Key Clinical Questions

What causes jaundice?

How are biliary obstruction and cholangitis diagnosed?

What are the best imaging modalities?

What treatment strategies should be employed in patients with biliary obstruction or cholangitis?

When should procedure or surgical intervention be considered in patients with cholangitis?

Introduction: Jaundice

This chapter describes clinical conditions manifested as a result of acute or subacute biliary disease. Particular focus is on conditions that frequently present to the inpatient setting, including jaundice, which is frequently a symptom of biliary or liver disease, as well as acute obstruction or infection within the biliary tract.

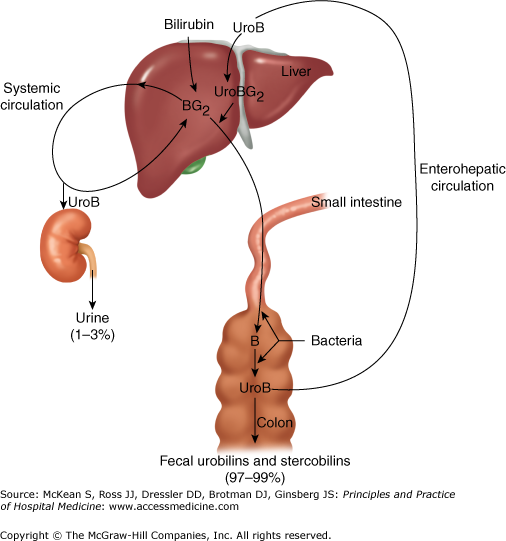

Jaundice is a yellowish discoloration of the skin, the conjunctivae, and other mucous membranes caused by hyperbilirubinemia (56206090). Generally, the serum bilirubin level needs to exceed 2.5 to 3 times the upper limit of normal (0.5–1.0 mg/dL) before jaundice is apparent. Jaundice is typically recognized earliest under the tongue, followed by within the sclera (sclera icterus), prior to it manifesting in the skin. Jaundice usually results from a pathologic process that interferes with the normal metabolism and excretion of bilirubin (56206090). Physiologically, bilirubin is the product of the breakdown of the hemoglobin in senescent red blood cells. Splitting of the four pyrrole ring of heme produces biliverdin, which is then reduced to bilirubin. Water-insoluble bilirubin is transported from the spleen to the liver, where it is rendered more water soluble by conjugation to glucuronic acid. Conjugated bilirubin is excreted into bile and subsequently into the gut, where it is broken down by bacteria into urobilinogen, some of which is converted into stercobilinogen and excreted in the stool, and some of which is transported to the kidneys and excreted in the urine. The stools of patients with obstructive jaundice, who cannot excrete bilirubin into the gut, have pale stools and dark urine, the latter due to greater-than-normal urinary excretion of urobilinogen.

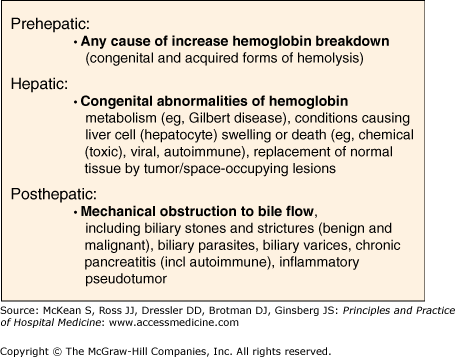

Prehepatic jaundice results from any process that causes an increased rate of hemoglobin breakdown (hemolysis) (56206094). Congenital and acquired conditions cause hemolysis. Congenital conditions that lead to hemolysis include sickle cell syndrome, thalassemia, and spherocytosis; these conditions lead to increased breakdown of red blood cells and hemolysis. Infectious etiologies may lead to massive lysis of red cells, including the malaria parasite (Plasmodium falciparum causes blackwater fever). Iatrogenic causes of hemolysis due to various drugs can occur, and autoimmune hemolytic syndromes can also lead to prehepatic jaundice. More than 900 drugs, toxins, and herbs are known to cause liver injury, and more than 2000 deaths per year are attributed to this cause in the United States. The mechanisms of–and predispositions to–drug-related liver injury are complex. However, many of these reactions result in cholestasis, which is often reversible when the drug is withdrawn. Drugs frequently associated with cholestasis include anabolic steroids, oral contraceptives, chlorpromazine, ciprofloxacin, cimetedine, phenytoin, captopril, erythromycin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and others.

Fractionation of the unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin in the serum of patients with hemolysis and other causes of prehepatic jaundice will typically show a predominance of unconjugated (indirect, or water-insoluble) bilirubin. Laboratory findings in hemolysis include a decreased serum haptoglobin level and an elevated peripheral blood reticulocyte count.

Intrahepatic mechanisms of jaundice include liver cell (hepatocyte) swelling or death (necrosis), and may be caused by viral hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis, drug or chemical toxicities, or autoimmune disease. Congenital abnormalities of bilirubin metabolism, such as unconjugated (indirect) hyperbilirubinemia seen in Gilbert disease, can occasionally cause sufficient elevation of serum bilirubin for an individual to develop clinical jaundice. Replacement of normal liver parenchyma by malignancy (primary or metastatic) can cause jaundice by compressing normal adjacent tissue and compressing bile canaliculi.

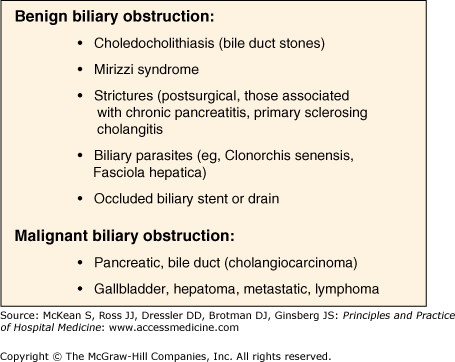

Mechanical obstruction to bile flow will cause jaundice. Common causes are bile duct stones (choledocholithiasis) and cancers involving the head of the pancreas. Rare causes include benign biliary strictures (eg, postsurgical, those associated with chronic pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis), pancreatic pseudocysts, bile duct parasites, biliary varices, and inflammatory pseudotumor.

Introduction: Biliary Obstruction and Acute Cholangitis

Acute cholangitis describes infection of the bile, typically by gram-negative bacteria (eg, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, Serratia, Pseudomonas). The presenting symptoms of pain, jaundice and fever constitute Charcot triad, and are indicative of acute bile infection. When the biliovenous pressure exceeds about 40 mm Hg, bacteria can migrate into the bloodsteam. The addition of hypotension and confusion to Charcot triad suggests sepsis, and the combination of five symptoms makes up the Pentad of Reynolds. Unrelieved, acute cholangitis carries close to 100% mortality. Even when the biliary tree is decompressed, acute cholangitis carries a mortality of around 5%.

In developed countries, the common causes of acute cholangitis include bile duct stones, benign biliary strictures (eg, postsurgical, chronic pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis and obstructed biliary stents and drains (catheters) (56206102). Malignant biliary strictures rarely present with acute cholangitis, but unrelieved, the chronic biliary obstruction of biliary and pancreatic cancers can lead to biliary sepsis and liver abscesses. In tropical climates, biliary parasites (eg, Clonorchis sinesis, Fasciola hepatica) can cause biliary obstruction and cholangitis.