Back and lower extremity pain

Back and lower extremity pain

Introduction

The back and lower extremities are areas commonly affected by chronic pain. Lower extremity pain may occur in conjunction with back pain (as radicular, referred, or radiating pain) or as isolated musculoskeletal or neuropathic pain. Back pain with or without associated lower extremity pain occurs frequently and is often disabling. Using data from two large, national surveys in the United States, low back pain during the preceding 3 months was endorsed by one in four adults ≥18 years old and one in three adults after age 45

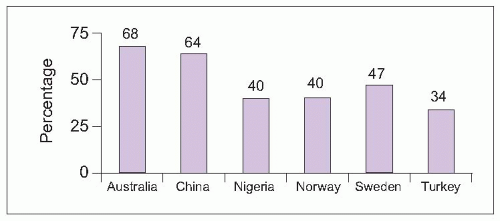

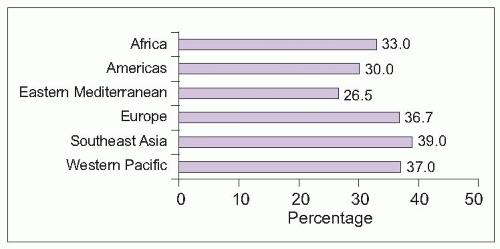

1. The prevalence of back pain varies by region, with typically higher prevalence among developed countries (

5.1)

2,

3,

4,

5,

6.

Most episodes of acute back pain resolve, with the greatest reduction in pain expected during the first 3 weeks

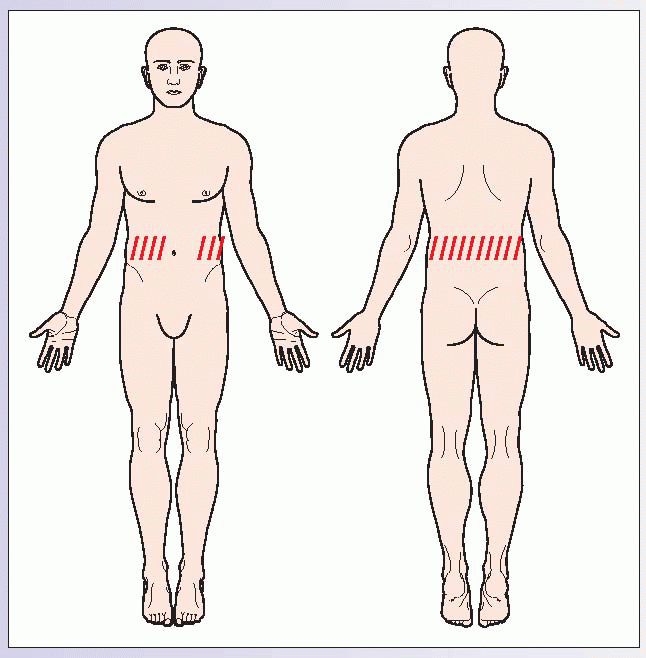

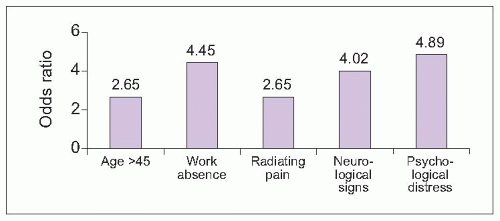

7. Pain becomes chronic for about one in four patients. Persistent back pain can be predicted by patient demographics, physical examination, and psychological distress (

5.2).

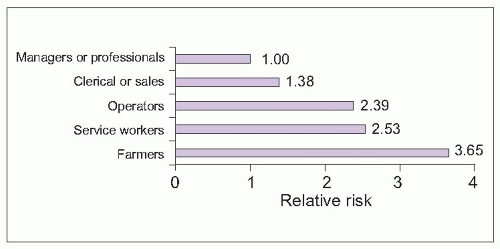

Occupation is another important risk factor for chronic back pain, with 37% of low back pain attributable worldwide to occupational factors

8. Occupational contribution is highest in Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Western Pacific (

5.3). Risk varies among occupation types, with lowest risk in managerial and professional jobs and highest risk among farmers (

5.4).

Assessing back and lower extremity pain

Chronic back pain is commonly caused by musculoskeletal or neurological abnormalities. Other medical conditions, including vascular, gastrointestinal, and gynecological pathology may also result in back pain (

Tables 5.1, 5.2). Therefore, the physical examination must include a general medical screening, as well as abdominal and gynecologic evaluations.

Signs and symptoms help differentiate among common causes of back pain. Neurological symptoms or deficits suggest additional evaluations for spinal, root, or peripheral nerve abnormalities. Attention to factors that aggravate or relieve pain, localization of pain to the back or radiation to the lower extremity, and response to postural changes can help distinguish common myofascial, mechanical, inflammatory, radicular, and stenotic pain syndromes in the lumbar spine (

Table 5.3).

