CHAPTER 7 Back Schools and Fear Avoidance Training

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

Back schools can be defined as interventions that include group education about low back pain (LBP), appropriate self-management of LBP, training about how to live and how to adapt activities of daily living while coping with LBP, and recommendations for general and back-specific exercises.1 Fear avoidance training, on the other hand, is intended for individual patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) and harmful or inappropriate beliefs or behaviors about their pain. Although the two types of training are reviewed in this chapter as distinct interventions, there is considerable overlap among modern back schools based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) methods and fear avoidance training programs founded on similar concepts. Categorizing these interventions is intended to increase homogeneity among the studies reviewed and to improve the precision of recommendations concerning these interventions.

History and Frequency of Use

The Swedish Back School was introduced by Zachrisson-Forssell in 1969 based on her knowledge about the intervertebral disc, spinal anatomy and physiology, and ergonomics.2–3 Patients attending back schools were initially taught how to protect spinal structures during daily activities; education about back-specific exercises were later added to the program.4 Back schools were eventually incorporated into comprehensive multidisciplinary programs for CLBP.5 The use of education grew after the Scottish spine surgeon Gordon Waddell proposed a new theoretical framework for the treatment of LBP based on his observations that the natural history and epidemiology of LBP suggest that it is benign and self-limiting, and that patients needed to be informed of these facts in order to recover.6

Lethem and colleagues7 introduced the model of fear avoidance in 1983, and a questionnaire for measuring this concept was published by Waddell and colleagues8 a decade later. The central concept of this model is that behavior, for some patients with CLBP, is driven largely by fear of pain. This concept was further outlined by Vlaeyen and Linton9 in 2000, who postulated that confrontation and avoidance are the two extreme responses that patients can exhibit to this fear of pain. Whereas the former leads to gradual reduction of fear over time and eventual recovery, the latter perpetuates and exacerbates this fear, which may generate a phobic state in patients with CLBP. Several studies have shown that physical performance and self-reported disability cannot solely be explained by sensory and biomedical parameters, and that they are also associated with cognitive and behavioral aspects of pain.10–14 Behavior that is believed to be caused by fear of movement is commonly observed among persons with CLBP who have been told or experienced that the “wrong movement” might cause a serious problem and should be avoided, which may increase their risk for prolonged disability.12,15

It is difficult to estimate frequency of use for back schools among those with LBP. However, it has been reported that the number of back schools operating in Sweden in 1984 was approximately 300, with 1000 specialized pain clinics operating in the United States in 1986, more than 40 such clinics in the United Kingdom in 1987, and in excess of 70 specialized clinics in The Netherlands in 1992.16 The use of some form of education in the management and prevention of LBP is now common, and most conservative treatment approaches include some discussion about minimizing biomechanical risk factors and improving lifting techniques.17

The association between biomechanical risk factors and lifting techniques is a persistent myth, and prospective studies have not found that interventions aimed to improve ergonomics have reduced the risk for LBP. Modern back schools educate patients about the knowledge gained from these studies and generally do not educate patients about perceived correct lifting techniques (Figure 7-1). Modern back schools in fact expose patients to performing activities that were previously not recommended, such as jumping and bending their backs while lifting. However, this approach is controversial among professionals and may contribute to the divergent results from trials evaluating the effectiveness of back schools, which represent a heterogeneous intervention that cannot easily be studied.

Procedure

In back schools, education is generally given about the anatomy of the spine, including structures that are commonly thought to be involved in the etiology of LBP. Methods for diagnosing LBP may be discussed, as may be spinal biomechanics and important concepts related to pain in general.18–20 Information is also given about the epidemiology of LBP, its general prognosis over short and extended periods, and the strong possibility of recurrence. Appropriate management options for LBP may be described, including advice on how to live with LBP and adapt activities of daily living if necessary. Education about general and back-specific exercises is also provided; some back schools may include supervised exercise in their curriculum. Back schools are typically given by a physical therapist, or other health care provider with specialized training, to small groups of 8 to 12 participants. They may be delivered in an occupational setting or in a clinical setting as part of a spinal multidisciplinary rehabilitation program and often require multiple sessions given over a few weeks.18–19

