Chapter 6 Assessment strategies and selected interventions

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

• Muscle tension/contraction headache: This headache type includes referred pain from trigger point activity, nerve impingement, muscle tension, connective tissue changes, and muscle guarding. Pain is experienced as pressure from the outside of the head pushing in and may feel like a tight band around the head. This headache type is effectively managed with massage.

• Vascular headache: In general the vascular or fluid pressure headache type includes sinus headache, hormone, migraine, cluster, caffeine withdrawal, and toxic headache. Pain is experienced as ache/pressure from the inside of the head pushing out. The head may feel like it will blow up. This headache type is difficult to manage with massage but general pain management strategies (see Chapter 4) can help and massage can address accompanying muscle tension-type headache.

THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

• What firing sequences are abnormal?

• What has happened, and/or what is the patient doing, to aggravate these changes?

Assessing pain

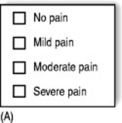

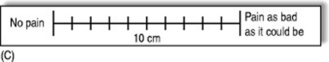

Verbal rating scale (VRS)

The simplest measuring device, the verbal rating scale (Figure 6.1A), records on paper or a computer what a patient reports – whether there is ‘no pain’, ‘mild pain’, ‘moderate pain’, or ‘severe pain’.

Numerical rating scale (NRS)

A numerical rating scale (Figure 6.1B) uses a series of numbers (zero to 100, or zero to 10): no pain would equal zero; worst pain possible would equal the highest number on the scale. The patient is asked to apply a numerical value to the pain and this is recorded along with the date.

Visual analog scale (VAS)

This widely used method (Figure 6.1C) consists of a 10-centimeter line drawn on paper, with marks at each end and at each centimeter. The zero end of the line equals no pain at all; the 10-centimeter end equals the worst pain possible. The patient marks the line at the level of their pain.