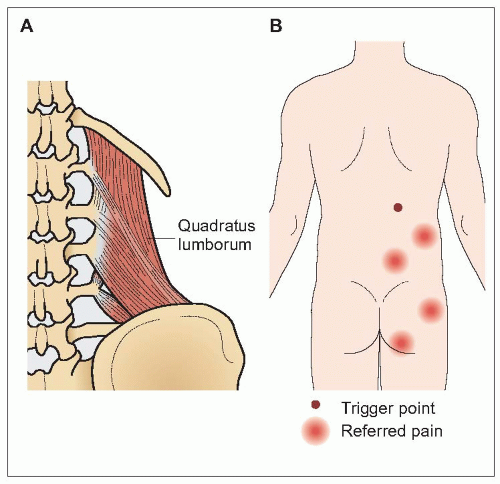

Myofascial lumbar pain

Pain of the muscles and surrounding soft tissues is termed myofascial pain. Myofascial pain is characterized by localized areas of muscle spasm and discrete points of tenderness within tight muscles, called trigger points. Trigger points are locally tender (latent trigger points) and may refer pain in predictable patterns (active trigger points) that assist in diagnosis. Myofascial pain affecting the quadratus lumborum muscle, quadratus lumborum syndrome, is one of the most common causes of low back pain. The quadratus lumborum muscles on either side of the

spine contract to cause lateral bending (

5.5). Pain typically occurs in the small of the back and may be referred into the buttocks.

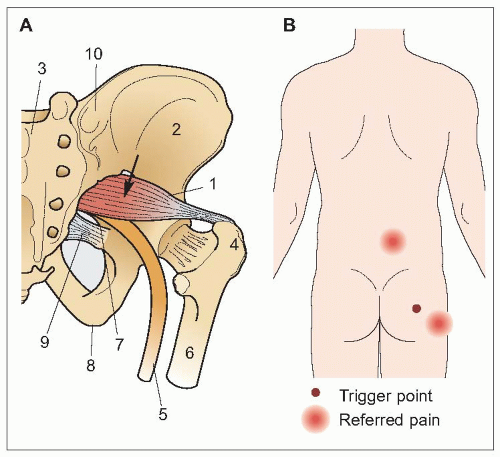

Piriformis syndrome is another common myofascial pain condition. The piriformis muscle connects the hip to the greater trochanter, resulting in hip stability and allowing external rotation (

5.6). Pain usually occurs in the lateral buttocks with referral to the lower back and hip.

Mechanical and inflammatory lumbar pain

Restrictions of both active and passive motion in the joints in the back suggest mechanical or inflammatory pain. Pain and restrictions in joint movement in the lower back are usually caused by mechanical pain, such as degenerative arthritis. Less commonly, chronic low back pain and restricted movement may be caused by an inflammatory spondyloarthropathy. Pain and stiffness are characteristically worse later in the day with mechanical pain, aggravated by activity or exercise. Inflammatory pain and stiffness, conversely, are worse in the early morning or after resting in bed, improving with activity.

Inflammatory spondyloarthritides include ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis (Reiter’s syndrome), and inflammatory bowel-related arthritis. While there are no specific tests for spondyloarthritides, patients often have blood tests showing elevation of inflammatory markers, like

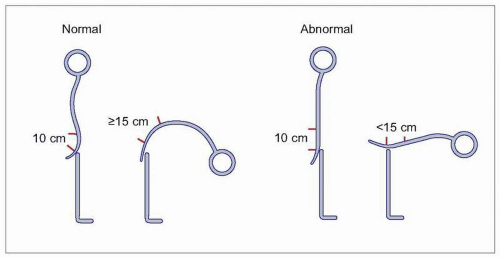

CRP, anemia of chronic disease, and the absence of rheumatoid factor. A modified Schober’s test is a nonspecific measure of reduced spine mobility (

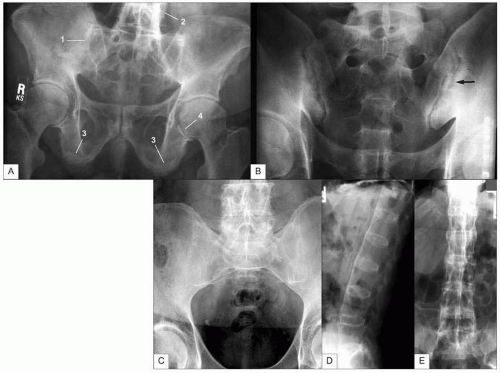

5.7). The most common spondyloarthritis is ankylosing spondylitis, which typically becomes symptomatic in young adulthood. Patients experience inflammatory changes in the spine and sacroiliac joints, with eventual fusion of the spine. While X-ray changes may be dramatic, patients typically display clinical symptoms for 5-10 years before radiographic changes are seen (

5.8).

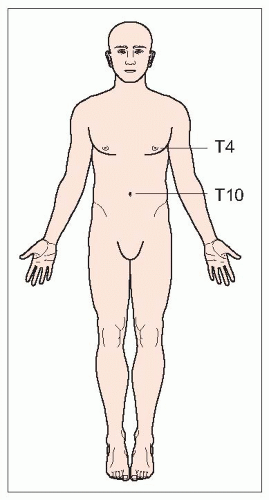

Neurological lumbar and lower extremity pain

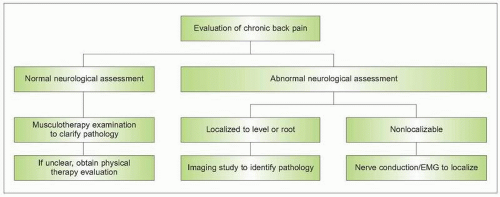

A neurological assessment of back pain patients is necessary to help differentiate musculoskeletal from neurological causes of chronic back pain (

5.9). Neurological symptoms or signs suggesting radiculopathy or myelopathy, such as pain with straight leg raise testing, loss of motor strength or reflexes, and sensory loss or allodynia, warrant additional testing. Patients with motor or sensory findings suggesting a localizable spinal level or nerve root should be evaluated with a targeted imaging study, such as

CT or

MRI. When a particular level or root cannot be localized, nerve conduction studies with

EMG should be considered.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access