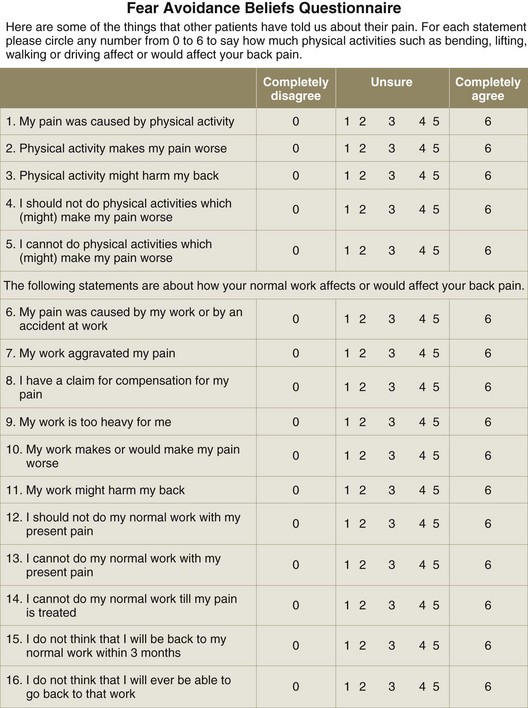

Fear avoidance training is usually given to individuals with CLBP identified as having behavioral risk factors for further chronicity. It is often delivered in secondary care settings by physical therapists with advanced training, behavioral specialists, or nonsurgical spine specialists. Fear avoidance training includes much of the same basic education about LBP, but focuses more on overcoming behavioral barriers to recovery through graded activities of daily living and exercises. This intervention is named after the concept of fear avoidance, or kinesiophobia, which involves avoidance of common activities due to fear that they will exacerbate symptoms. Propensity for fear avoidance in patients with chronic pain can be assessed by validated questionnaires, including the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) or the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ).8,21,22

Theory

Mechanism of Action

Providers should not assume that adequate and correct education about LBP has already been provided by another clinician, regardless of how long symptoms have been present. Patients with CLBP often fail to discuss their fears with health care providers unless asked directly because they do not want to receive unfavorable answers to their questions, dislike further questioning by health care providers about this topic, or worry that their fears will be belittled. This should be considered when providers are explaining the results of any diagnostic tests. Although clinicians appreciate that negative test results that indicate a lack of serious pathology, patients may perceive such tests as having failed to identify the cause of their pain. Clinicians must therefore carefully explain how these results should in fact reassure the patient about the absence of serious pathology (Figure 7-2).

Classic back schools teach about spinal anatomy and ergonomics to encourage protection of the spinal structures, although the impact of this information on patients’ fear has not been addressed. Cherkin and colleagues23 reported that although patient knowledge about the spine was improved following attendance in back schools, the effect on pain and disability was sparse compared with other treatments in patients with acute LBP. Behavior that derives from fear avoidance is inhibitory and may contribute to chronicity and even learned helplessness.25 At present, we do not know whether this inhibition leads to a gradual development of depression, with its low psychomotor level in all dimensions. Although automated movements are unconscious, they may be brought to conscious analysis and observation in patients with CLBP, which can occupy more brain capacity and reduce physical performance.

If CLBP is perceived by patients as a threatening situation, anxiety will give priority to thoughts and information related to their fear. The cognitive activation theory of stress attempts to explain how pain leads to neurophysiologic activation and has proposed that a stress alarm occurs when there is a discrepancy between what is expected and what is experienced by the individual.26 Although the discrepancy is not an immediate threat to their health, a sustained state of related anxiety may lead to CLBP through established pathophysiologic responses. The challenge in patients with CLBP is to balance information and expectancies regarding spinal structures and the adoption of pain behavior. A positive response outcome expectancy (e.g., coping) may reduce the stress response whereas negative response outcome expectancy (e.g., hopelessness) may increase the risk for sustained activation. Interventions such as back school and fear avoidance may improve CLBP by increasing knowledge, which decreases false expectations, lending to fewer instances of discrepancies in their experience.

Indication

These interventions are used mainly for nonspecific mechanical CLBP and have not been evaluated for patients with serious somatic or psychiatric comorbidities that may require concurrent psychological or psychiatric care. The use of CBT and medications for CLBP is discussed elsewhere in this text (i.e., Sections 4 and 8). The ideal CLBP patients for each of these interventions are briefly described here, based on the authors’ clinical experience.

Assessment

Before attending back schools or receiving fear avoidance training, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating these interventions for CLBP. Certain questionnaires (e.g., TSK, FABQ) may help identify subsets of patients with CLBP who may benefit from specific interventions aimed at addressing those issues (e.g., fear avoidance training) (Figure 7-3).