Questionnaires

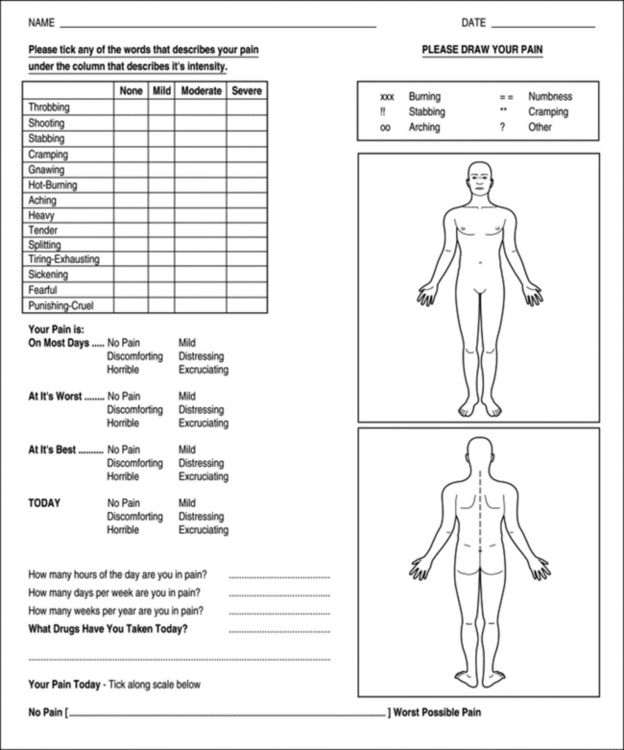

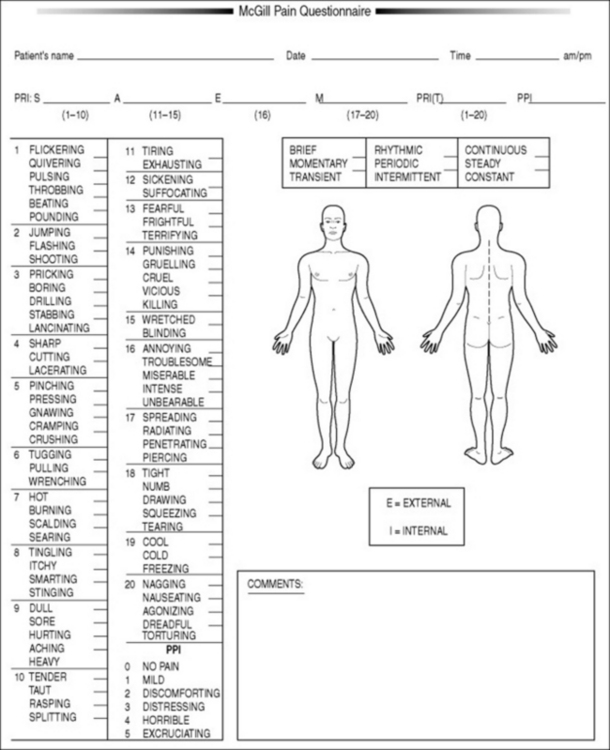

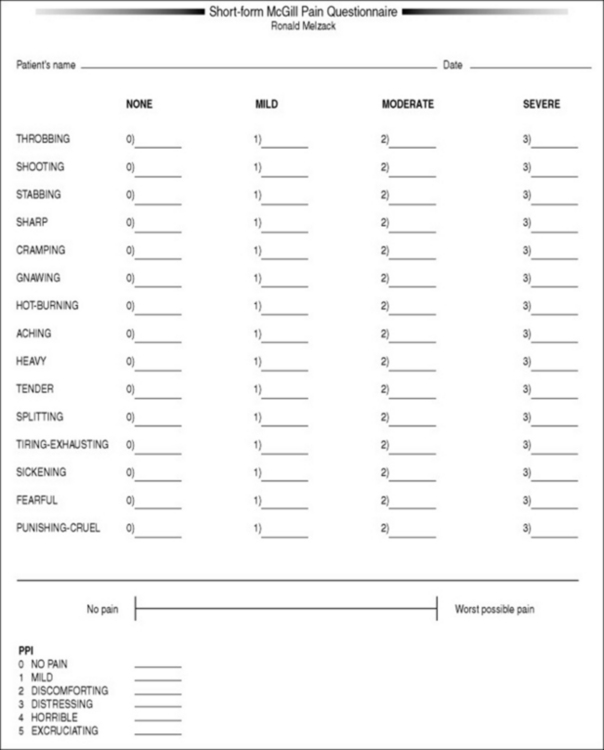

A variety of questionnaires exist, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire (Figure 6.2) and the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (Figure 6.3). The shorter version lists a number of words that describe pain (such as throbbing, shooting, stabbing, heavy, sickening, fearful).

Figure 6.2 McGill Pain Questionnaire. The descriptors fall into four major groups: sensory, 1–10; affective, 11–15; evaluative, 16; and miscellaneous, 17–20. The rank value for each descriptor is based on its position in the word set. The sum of the rank values is the pain rating index (PRI). The present pain intensity (PPI) is based on a scale of 0–5.

(Reproduced with permission from Melzack 1975.)

Figure 6.3 The Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Descriptors 1–11 represent the sensory dimension of pain experience and 12–15 represent the affective dimension. Each descriptor is ranked on an intensity scale of 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe. The present pain intensity (PPI) of the standard long-form McGill Pain Questionnaire and the visual analog scale are also included to provide overall pain intensity scores.

(Reproduced with permission from Melzack 1987.)

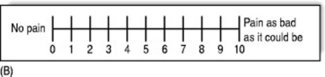

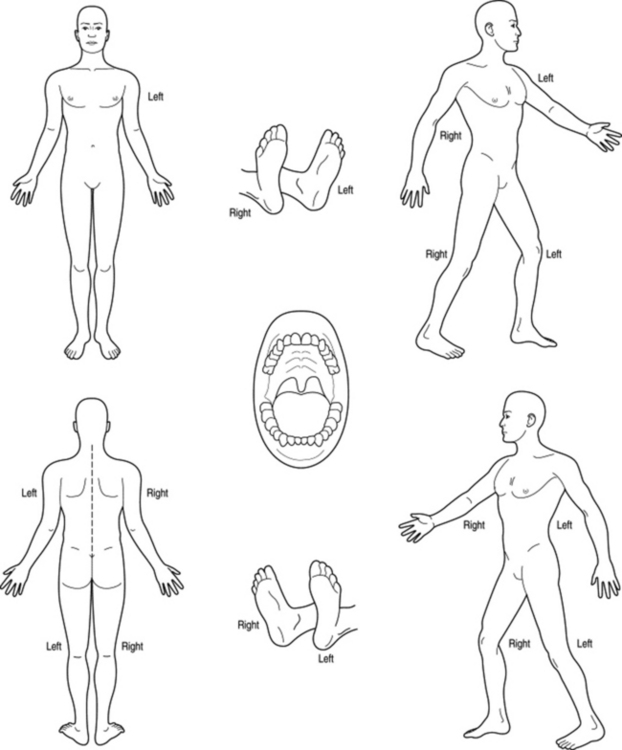

Pain drawings

It can be useful for the patient to color the areas of their pain on a simple outline of the human body using a red pencil (Figure 6.4A). The patient should write single-word descriptions of the pain in different areas (e.g., throbbing, aching, etc.), or a simple code can be used, for example: xx = burning pain, !! = stabbing pain, oo = aching, and so on. This record of both the location and the nature of the person’s pain can be compared with similar records at future visits.

A single sheet of paper can easily contain a VAS and a shortened McGill Questionnaire, as well as a series of simple questions such as those illustrated in Figure 6.4B.

Pain threshold

How can a person learn to apply a particular amount of pressure, and no more? It has been shown that, using simple technology (such as bathroom scales), physical therapy students can be taught to accurately produce specific degrees of pressure on request. Students are tested applying pressure to lumbar muscles. After training, using bathroom scales, the students can usually apply precise amounts of pressure on request (Keating et al 1993).

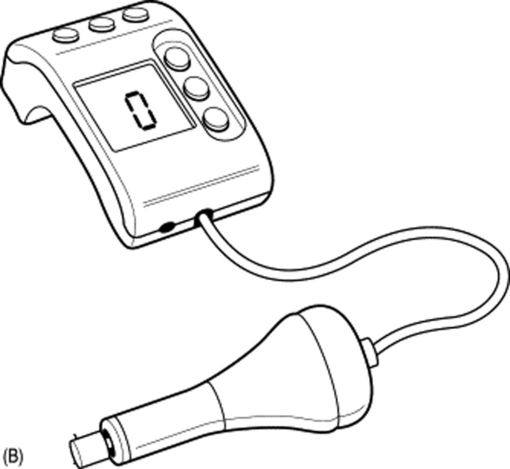

Algometer

A basic algometer is a hand-held, spring-loaded, rubber-tipped, pressure-measuring device (Figure 6.5A) that offers a means of achieving standardized pressure application.

Using an algometer, sufficient pressure to produce pain is applied to preselected points, at a precise 90-degree angle to the skin. The measurement is taken when pain is reported. An electronic version of this type of algometer (Figure 6.5B) allows recording of pressures applied; however, these forms of algometer are used independently of actual treatment to obtain feedback from the patient (e.g., to register the pressure being used when pain levels reach tolerance).

A variety of other algometer designs exist, including a sophisticated version that is attached to the thumb or finger with a lead running to an electronic sensor that is itself connected to a computer (Figure 6.5C). This gives very precise readouts of the amount of pressure being applied by the finger or thumb during treatment.

Baldry (1993) suggests that algometers should be used to measure the degree of pressure required to produce symptoms ‘before and after deactivation of a trigger point, because when treatment is successful, the pressure threshold over the trigger point increases’.

Crossed syndrome patterns (Box 6.1)

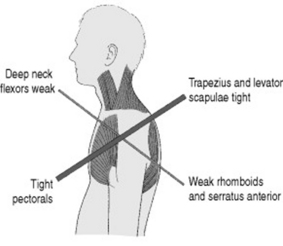

As compensation occurs due to overuse, misuse, and disuse of muscles of the head and neck, some muscles become overworked, shortened, and restricted, with others becoming inhibited and weak, and body-wide postural changes take place that have been characterized as ‘crossed syndromes’ (Lewit 1999a). These crossed patterns demonstrate the imbalances that occur as antagonists become inhibited due to the overactivity of specific postural muscles.

Box 6.1 Crossed syndrome patterns

Among the commonest bodywide stress influences are postural patterns such as the upper and lower crossed syndromes (Janda 1996).

UPPER CROSSED SYNDROME PATTERN

The upper crossed syndrome involves a round-shouldered, chin-poking, slumped posture that crowds the thorax and prevents normal breathing (Figure 6.6).

The effect on muscles of the temporomandibular joint and cervical spine is a cause of muscle-contraction headache. One of the main tasks in rehabilitation of such pain and dysfunction is to normalize these imbalances, to release and stretch whatever is over-short and tight, and to encourage tone in those muscles that have become inhibited and weakened (Liebenson 1996).

In the upper crossed syndrome pattern we see how the deep neck flexors and the lower fixators of the shoulder (serratus anterior, lower and middle trapezius) have weakened (and possibly lengthened), while their antagonists the upper trapezius, levator scapulae and the pectorals will have shortened and tightened. Not shown in Figure 6.6, but also short and tight, are the cervical extensor muscles, the suboccipitals, and the rotator cuff muscles of the shoulder.

In the lower crossed pattern, which is often found in conjunction with the upper crossed pattern, we find that the abdominal muscles have weakened, as have the gluteals, and at the same time psoas and erector spinae will have shortened and tightened. Not shown in Figure 6.7, but also short and tight, are tensor fascia lata, piriformis, quadratus lumborum, hamstrings, and latissimus dorsi.

Muscle function

Postural and phasic muscles

There are basically two types of muscle in the body – those that have stabilization as their main task, and those that have movement as their main task (Engel & Banker 1986, Woo & Buckwater 1987). These are known, in one of the many classification systems (Janda 1982), as:

It is not within the scope of this book to provide detailed physiologic descriptions of the differences between these muscle types, but it is important to know that:

• all muscles contain both types of fiber (Type I and Type II) but the predominance of one type over the other determines the nature of that particular muscle

• postural muscles have very low stores of energy-supplying glycogen but carry high concentrations of myoglobulin and mitochondria. These fibers fatigue slowly and are mainly involved in postural and stabilizing tasks, and when stressed (overused, underused, traumatized) tend to shorten over time

• phasic muscles contract more rapidly than postural fibers, have variable but reduced resistance to fatigue, and when stressed (overused, underused, traumatized) tend to weaken and sometimes to lengthen over time

• evidence exists of the potential for adaptability of muscle fibers. For example, slow twitch can convert to fast twitch, and vice versa, depending upon the patterns of use to which they are put and the stresses they endure (Lin et al 1994). An example of this involves the scalene muscles, which Lewit (1999b) confirms can be classified as either postural or phasic. If stressed (as in asthma), the scalenes will change from phasic to become postural muscles

• trigger points can form in either type of muscle in response to local situations of stress

• postural muscles are those muscles that shorten in response to dysfunction and include:

• phasic muscles are those muscles that weaken in response to dysfunction (i.e., are inhibited) and include:

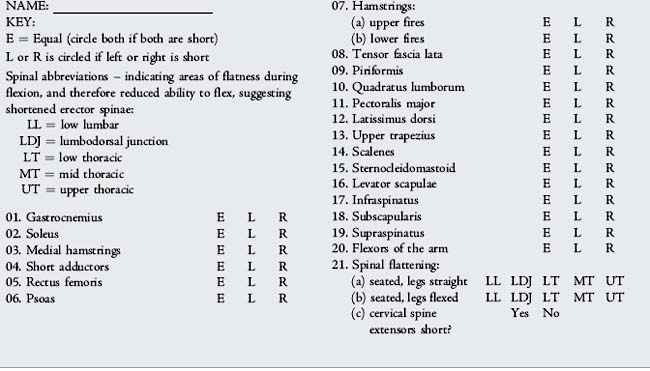

Box 6.2 is provided to chart changes (shortening) in the main postural muscles.

Palpation skills

The ability of a therapist to regularly and accurately locate and identify somatic landmarks, and changes in function, lies at the heart of palpation skills.

Box 6.2 Postural muscle assessment sequence

Greenman (1996) has summarized the five objectives of palpation. You, the therapist, should be able to:

• detect abnormal tissue texture

• evaluate symmetry in the position of structures, both physically and visually

• detect and assess variations in range and quality of movement during the range, as well as the quality of the end of the range of any movement (‘end feel’)

• sense the position in space of yourself and the person being palpated

• detect and evaluate change, whether this is improving or worsening as time passes.