BLUNT INTESTINAL INJURY

CASE SCENARIO

A 47-year-old woman is the restrained driver in a high-speed motor vehicle crash. She has a prolonged extrication time and is brought to the trauma center boarded and collared. She is hemodynamically stable, but she complains of right lower extremity pain. On examination, she has an obvious deformity of the right femur and bruising on her left shoulder and anterior abdomen superior to the umbilicus. Her abdomen is soft, with mild periumbilical tenderness.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Blunt bowel or mesenteric injury (BBMI) occurs in approximately 1% of blunt traumas and is the third most common intra-abdominal injury, surpassed only by trauma to the liver and spleen. The most common site of gastrointestinal injury involves the proximal jejunum, followed by distal ileum, mid small bowel, colon, duodenum, and stomach, in decreasing order.1 The incidence of blunt small bowel injury rose steeply with the introduction of high-speed travel after WWII, and again spiked with the first seatbelt laws in the 1970s.2,3 Motor vehicle crashes account for 70% to 85% of all BBMIs, followed by other rapid deceleration mechanisms including pedestrians struck by cars, bicycle crashes, assaults, falls, blasts, and horse kicks. In pediatric cases, child abuse should also be considered.

Blunt bowel injury causing perforation carries a high mortality, which correlates directly with time to repair. Perforation repaired within 8 hours carries a mortality of 4%. A delay of as little as 8 to 12 hours, however, has a mortality of 9%, and at 24 hours it rises to 15%. Morbidity also increases, with the risk of abscess and surgical site infection quadrupled after 24 hours.4,5

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Deceleration injuries inflict damage via a combination of three types of forces. A crushing injury causes direct tissue damage, including lacerations, perforations, and hematomas. This often occurs when the bowel is compressed between two fixed objects, such as the spine posteriorly and any other anterior object (steering wheel, seatbelt, or bike handlebar). Shearing forces between fixed retroperitoneal structures and free-floating bowel can also tear the bowel wall or its supplying mesentery. This most commonly occurs at the proximal jejunum near the fixed ligament of Treitz, the terminal ileum near the retroperitoneal cecum, or the transverse and sigmoid colons at their retroperitoneal attachments.6 Lastly, bursting injuries occur when intraluminal pressure exceeds the bursting strength of the small bowel wall, generally thought to be 120 to 140 mm Hg. This intraluminal pressure can easily be accomplished by relatively small external forces when the bowel lies in a closed-loop position.7

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Clinical findings of BBMI include abdominal tenderness, rigidity, and absent bowel sounds. Unfortunately, these symptoms are vague, and therefore insensitive and nonspecific to bowel injury. In fact, studies have shown that abdominal tenderness and rigidity are present in less than 50% of BBMI cases.8 Furthermore, relying on physical examination alone requires mandatory hospital admission, repeated examinations by the same observer for best results, and a neurologically intact patient with minimal distracting injuries. Even in the awake evaluable patient, clinical examination will miss up to 20% of clinically significant injuries.9 Abdominal bruising, on the other hand, has higher sensitivity. The seatbelt syndrome (seatbelt use, bruising, and vertebral fractures) is well described, and is associated with BBMI in up to 21% of cases.10,11 Chance fractures and abdominal wall tears are also commonly associated. Despite this, the physical examination remains quite unreliable, and the use of it as the sole indication for surgery has led to negative laparotomies in up to 40% of cases, which carries an unwarranted morbidity of 5% to 20%.12,13

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

See Table 29–1.

WORKUP AND CHOICE OF IMAGING

BBMI is relatively rare and difficult to diagnose, especially in this era of increasingly conservative management. It is important for the surgeon to be aware of the relative strengths and shortcomings of the available diagnostic modalities.

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory tests are unreliable in the diagnosis of BBMI. The white blood cell count is often elevated in trauma patients at presentation, regardless of the presence or absence of bowel perforation. A leukocytosis that does not correct with time can suggest injury; however, reliance upon this method can lead to a delay in diagnosis. Amylase has been reported to be significantly higher in BBMI than non-BBMI, but no reliable cutoff has been established.11

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

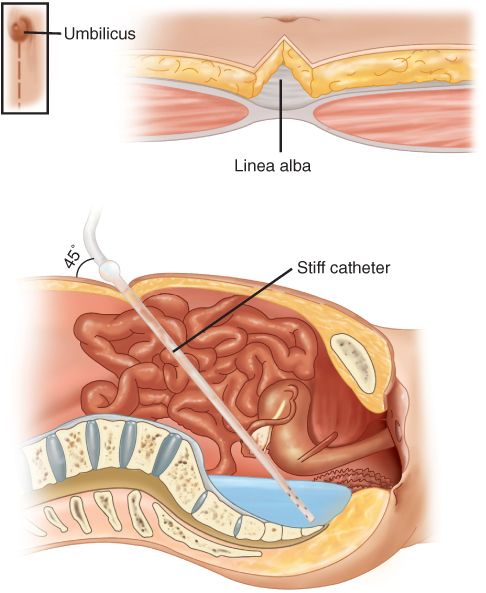

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) or aspirate has also been used as an adjunct to BBMI diagnosis. It has a sensitivity of >90% for both hemoperitoneum and bowel perforation. Its sensitivity increases with the time from injury, and so it plays a lesser role at initial presentation. Today, DPL can help define the etiology of free fluid detected by another modality. The traditional definition of a positive DPL is fluid recovered from the lavage with a red blood cell (RBC) count >100,000/mm3; a white blood cell (WBC) count >500/mm3, amylase >100 IU/L, or the presence of bile, bacteria, or particulate matter. These criteria confer a sensitivity of nearly 100%; however, the positive predictive value is only 35%. Several attempts to refine the positive DPL criteria have been made, and results show that a ratio of WBCs to RBCs of greater than 1:150 has a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 99% when performed greater than 3 hours from time of injury.14 Several other iterations have been proposed, including alkaline phosphatase levels and ratios comparing aspirate counts to venous blood. DPL does have several drawbacks, including the risk of bowel perforation or vascular injury, and the introduction of air and fluid into the abdomen may obfuscate subsequent imaging (Table 29–2 and Figures 29–1 and 29–2).

Abbreviations: RBCs, red blood cells; WBCs, white blood cells.

Figure 29–1 Illustration of an infra-umbilical approach to diagnostic peritoneal lavage. This is an open approach by which the peritoneum is identified and grasped. The catheter is directed into the most dependent area within the pelvis where fluid might be expected to pool. It is then connected to a bag of saline, which is then infused via gravity drainage. (Reproduced with permission from Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Biliar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Matthews JB, Pollock RE. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery, 9th Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010.)

Figure 29–2 Positive diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPA), showing at least 10 cc of intra-abdominal frank blood. (Reproduced with permission from Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Biliar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Matthews JB, Pollock RE. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery, 9th Ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010.)