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Back Schools

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found conflicting evidence to support back schools when compared with undefined placebo interventions with respect to improvements in pain, function, and return to work.27 That CPG also found moderate evidence that back schools are more effective than brief education, exercise, or SMT with respect to improvements in pain and function, both in the short term and in the long term. That CPG concluded that back schools should be considered as one possible option for short-term improvement of CLBP.

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found low-quality evidence as to the effectiveness of back schools for CLBP.28

Fear Avoidance Training

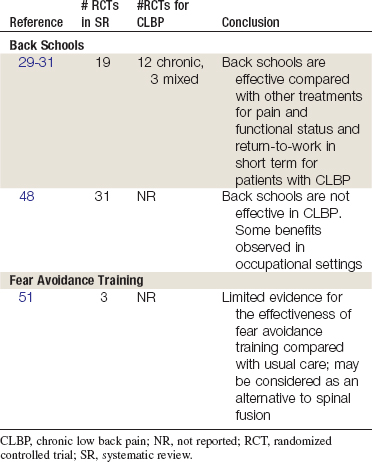

Findings from the aforementioned CPGs are summarized in Table 7-1.

TABLE 7-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations On Back Schools and Fear Avoidance Training for Chronic Low Back Pain*

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Back Schools | ||

| 27 | Europe | Consider as possible option for short-term improvement of CLBP |

| 28 | Belgium | Low-quality evidence of effectiveness |

CLBP, chronic low back pain; CPG, clinical practice guideline.

* No CPGs made specific recommendations about fear avoidance training as an intervention for CLBP.

Systematic Reviews

Back Schools

Cochrane Collaboration

An SR was conducted in 1999 and updated in 2003 by the Cochrane Collaboration on back schools for nonspecific low back pain.29–31 A total of 19 RCTs were identified, including 12 studies of CLBP patients, 4 studies of acute/subacute LBP patients, and 3 of mixed populations.4,18,20,32–47 The authors concluded that the methodologic quality of studies was low, and there is conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of back schools for acute/subacute LBP. However, moderate evidence exists for the effectiveness of back schools compared with other treatments for pain and functional status in the short and intermediate term among patients with CLBP. Furthermore, there is moderate evidence that back schools in an occupational setting are more effective than other treatments, placebo, or waiting list controls for pain, functional status, and return to work in the short and intermediate term for patients with CLBP. This review did not discuss results specific to radicular or axial pain.

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR was conducted in 2006 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians CPG committee on nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic LBP.48 That review identified three SRs on back schools,30,31,49,50 including the Cochrane review previously described. The three SRs included 31 unique trials. The review found the conclusions of the SRs were consistent, that back schools have not been shown to be effective in acute, subacute, or chronic LBP. However, some benefits were observed in trials of back schools in occupational settings and in more intensive programs based on the original Swedish Back School.

Other

Brox and colleagues conducted an SR in 2008 examining back schools, brief education, and fear avoidance training for CLBP.51 A total of 23 RCTs were included, of which 8 pertained to back schools. This SR concluded that there is conflicting evidence for back schools related to pain and disability improvement compared with waiting list, no intervention, and placebo. This SR also concluded that there was limited evidence for back schools related to pain and disability improvement versus usual care, exercise, or a cognitive behavioral back school.

Fear Avoidance Training

Other Systematic Reviews

In an SR published in 200851 on fear avoidance training in CLBP (>12 weeks), three RCTs in four reports were included.24,52–54 RCTs involving fear avoidance training as a separate intervention or as part of a rehabilitation program were included. Based on one large high-quality trial, the authors of the SR concluded that there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of fear avoidance training in primary care and physical therapy compared with usual care.52 Based on the other two trials, there is moderate evidence that fear avoidance training in a rehabilitation program is not more effective than spinal fusion.

Another review identified one RCT that found fear avoidance training in a rehabilitation program was more effective than usual care in reducing disability in acute LBP patients with high fear avoidance beliefs, but counterproductive for patients with low fear avoidance beliefs.55–56

Findings from the above SRs are summarized in Table 7-2.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Relevant RCTs were identified from the SRs summarized above, although not all were included. An electronic search of medical databases was also conducted to identify additional RCTs not previously summarized in SRs. Studies in which a majority of participants had symptoms for less than 12 weeks were excluded, as were studies related to CLBP with a specific etiology (e.g., spondylolisthesis or postoperative pain). Back schools were included when given to groups of patients by a paramedical or physical therapist (PT) or medical specialist and when the back schools constituted the main part of the intervention. Fear avoidance training was included when the training was a separate intervention or part of a rehabilitation program. In addition, pain-related fear and beliefs about avoidance behavior were measured before and after the intervention. Two authors independently assessed the methodologic quality of each study using 10 criteria proposed by the Cochrane Back Review Group (CBRG), awarding 1 point for each condition (5 or more was considered of higher quality).57

