

Research on the use of benzodiazepines in breathless patients with chronic non-malignant lung disease is equivocal and, in patients with cancer, does not support their use in unselected patients. If anxiety seems to be a major component or trigger of breathlessness and cannot be relieved by non-pharmacological measures, then a therapeutic trial of a low dose benzodiazepine either regularly or as required seems sensible. Concern about possible respiratory depression is usually unfounded, and any such concern should be weighed against the potential benefit of treatment.

Opioids

The relation between opioids and respiration is not simple; if used inappropriately, opioids can induce respiratory depression, which is determined by pathophysiology, previous exposure to opioids, rate and route of dose titration, and coexisting pathology. However, low dose oral opioids can improve breathlessness, sometimes dramatically, though the precise mechanism of action is unknown.

The dose of opioid can be titrated in the same way as when it is used for pain control, but lower doses and smaller increments should be used. In patients not previously exposed to opioids, as little as 2.5 mg of normal release morphine every four hours may be sufficient. If a patient is already receiving controlled release morphine, many convert to a normal release preparation and allow for a dose increment. For patients unable to swallow, subcutaneous diamorphine can be used. Concurrent laxatives should be prescribed.

Nebulised drugs

If a trial of a nebulised drug is thought appropriate, then nebulised normal saline should be used in the first instance.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| • Reverse hypoxia | • Claustrophobia |

| • Sense of wellbeing | • Discomfort |

| • Patients, families, and professionals feel they are doing something | • Drying effect |

| • Difficulties in communication | |

| • Distancing | |

| • Risk of patient/relatives smoking | |

| • Cost |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree