Awake Craniotomy Can Be Done Humanely

Alexis Bilbo MD

Laurel E. Moore MD

It’s 7:00 AM when you learn that your supposedly routine craniotomy for tumor resection is actually an awake craniotomy because of the proximity of the tumor to Broca’s area. The patient has been coached by the surgeon, but the family is agitated and fails to understand why anyone would need to have their head opened while awake. What do you need to prepare the room for anesthesia, and what do you say to the family to reassure them?

Awake craniotomies are relatively uncommon procedures that are generally performed in large-volume neurosurgical centers. The usual indication is to facilitate intraoperative electrocorticography to map eloquent brain regions involved in speech, motor, and sensory function in order to minimize neurologic injury to these critical regions during tumor resection. The main objectives of the anesthetic employed for awake craniotomies are to (a) minimize patient discomfort associated with painful portions of the procedure and prolonged restriction of movement, (b) ensure patient responsiveness and compliance during phases of the procedure that require assessment of speech or motor function, and (c) produce minimal inhibition of spontaneous seizure activity. These objectives are achieved by using a variety of techniques that range from minimal sedation to asleep-awake-asleep techniques using a laryngeal mask airway (LMA). There are many important considerations when performing anesthesia for an awake craniotomy. These include pain control, airway management, the possibility of hypoventilation in the setting of increased intracranial pressure, the onset of seizures, the possible complication of venous air embolism (VAE), and patient selection.

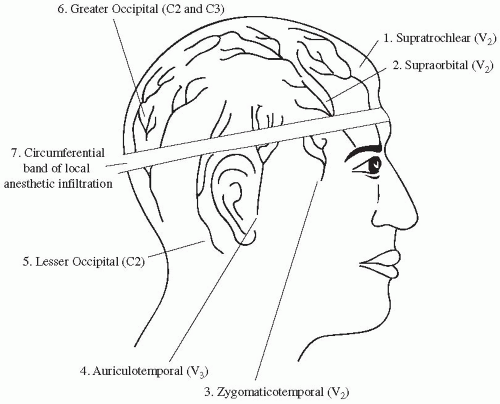

Pain control is critical to the care of patients undergoing awake craniotomies. Certain parts of the procedure, such as pin fixation of the head, temporalis muscle dissection, and traction on the dura close to the middle meningeal artery territory can be especially painful. In most institutions, pain control is accomplished with a combination of narcotics and regional anesthesia. Narcotics can be administered as a bolus or as an infusion. The narcotics used should be short acting with minimal effects on electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring. Fentanyl and remifentanil are appropriate choices. Also, a scalp block is necessary to control pain. Scalp blocks are performed using a 22-gauge intradermal needle with circumferential injection, following a line from the glabella to the occiput and dividing it into four parts

at the intersection of the sagittal and frontal planes (Fig. 136.1). Mayfield pin sites generally require supplementation and should be done in conjunction with the neurosurgeon placing the head holder. The local anesthetic used for injection should have a prompt onset of action, provide analgesia for a significant period of time, and not interfere with electrocorticography. Lidocaine and bupivacaine may be used in combination to achieve rapid onset, long duration and minimal toxicity. Because the scalp block requires a large volume of local anesthetic (as much as 60 cc), it is important for the anesthesiologist to be vigilant in calculating dosages of local anesthetics and monitoring for toxicity. The addition of a third drug such as chloroprocaine or ropivacaine may be necessary to safely achieve the necessary volume of local anesthetic. Avoidance of local anesthetic toxicity is obviously critical in patients immobilized in a Mayfield head holder. It is also important to realize that even with a perfect scalp block and in the absence of somatic pain, many patients will still have a vague (or even severe) headache that will require opioid supplementation.

at the intersection of the sagittal and frontal planes (Fig. 136.1). Mayfield pin sites generally require supplementation and should be done in conjunction with the neurosurgeon placing the head holder. The local anesthetic used for injection should have a prompt onset of action, provide analgesia for a significant period of time, and not interfere with electrocorticography. Lidocaine and bupivacaine may be used in combination to achieve rapid onset, long duration and minimal toxicity. Because the scalp block requires a large volume of local anesthetic (as much as 60 cc), it is important for the anesthesiologist to be vigilant in calculating dosages of local anesthetics and monitoring for toxicity. The addition of a third drug such as chloroprocaine or ropivacaine may be necessary to safely achieve the necessary volume of local anesthetic. Avoidance of local anesthetic toxicity is obviously critical in patients immobilized in a Mayfield head holder. It is also important to realize that even with a perfect scalp block and in the absence of somatic pain, many patients will still have a vague (or even severe) headache that will require opioid supplementation.

FIGURE 136.1. Schematic anterior and posterior view of the scalp.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|