Key Clinical Questions

What views are standard to evaluate the acute abdomen?

Which radiograph view is the most sensitive for detecting a small pneumoperitoneum?

What are the conditions simulating air under the diaphragm?

What are the causes of air-fluid levels on an erect abdominal image?

How do you quantify the amount of gas normally seen in the bowel?

What are the radiologic signs of bowel ischemia?

What are the most common abnormalities associated with acute pancreatitis?

Introduction

Despite the availability of newer imaging modalities to look for intestinal obstruction or perforation, the supine abdominal radiograph (KUB) remains indispensible for evaluating a patient with abdominal pain due to the ease and ready availability for rapidly screening patients with abdominal pain. The standard field of view extends from the lung bases to the pubic symphysis, thereby framing the genitourinary system, imaging kidneys, ureters, and bladder. Additional views include an erect chest radiograph, erect abdominal view, and left lateral decubitus.

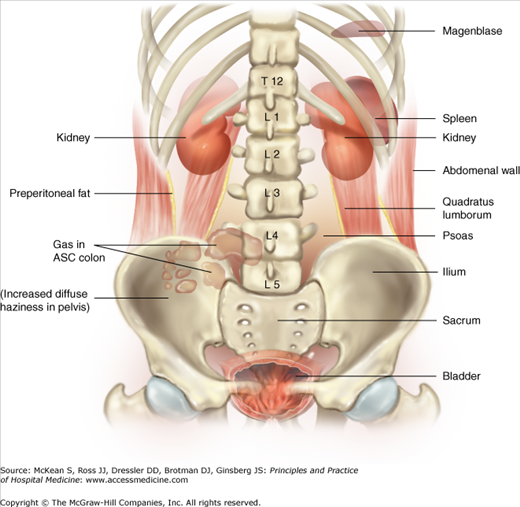

Figure 109-1 is a line diagram pointing out the twelfth ribs, lumbar transverse process, kidneys, psoas line, inferior liver edge, terminal ileum, sacroiliac spine, gas in the ileum and jejunum, gas and feces in the transverse colon, haustral folds, and descending colon. A thin layer of adipose tissue should be visible as a lucent line between the transverse abdominal muscle and the peritoneum extending from above the lateral margin of the liver to below the iliac crest and between the dome of the bladder and the pelvic peritoneum.

Figure 109-1

Anatomic line drawing (including right kidney, psoas line, properitoneal fat line, inferior liver edge, terminal ileum, sacroiliac joint; twelfth rib, left psoas, haustral folds, lumbar transfer process, gas and feces in transverse colon, gas in jejunum, descending colon, gas in ileum).

The abdominal radiograph is not symmetric and in fact there is significant variation in a “normal” KUB as seen in Figure 109-2. Systematic review of examinations may be facilitated by use of a checklist (see Table 109-1).

|

In order to better perceive structures on abdominal radiographs and to better correlate physical exam and imaging findings, it can be helpful to study coronal anatomy images of computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (see Chapter 110, (Table 109-2)).

| Organ | Usually seen | Potentially seen | Not seen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | X | ||

| Spleen | X | ||

| Kidneys | X | ||

| Stomach | X | ||

| Duodenum | X | ||

| Small intestine | X | ||

| Cecum | X | ||

| Colon | X | ||

| Bladder | X | ||

| Prostate | X | ||

| Retroperitoneal fat | X | ||

| Gallbladder | X | ||

| Pancreas | X | ||

| Adrenal glands | X | ||

| Ovaries | X | ||

| Uterus | X | ||

| Ureters | X | ||

| Lymph nodes | X | ||

| Mesentery | X | ||

| Vasculature | X |

Air helps to identify hollow viscous structures on radiographs. The anatomic rendering reveals the colon coursing from the right side of the pelvis, up to the liver, across to the spleen, and then down to the rectum. The presence of adipose tissue may assist interpretation. For example, a thin layer of fat is often seen between the dome of the bladder and the pelvic peritoneum as a lucent line. Location of this layer may be an important clue signifying an enlarged bladder (or urinary retention) as the cause of the patient’s abdominal pain. Tissue-fat interfaces with the adjacent bowel facilitate assessment of organ size.

The erect chest radiograph is used to detect pneumoperitoneum, but it may also provide important clues to other causes from the chest that mimic an acute abdomen, including congestive heart failure from acute myocardial infarction, widened aorta seen in aortic dissection, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumonia, and pleural fluid collections. The erect abdominal radiograph does not provide additional information to the standard KUB and erect chest film.

Radiation Exposure

The KUB delivers a higher dose of ionizing radiation than a posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph because the abdomen is almost always a thicker body part. The greater penetration provides enhanced visualization of lung bases and may identify lower lobe lung processes or pleural effusions associated with abdominal pain. It is particularly important to communicate with the radiologic technologist regarding the priority areas for imaging when the patient is too large for a single 14 × 17 inch image. This can decrease duplication of exposure for completion of examination and repeated examinations that delay patient care.

Communication

|

Screening Plain Films

Plain films readily image ribs; lumbar vertebrae and appendages, especially transverse processes; sacrum; pelvis (iliac crests, acetabula, pubis); femoral head; and neck and may provide important clues to the patient’s overall health. Patients with end-stage renal disease or endocrine disorders have characteristic bony changes and a screening plain film may uncover an underlying malignancy that has a prediction to bony metastasis.

Ribs, spine, and pelvic fractures can suggest location of soft tissue injury. If fractures are identified in the lower ribs and lumbar transverse processes, consider soft tissue injury to the liver, spleen, or kidney. Spine and sacroilliac (SI) joints may indicate chronic arthritic changes.