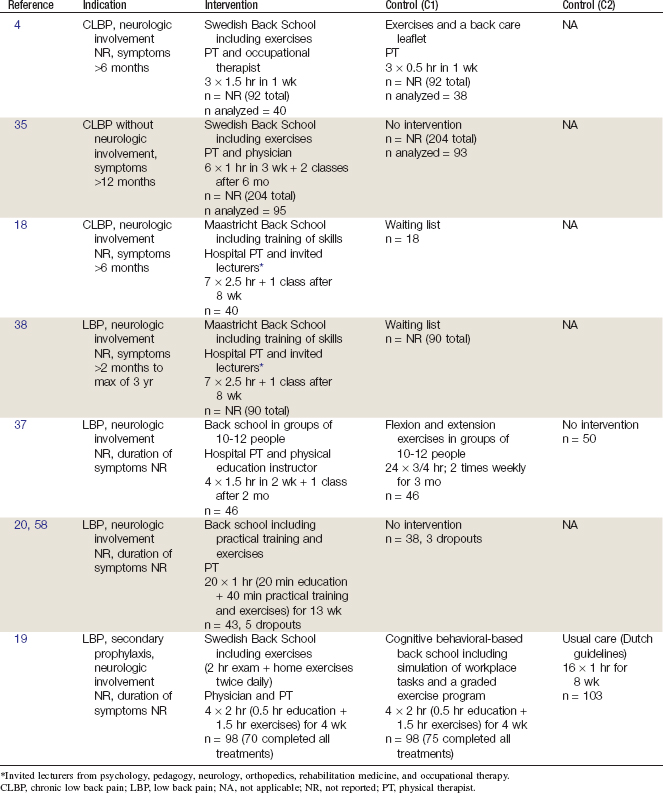

Back Schools

Seven RCTs and eight study reports related to those RCTs were identified.4,18-20,35,37-38,58 Their methods are summarized in Table 7-3. Their results are briefly described here.

Klaber Moffett and colleagues4 performed an RCT including CLBP patients from a hospital outpatient orthopedic clinic in the United Kingdom. In order to be included, participants had to be between ages 18 and 67 and have LBP lasting longer than 6 months. Those who had a history of spinal surgery, concurrent physical therapy treatments, and evidence of underlying disease, such as fracture, ankylosing spondylitis, or multiple myeloma, were excluded. Two patients who were unable to understand the treatment program and complete the questionnaires were also excluded. A total of 92 patients were enrolled; 40 participants in the intervention and 38 in the control groups were included in analysis. Participants in the intervention group received three 1.5-hour sessions in 1 week of Swedish Back School with exercise with a PT and occupational therapist (OT), while the control group received three 0.5-hour sessions in 1 week of the same exercises used in the intervention group. The control groups also received handouts of exercises and back care leaflets. After 16 weeks, a larger decrease in pain scores (visual analog scale [VAS]) compared with baseline were observed among the Swedish Back School group, but the difference was not statistically significant. After 16 weeks, there was also a decrease in functional disability scores (Oswestry Disability Index [ODI]) compared with baseline among the Swedish Back School participants, while scores among the exercise-only group remained similar compared with baseline. However, this difference was not statistically significant. This study was considered of higher quality.

Hurri35 conducted an RCT of female employees with CLBP in Finland. Participants with idiopathic LBP lasting at least 12 months and with LBP present on at least 1 day each week during the preceding month and/or activity of daily living (ADL) limitations were included. Those with rheumatoid arthritis or other systemic connective tissue disease or a history of back surgery were excluded. A total of 204 females were enrolled; 95 in the intervention group and 93 in the control group were included in analysis. The intervention included 1-hour sessions of Swedish Back School 6 times in 3 weeks and there was no intervention in the control group, but control participants received written materials of the back school. Pain was measured using a VAS and the Low Back Pain Index. After 12 months, there was a statistically significant improvement in VAS pain scores in the intervention group but not the control group compared with baseline. With the Low Back Pain Index, there were significant improvements in pain scores at 12 months compared with baseline in both intervention and control groups. There were no significant changes in functional status (ODI) at 12 months compared with baseline in either group. There were no significant differences between the two groups in pain or functional status. This study was considered of lower quality.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree