Bacteremia and Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections

David K. Warren

Bacteremia is a common complication in the critically ill. Bloodstream infections can be secondary to a recognized infection site, or primary infections either without an obvious source, or from the intravascular devices commonly used in critical care. Central venous catheters (CVCs) are the most common source of primary bloodstream infection in critically ill patients, and provide a unique opportunity for pathogens to enter the bloodstream. CVCs become infected through multiple mechanisms. The intra- and extraluminal portions of the catheter or the catheter hub(s) become colonized by bacteria that then enter the bloodstream. Rarely, contaminated intravenous solutions can create outbreaks of bacteremia with uncommon pathogens. Potentially, hematogenous seeding from bacteremia originating at another source can occur. Successful treatment of catheter-associated bloodstream infection is more difficult than simple bacteremia, as organisms on intravascular catheters exist within a slime-like biofilm, reducing their susceptibility to antimicrobial therapy and host defenses.

Local infection of the catheter insertion site presents as inflammation and purulent drainage from the entry site. However, local signs of infection are typically absent in catheter-associated bacteremia. Embolic phenomena distal to the catheter (e.g., septic pulmonary emboli) are also highly suggestive of a catheter-associated infection, although not commonly seen. More often, the clinician is faced with a critically ill patient who is febrile without an obvious source and has a CVC in place.

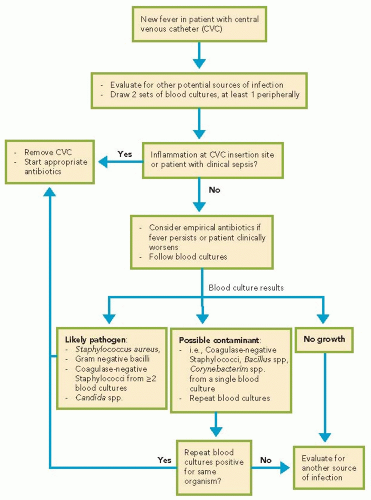

Determining if a CVC is the source of a new fever presents a diagnostic and management challenge. A conservative strategy of removing all catheters and replacing them at new sites at the first sign of fever would benefit some patients, but also leads to the removal of many uninfected CVCs, unnecessarily exposing patients to the risks of line replacement. A reasonable approach would be to draw blood cultures, and then immediately remove the catheter if there are obvious signs of infection at the insertion site (especially in the case of nontunneled catheters) or the patient is in septic shock. If a thorough evaluation does not reveal a source of infection and the patient is stable, it is reasonable to leave the catheter in place, follow the blood cultures, and start empirical antibiotics at the clinician’s discretion. If the cultures become positive, the catheter can be removed and a new catheter placed at a different site, if still indicated.

Because the sensitivity and specificity of blood cultures are imperfect, multiple strategies have been studied in an attempt to improve the diagnosis of

catheter-associated bloodstream infection. Currently, two methods are practical for widespread application. The first takes advantage of the continuous monitoring system for blood cultures used in most modern microbiology laboratories. Blot et al. found that, in cases of catheter-associated bloodstream infection, a blood culture drawn from a catheter became positive for growth faster than a paired sample from a peripheral

venipuncture. If a catheter-drawn blood culture becomes positive for growth at least 2 hours earlier than a peripherally drawn culture obtained at the same time, this strongly suggests the catheter as the source of the bacteremia. The other common method is culturing segments of catheters after their removal. A variety of techniques have been studied, but the semiquantitative roll plate technique described by Maki et al. remains the most common. Documenting significant colonization of a catheter with the same organism isolated from blood cultures provides strong evidence that the catheter is the source of infection. An approach to suspected catheter-associated bloodstream infection in the intensive care unit is presented in Algorithm 38.1.

catheter-associated bloodstream infection. Currently, two methods are practical for widespread application. The first takes advantage of the continuous monitoring system for blood cultures used in most modern microbiology laboratories. Blot et al. found that, in cases of catheter-associated bloodstream infection, a blood culture drawn from a catheter became positive for growth faster than a paired sample from a peripheral

venipuncture. If a catheter-drawn blood culture becomes positive for growth at least 2 hours earlier than a peripherally drawn culture obtained at the same time, this strongly suggests the catheter as the source of the bacteremia. The other common method is culturing segments of catheters after their removal. A variety of techniques have been studied, but the semiquantitative roll plate technique described by Maki et al. remains the most common. Documenting significant colonization of a catheter with the same organism isolated from blood cultures provides strong evidence that the catheter is the source of infection. An approach to suspected catheter-associated bloodstream infection in the intensive care unit is presented in Algorithm 38.1.

TABLE 38.1 Management of Bloodstream Infections by Common Pathogens

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|