Ultrasound

Ultrasound

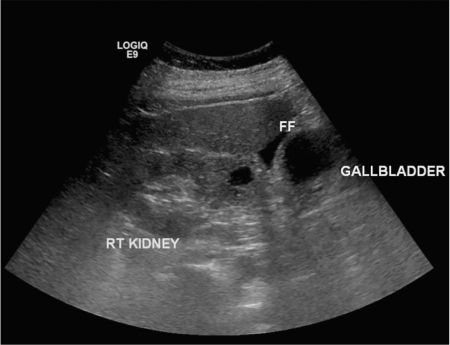

Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) was first coined in 1971 and is now a readily available and reliable bedside diagnostic tool for trauma surgeons. Surgeon-performed FAST examinations have been validated against radiologists in multiple observational studies.15 It is most useful—when combined with chest and pelvic radiographs—in identifying the most common sources of hemodynamic instability: cardiac tamponade, hemothorax, tension pneumothorax, hemoperitoneum, or pelvic fractures with retroperitoneal bleed. Each of these immediately life-threatening injuries can be diagnosed within minutes of presentation without leaving the trauma bay. FAST has a sensitivity of 80% to 86% and specificity of 95% to 99.7% for detection of at least 50 cc of free fluid.16,17 Because of its low sensitivity, it has less of a role in the stable patient able to undergo further testing, and its role in the workup of BBMI is minimal. The character of the free fluid cannot be reliably identified, and so FAST cannot differentiate blood from enteric fluid. Its positive predictive value for BBMI is 38%.11 A negative FAST scan in no way rules out injury. For further discussion of the FAST examination, please refer to Chapter 3: Bedside Ultrasound for Surgeons, and Chapter 26: Intra-Abdominal Hemorrhage (Figure 29–3; see Figure 3–1).

Figure 29–3 Positive focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination showing free fluid in the right upper quadrant or Morison’s pouch. FF, free fluid.

Computed Tomography

Computed Tomography

Since its inception in the late 1960s, computed tomography (CT) has evolved as the key diagnostic modality in trauma patients and is often an extension of the secondary survey. Because of its sensitivity and specificity, it is essential for the evaluation of patients with blunt abdominal trauma.

Investigation of BBMI should include intravenous contrast unless the patient has an allergy or other contraindication, such as severely impaired renal function. Intravenous contrast provides detailed imaging of mesenteric vasculature, as well as information about the condition of the bowel wall.

Oral contrast was initially thought to be crucial for the evaluation of bowel perforation in trauma patients. Subsequent studies, however, showed its administration led to diagnostic delays. In addition, oral contrast puts the patient at significant risk for aspiration of the contrast agent, a potentially devastating complication. Multiple studies have shown that oral contrast has a sensitivity of just 8% to 15% for bowel perforation, and that the vast majority of cases have other CT findings indicative of injury.18,19 Extravasation does, however, have a specificity nearing 100%.18 Sensitivity increases with gastric and duodenal injuries and, if there is high suspicion for these injuries, its use is recommended. Likewise, if colonic injury is suspected, rectal contrast can be administered. Often, contrast is utilized in follow-up imaging after a suspected injury is identified at initial evaluation. Some caution must be taken in interpretation of contrast extravasation as false positives can occur, e.g., vascular or urinary disruption with extravasation of IV contrast can look similar to oral contrast. Unfortunately, CT findings of bowel wall discontinuity and contrast extravasation are rare. Secondary findings of BBMI are far more common, and will be reviewed in detail in the following section.

IMAGING FINDINGS

CT Scan

CT Scan

Peritoneal fluid is by far the most common finding in blunt abdominal trauma, and is quite sensitive for both solid and hollow viscous organ injury.17,20 In a 2012 study, Hassan et al. explored 45 patients with blunt abdominal trauma, and 93% of patients with significant bowel or mesenteric injury had free fluid on their preoperative CT.21 Free fluid can be of high or low attenuation depending on the presence of active bleeding. Location of free fluid can also be important, with interloop fluid, seen as a “triangle sign” on CT, being more specific for bowel injury.22 The amount of free fluid is also indicative of injury; however, as bowel injuries are accompanied by solid organ injuries in approximately 50% of cases, the specificity of free fluid is diminished. Isolated free fluid, without evidence of solid organ injury, is seen in approximately 3% of blunt traumas.23 The significance of this scenario, although uncommon, is fiercely debated, and its management varies widely. Several authors have proposed mandatory laparotomy for isolated free fluid, quoting a 54% to 78% therapeutic laparotomy rate.20,23 Others have reported therapeutic laparotomy rates as low as 10% and a positive predictive value of only 30%, recommending observation or further workup studies rather than surgery.24,25 Rodriguez et al. in 2002 looked at 10 studies evaluating over 16,000 patients with isolated free fluid on CT. They calculated a 27% therapeutic laparotomy rate when the indication was isolated free fluid, and concluded further workup should be performed in the scenarios.23

