Key Clinical Questions

What are the initial priorities for the patient with severe or life-threatening bleeding?

Is the bleeding medically remediable, or does it require structural intervention (interventional radiology or surgery)?

Does the patient have a coagulopathy or a platelet disorder based on history and examination?

What explains an elevated INR; an elevated PTT; a low platelet count?

How should coagulopathy be managed in the bleeding patient?

If a coagulopathy is present, what should be done to prepare a patient for an invasive procedure?

The orthopedic service requests Hospital Medicine consultation for bleeding from a wound site and for rapid drop in hematocrit. The patient is a 73-year-old woman admitted 2 weeks prior to consultation because of acetabular breakdown at the site of a previous left total hip replacement. On the day of admission, she underwent a revision of the left hip with bone grafting and trochanteric fixation. Because of substantial blood loss during the procedure, she required 4 units of packed red blood cells. Her postoperative course was complicated by transient hypoxemia related to volume overload and by delirium that gradually cleared by hospital day 7. Unfortunately, while anticipating transfer to a rehabilitation facility, she experienced dislocation of the left hip. She returned to the operating room on hospital day 13 for complex revision of the left hip arthroplasty. Postoperatively, she had continuous oozing of blood from the left hip incision. On hospital day 15, her hematocrit dropped from 31 to 27 and she was noted to have a melenic stool. Her past medical history is notable for hypertension, and a history of peripheral vascular disease. She had a right carotid endarterectomy 6 years prior to admission and also had an emergent bowel resection about four years prior, due to intestinal ischemia. Other medical issues include degenerative joint disease of both hips and knees, gastroesophageal reflux, depression, fibromyalgia, and a history of a deep vein thrombosis following a right total knee replacement 1 year prior. Her medications at the time of consultation include fluoxetine, lamotrigine, amitriptyline, fentanyl patch, morphine as needed for breakthrough pain, atenolol, furosemide, nifedipine, ranitidine, and cefazolin for “wound prophylaxis.” She had been receiving enoxaparin for thrombosis prophylaxis but this was discontinued the day prior to consultation because of continued bleeding. |

Initial Bedside Priorities

Initially, the goals for the hospitalist should be resuscitation of the unstable patient, control of bleeding, and prevention of further bleeding. Bedside evaluation of patients with apparent brisk bleeding (gastrointestinal, pulmonary, postpartum) includes vital sign measurement and assessment for adequate perfusion (mentation, capillary refill, urine output). Evidence of hemorrhagic shock mandates aggressive resuscitation using large bore intravenous access for intravenous fluids and blood products.

Life-threatening bleeding events may include intracranial hemorrhage (intracerebral, subdural, epidural, subarachnoid), gastrointestinal hemorrhage, massive hemoptysis, postpartum hemorrhage, and retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage portends a 25% to 30% in-hospital mortality. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from varices predicts substantial in-hospital mortality.

Similar to management of severe traumatic hemorrhage, the bedside approach should minimize the time between recognition of severe or life-threatening bleeding and bleeding control. Each diagnostic intervention, including history, physical examination, laboratory testing, and radiographic testing should have the potential to lead directly to therapeutic intervention. The adage of the trauma surgeon that “the only diagnostic test that is absolutely required before operating on the severely injured trauma patient is a type and cross for blood products” emphasizes the absolute focus on intervention that is required for acute, severe bleeding. In general, control of active bleeding requires a multidisciplinary approach that may involve surgery, interventional radiology, and/or endoscopy. Table 76-1 provides guidance regarding the appropriate consultative services to engage urgently for each of the serious or life-threatening hemorrhagic problems along with the anticipated approach.

| Bleeding Event | Urgent Consultation | Expected Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage | Neurosurgery | Assessment for surgical intervention* |

Traumatic brain injury associated hemorrhage

|

| Assessment for surgical intervention* |

Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage

|

|

|

| Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage |

| Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage may require angiography for localization and potential intervention |

| Retroperitoneal hemorrhage |

|

|

| Postpartum hemorrhage | Obstetrics | Assessment for surgical intervention* |

| Massive hemoptysis |

| Bronchial artery embolization has a role in stabilizing patients and may be adequate primary treatment. |

What are the initial priorities for the patient with severe or life-threatening bleeding? Is the bleeding medically remediable or does it require structural intervention (interventional radiology, endoscopy, or surgery)? The patient is actively bleeding from the wound site, but the nursing staff reports that they are changing the dressing once a shift and feel the bleeding is manageable. The patient herself is disappointed at “another setback,” but generally feels comfortable. She has not experienced shortness of breath, chest pain, abdominal pain, or nausea. She is thirsty. She noted that her bowel movement this morning was “very dark and smelly.” The nurse confirms melena and reports that the hemoccult was positive. Examination shows an older woman in no distress. She is alert and oriented. Blood pressure 140/96, pulse 74 and regular. Mucous membranes are dry. Jugular venous pressure is estimated at 5 cm. Lungs are clear. Cardiac exam is normal. The abdomen is soft, with minimal tenderness over the epigastrium. The left hip wound is oozing blood and the thigh is swollen, somewhat indurated, and mildly tender. Available labs include a hematocrit of 29.1%, platelets 401,000/mm2. The INR is 1.9, and the aPTT is prolonged at 43 seconds (normal range, 22.1–34.0 sec). Creatinine is 0.7 and BUN is 25. Analysis: Although the melena is worrisome, the patient appears to be hemodynamically stable. She is mentating well. Her blood pressure is adequate and her pulse is normal. Bleeding from the wound is troublesome but controlled at present. The hematocrit is adequate, but may not reflect acute bleeding. |

|

Initial interventions for this patient should be assurance of adequate intravenous access and alerting gastroenterology to the potential need for endoscopic evaluation. At this point, resuscitation is not an issue and it seems likely that there is time for assessment of medical issues that may be contributing to her bleeding.

