Assessment of Pain

Alyssa A. LeBel

When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge of it is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely, in your thoughts, advanced to the stage of science.

—William Thompson Lord Kelvin, 1824–1907

Pain is a complex multidimensional symptom determined not only by tissue injury and nociception but also by previous pain experience, personal beliefs, affect, motivation, environment, and, at times, pending litigation. There is no objective measurement of pain. Self-report is the most valid measure of the individual experience of pain. The pain history is key to the assessment of pain and includes the patient’s description of pain intensity, quality, location, timing, and duration, as well as ameliorating and exacerbating conditions. Frequently, pain cannot be seen, defined, or felt by the physician, and the physician must assess the pain from a combination of factors. The most important of these factors is the patient’s report of the pain, but other factors such as personality and culture, psychological status, the existence of secondary gain, and the possibility of drug-seeking behavior should also be considered. Reports of pain may not correlate with the degree of disability or findings on physical examination. However, it is important to remember that to the patients and their families, distress, suffering, and pain behaviors are often not distinguished from the pain itself.

Diagnosis and measurement of acute pain require frequent and consistent assessment as part of daily clinical care to ensure rapid titration of therapy and preemptive interventions. Chronic pain is often more diagnostically challenging than acute pain, but no less compelling. Application of a structured history and

comprehensive physical examination will define treatable problems and identify complicating factors. Somatic, visceral, neuropathic, or combined pain problems suggest specific diagnoses and interventions. An understanding of pain pathophysiology guides rational and appropriate treatment.

comprehensive physical examination will define treatable problems and identify complicating factors. Somatic, visceral, neuropathic, or combined pain problems suggest specific diagnoses and interventions. An understanding of pain pathophysiology guides rational and appropriate treatment.

I. PAIN HISTORY

The general medical history may contribute considerably and is always included as part of the pain assessment. This is described in Chapter 4. The specific pain history includes three main issues—intensity, location, and pathophysiology. The following questions help define these issues:

What is the time course of the pain?

Where is the pain?

What is the intensity of the pain?

What factors relieve or exacerbate the pain?

What are the possible generators of the pain?

1. Pain Assessment Tools

As previously stated, pain cannot be objectively measured. The intensity of pain is one of the most difficult and perhaps frustrating characteristics of pain to pinpoint. Several tests and scales are available. Some of the more commonly used tools are the following:

(i) Unidimensional Self-report Scales

In practice, self-report scales serve as very simple, useful, and valid methods for assessing and monitoring patients’ pain.

VERBAL DESCRIPTOR SCALES.

The patient is asked to describe his or her pain by choosing from a list of adjectives that reflect gradations of pain intensity. The five-word scale consists of mild, discomforting, distressing, horrible, and excruciating. Disadvantages of this scale include limited selection of descriptors and the fact that patients tend to select moderate descriptors rather than the extremes.

VERBAL NUMERIC RATING SCALES.

These are the most simple and frequently used scales. On a numeric scale (most commonly 0 to 10, with 0 being “no pain” and 10 “the worst pain imaginable”), the patient picks a number to describe the pain. Advantages of numeric scales are their simplicity, reproducibility, easy comprehensibility, and sensitivity to small changes in pain. Children as young as 5 years old, who are able to count and have some concept of numbers (e.g., “8 is larger than 4”), can use this scale.

VISUAL ANALOG SCALES.

Visual analog scales (VSA) are similar to the verbal numeric rating scales, except that the patient marks on a measured line, one end of which is labeled “no pain” and the other end “worst pain imaginable,” where the pain falls. Visual scales are more valid for research purposes, but are used less clinically because they are more time-consuming to conduct than verbal scales and require motor control.

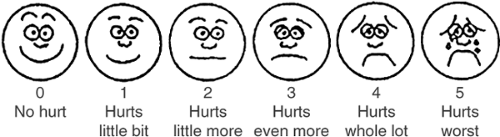

FACES PAIN RATING SCALE.

Evaluating pain in children can be very difficult because of the child’s inability to describe pain or to understand pain assessment forms. This scale depicts six sketches

of facial features, each with a numeric value, 0 to 5, ranging from a happy, smiling face to a sad, teary face (see Fig. 1). To extrapolate this scale to the VSA, the value chosen is multiplied by two. This scale may also be beneficial for mentally impaired patients. Average children as young as 3 years can reliably use this scale.

of facial features, each with a numeric value, 0 to 5, ranging from a happy, smiling face to a sad, teary face (see Fig. 1). To extrapolate this scale to the VSA, the value chosen is multiplied by two. This scale may also be beneficial for mentally impaired patients. Average children as young as 3 years can reliably use this scale.

(ii) Multiple Dimension Instruments

These instruments provide more complex information about the patient’s pain. They are especially useful for assessment of chronic pain. Because they are time consuming, they are most frequently used in outpatient and research settings.

MCGILL PAIN QUESTIONNAIRE.

McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ) is the most frequently used multidimensional test. Descriptive words from three major dimensions of pain (i.e., sensory, affective, and evaluative) are further subdivided into 20 subclasses, each containing words of varying degrees. Three scores are obtained, one for each dimension, and a total score is calculated. Studies have shown the MPQ to be a reliable instrument in clinical research.

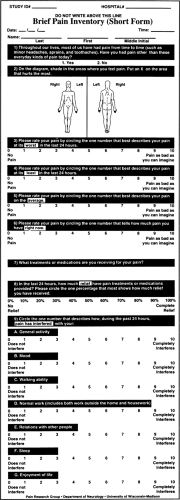

BRIEF PAIN INVENTORY.

In brief pain inventory (BPI), patients are asked to rate the severity of their pain at its “worst,” “least,” or “average,” within the past 24 hours and at the time the rating is done. The inventory also requires the patients to represent the location of their pain on a schematic diagram of the body. The BPI correlates with the scores of activity, sleep, and social interactions. It is cross-cultural and a useful method for clinical studies (see Fig. 2).

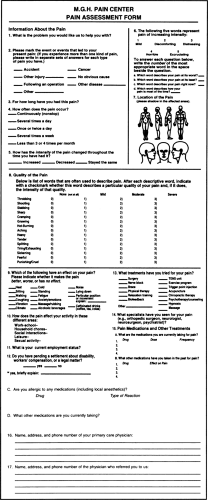

MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL PAIN CENTER PAIN ASSESSMENT FORM.

Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Pain Center pain assessment form (see Fig. 3) combines many of the foregoing assessment instruments and is given to all patients on initial consultations at the MGH Pain Center. It elicits information about pain intensity, its location (body diagram), quality of pain, therapies tried, and past and present medications. It takes 10 to 15 minutes to complete and is an extremely valuable instrument. Its disadvantages are that it is time-consuming to complete and is not applicable if there are language constraints.

(iii) Pain Diaries

A diary of a patient’s pain is useful in evaluating the relation between pain and daily activity. Pain can be described using the numeric rating scale, during activities such as walking, standing, sitting, and routine chores. The evaluation can be done on an hourly basis. Use of medication and alcohol, and emotional responses of the patient and family may also be recorded. Pain diaries may reflect a patient’s pain more accurately than a retrospective description that may significantly over- or underestimate pain.

2. Pain Location

The location and distribution of pain are extremely important characteristics that help in understanding the pathophysiology of the pain complaint. Body diagrams, found in some of the assessment instruments, can prove very useful. Although the clinician can view the patient’s perception of the topographic area of pain, the patient may show psychological distress either by poorly localizing the pain or by magnifying the pain to other areas of the body.

Is the pain localized or referred? Localized pain is pain confined to its site of origin, without radiation or migration. Referred pain usually arises from visceral or deep structures and radiates to other areas of the body. A classic example of referred pain is shoulder pain from phrenic nerve irritation (causes include liver metastases from pancreatic cancer) (see Table 1).

Is pain superficial/peripheral or visceral? Superficial pain, arising from tissues rich in nociceptors, such as skin, teeth, and mucous membranes, is easily localized and limited to the affected part of the body. Visceral pain arises from internal organs, which contain relatively few nociceptors. Visceral afferent information may converge with superficial afferent input at the spinal level, referring the perception of visceral pain to a distant dermatome. Visceral pain is diffuse and often poorly localized. In addition, it often has associated autonomic components such as diaphoresis, capillary vasodilation, hypertension, or tachycardia.

3. Pain Etiology

By taking a complete history and by answering the two questions described in preceding text (Is pain superficial/peripheral or visceral? Is the pain localized or referred?), the clinician can begin to formulate the etiology of the pain complaint. By doing so, the rest of the history, as well as the physical examination, can be tailored to systematically explore the aspects of pain, such as symptoms and physical signs, common to the particular type of pain in question.

Types of Pain

The various types of pain tend to present differently (e.g., nociceptive pain is associated with tissue injury due to trauma, surgery, inflammation or tumor; neuropathic pain is invariably associated with sensory change; and radicular pain is often associated with radiculopathy). History and physical examination help identify these differences. Because the different types of pain tend to respond to different treatments, the identification of

the pain type during pain assessment is important. Pain can be categorized as follows:

the pain type during pain assessment is important. Pain can be categorized as follows:

Figure 2. Brief pain inventory (see text). (Adapted from Zempsky WT, Schecter NL. What’s new in the management of pain in children. Ped Clin North Am 1989;36:823–836, with permission. |

Nociceptive—pain arising from activation of nociceptors; nociceptors are found in all tissues except the central nervous system (CNS); the pain is clinically proportional to the degree of activation of afferent pain fibers and can be acute or chronic (e.g., somatic pain, cancer pain, and postoperative pain).

Neuropathic—pain caused by nerve injury or disease, or by involvement of nerves in other disease processes such as tumor or inflammation; the pain may occur in the periphery or in the CNS

Sympathetically mediated—pain that is characterized at some point with evidence of edema, changes in skin blood flow, abnormal sudomotor activity in the region of pain, allodynia, hyperalgesia, or hyperpathia