Bowel wall thickening is defined as small bowel thickness of greater than 3 mm, or colonic thickness greater than 5 mm. It is the next most common finding, occurring in 45% to 55% of small bowel and 19% of colonic injuries. Its specificity ranges from 76% to 84%.1,21 One study showed colonic thickening to be more specific (97%), and therefore a more concerning finding than small bowel thickening.22 It is important to evaluate the entire length of bowel, since focal thickening can occur with contusion. Diffuse thickening of the bowel could be due to over-resuscitation or global ischemia, and not directly related to injury.1 Alternatively, diffuse thickening can be a late finding of peritonitis following perforation. Poorly distended bowel can have the appearance of thickened bowel wall and is the main source of false-positive findings.

Bowel wall enhancement should also be evaluated. It, too, can be focal or diffuse, and can have increased or decreased enhancement, both of which can be indicative of injury. Increased enhancement indicates an injury with vascular involvement, with increased permeability and leakage. Decreased enhancement suggests ischemia, and if focal, can be specific for vascular involvement and possible compromise.

Pneumoperitoneum, or “free air,” is a finding nearly synonymous with bowel perforation. However, even full-thickness perforations will sometimes release no air, and its sensitivity is only about 20%.1 Specificity is also lower than expected due to bladder ruptures, diaphragm injuries, and barotrauma, all of which can produce pseudopneumoperitoneum. Previous DPL will also give rise to false positives. Specificity for bowel injury is therefore about 97%.26 Retroperitoneal air is more confined, stays in better proximity to its source, and is therefore more specific to colonic or duodenal injury.

In general, mesenteric findings are either highly sensitive or highly specific, but never both. This is largely due to the very forgiving, redundant blood supply to the bowel. However, when mesenteric findings are associated with simultaneous bowel wall thickening or the mesenteric finding is in close proximity to the mesenteric border of the bowel, sensitivity and specificity increases dramatically to 69% to 77% and 44% to 100%, respectively.27,28

Identification of a mesenteric vascular injury obviously raises concern for hemorrhage or resulting bowel ischemia, both of which would necessitate intervention. Active hemorrhage can be identified by IV contrast extravasation. Thrombosis can be seen as “beading” of the vessel or abrupt termination. These findings are best seen on coronal or sagittal views, and are subtle and often missed by novice readers.22 While each of these findings has a relatively poor sensitivity of 26% to 50%, their specificity and positive predictive value are greater than 90%.

Mesenteric infiltration, or fat stranding, is the result of mesenteric edema and is a common finding with a sensitivity of 69%. As with many of the other mesenteric findings, it has poor specificity, and when seen as an isolated finding, provides little information.

Mesenteric hematomas are seen in 45% of bowel injuries; however, when explored they are seldom found to be clinically significant or require intervention. The use of delayed imaging may capture ongoing bleeding within hematoma, which would manifest as a higher attenuation.29 Hematomas are commonly seen as wedge-shaped intra-mesenteric fluid collections.

Multiple studies have examined combinations of CT findings in search of the best predictive model for small bowel injury. Malhatra et al. showed that the positive predictive value of each individual CT finding was poor and insufficient to warrant laparotomy. In CTs with only one suspicious finding, 64% were found to be false positives. On the other hand, 83% of the scans with more than one abnormal finding were found to have BBMI. These findings were statistically significant.17 The EAST multi-institutional gastrointestinal injury study, a trial compiling over 275,000 blunt abdominal trauma patients from 95 trauma centers, provided a logistic regression model that showed that the presence of free fluid, pneumoperitoneum, and bowel wall thickening in combination were the best predictors of BBMI, with a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 79%. After several different regression model iterations, the only clinically relevant model suggestive of small bowel injury included abdominal tenderness, peritoneal signs, and free fluid without solid organ injury on CT, which yielded a sensitivity of 56% and specificity of 94%11 (Table 29–3 and Figures 29–4 through 29–10).