Secondary History and Physical Examination for Bleeding Disorders

Systematic assessment of bleeding disorders requires a working knowledge of normal hemostasis. The two major mechanisms that contribute to clotting in distinctive but interrelated fashion are (1) platelet adhesion, activation, and plugging (“primary hemostasis”) and (2) the coagulation cascade that generates a fibrin clot (“secondary hemostasis”) with resultant consolidation of the platelet plug. Endothelial injury that exposes the circulating blood to subendothelial tissue factor and collagen activates both clotting mechanisms. Platelets adhere to exposed collagen and to exposed collagen-bound von Willebrand factor. Collagen exposure also activates the platelet, inducing a change in the shape of the platelet to a more irregular form that enhances adhesion and interaction with other platelets. Activated platelets discharge fibrinogen, fibronectin, von Willebrand factor, platelet factor 4, factor V, and factor VIII, promoting adhesion and aggregation of other platelets. In addition, activated platelets secrete adenosine diphosphate, adenosine triphosphate, and serotonin that also increase platelet activation. Thrombin generated by the coagulation cascade also aggressively activates platelets.

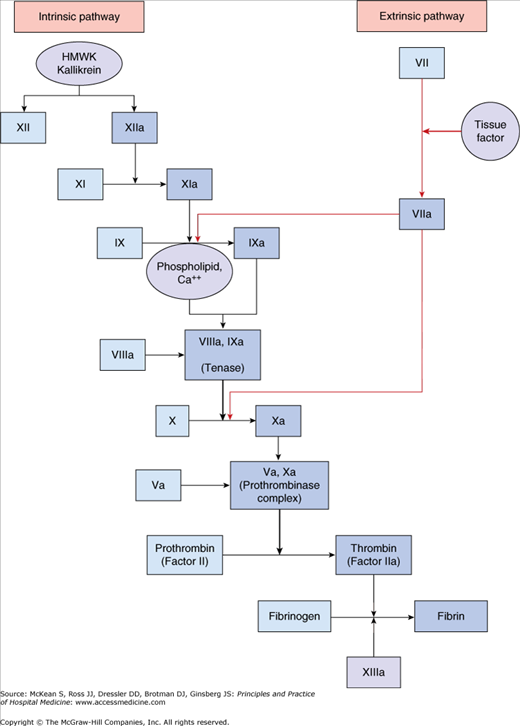

Exposure of blood to tissue factor in the subendothelium initiates the coagulation cascade, as depicted in Figure 76-1. This complex interaction of enzymes and cofactors generates fibrin clot that stabilizes the platelet plug. Deficiencies of components in the clotting cascade lead to bleeding disorders of varying severity depending on the qualitative and quantitative defect. Platelet adherence, activation, and aggregation in combination with the explosive production of a fibrin clot via the coagulation cascade has the potential to induce excessive thrombus formation. Antithrombin, tissue factor pathway inhibitor, and activated protein C limit the extent of clot propagation.

Clotting requires complex interaction of the injured endothelium with platelets and the coagulation cascade. Defects or deficiencies in any of these steps may lead to excessive bleeding or bleeding risk.

The history and physical examination are critical components in the evaluation of a patient with a suspected bleeding disorder. It is important to determine if the patient has had significant bleeding in response to past hemostatic challenges such as dental extractions, surgery, trauma, or childbirth. Ask about each previous surgery in detail, seeking surgical reports of bleeding, need for transfusion, repeated operations, or potential anatomic contributors to operative or perioperative bleeding. Immediate bleeding suggests primary hemostatic defects (ie, platelet abnormalities or vascular endothelial abnormalities, such as blood vessel fragility in senile purpura or scurvy), whereas secondary hemostatic defects (ie, clotting factor abnormalities) typically cause delayed bleeding.

Patients with defects in secondary hemostasis may report a history of hemarthosis or other deep tissue bleeding. A history of mucosal bleeding usually indicates a defect in primary hemostasis. Examples of mucosal bleeding include epistaxis, oral bleeding, gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding (without a local cause such as malignancy), hemoptysis, and protracted menstrual bleeding. Inquiring specifically about transfusion requirements, interventions such as suturing or packing, and the need for hospitalization allows estimation of bleeding severity.

A history of bleeding since infancy or early childhood suggests an inherited disorder. Eliciting a family history of abnormal bleeding can be helpful when considering inherited bleeding disorders and coagulopathies. Lack of such a history, however, is not sufficiently sensitive to exclude a hereditary process. Genetic mutations can arise de novo. Variable penetrance may mask disease in relatives. Recessive genetic defects will not be clinically apparent in relatives with one functional copy of the gene. Further, sometimes congenital coagulopathy may be inapparent until a major hemostatic challenge.

Review of a patient’s medication list should include assessment of prescribed, over-the-counter, and herbal remedies. Warfarin and heparin products cause iatrogenic defects in secondary hemostasis. Platelet dysfunction induced by aspirin, clopidogrel, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can cause bleeding in the setting of normal platelet counts and coagulation parameters. Other medications, such as sulfonamides and vancomycin, may contribute to bleeding through drug-induced thrombocytopenia. Quinine-containing beverages (such as tonic water) or medications can also cause thrombocytopenia. Herbal agents (particularly the “g” herbs such as ginseng, garlic, ginko) have been linked with bleeding.