CHAPTER 3 Assessment of Low Back Pain

Common low back pain (LBP) is a frequent complaint for which numerous health care providers are routinely consulted.1 While the management of common LBP can quickly become complicated, it is important to remember the basic goals of patients who seek care. First, patients wish to be reassured that despite any excruciating pain they may be feeling, their health is not in imminent danger. Patients may have waited weeks, months, or even years before consulting a clinician. It is quite possible that the severity or debilitating nature of their symptoms may have led them to imagine horrible scenarios about their cause. Although this is very rarely the case with common LBP, clinicians nevertheless need to conduct a thorough assessment to eliminate this remote possibility and demonstrate to the patient that their concerns are being heard and addressed.2,3

Second, patients wish to learn something about the general nature of their condition, including possibly a differential or working diagnosis. There are many diagnostic modalities available to clinicians that portend to facilitate this process, but an overreliance on such testing overlooks one of the fundamental principles of common LBP: its unclear and nonspecific origins.1,4 There is mounting evidence of overuse of diagnostic testing for LBP, especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).5 Wide regional disparities have also been noted in the use of MRI for common LBP in the United States. Not only are there substantial costs associated with MRI for LBP but there are also clinical consequences to their overuse.6,7

Studies have reported that patients with common LBP who are made aware of MRI findings, none of which were significant or revealed any serious spinal pathology, did not improve as rapidly as those who were not aware of the mostly minor anatomic variants noted on those reports.8 Even though clinicians may dismiss such inconsequential MRI findings, patients may not be so cavalier. Simply knowing that they have “abnormalities” in their lumbar spine that can be pointed to on an MRI scan may cloud their potential for quick recovery. A correlation has also been established between the rate of diagnostic testing such as MRI for common LBP and the rate of subsequent medical or surgical procedures aimed at correcting their findings, including epidural steroid injections and lumbar decompression or fusion.8 Whereas some of these procedures are in fact warranted when patients have serious spinal pathology or other accepted indications, in many instances they are not strictly necessary and may incur negative ramifications such as costs and harms.9–12

Recent Clinical Practice Guidelines

To balance the necessity of conducting a thorough clinical assessment of common LBP with the obligation that clinicians have to minimize the harm resulting from unnecessary diagnostic testing, it may be helpful to receive guidance from clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). Numerous evidence-based CPGs have been conducted to identify, evaluate, summarize, and synthesize the results of hundreds or even thousands of studies related to the assessment of common LBP. Such CPGs were developed specifically to help practicing clinicians make practical decisions about their patients, and are therefore considered important tools to the practice of evidence-based medicine.13–16 Although recommendations from CPGs are not intended to replace expert clinical judgment, they can enhance decision making by providing guidance for uncertain scenarios. Clinicians may also feel more confident about their clinical judgment when it is based on recommendations from well-conducted CPGs.

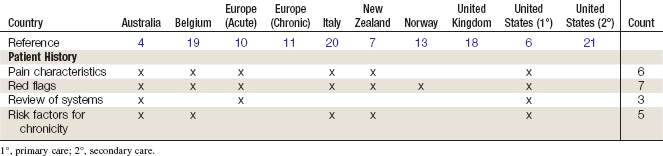

The findings from 10 CPGs sponsored by national organizations throughout the world and published in English during the past decade were compared and summarized to provide clinicians with an overview of the best available evidence to guide their assessment of patients with common LBP. An equal number of the CPGs summarized evidence related to acute LBP (i.e., less than 12 weeks) and chronic LBP (CLBP) (i.e., more than 12 weeks), using definitions recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group (CBRG).17 It was unclear why two of the CPGs reviewed defined CLBP as lasting more than only 4 to 6 weeks.6,18 Such temporal classifications are somewhat arbitrary, but they do facilitate comparison of recommendations when used consistently.18 It was also unclear why some CPGs excluded LBP with neurologic involvement from their scope when this presentation is found in a substantial proportion of patients with LBP.7 The results of these 10 CPGs are presented according to the stated goals of the assessment, rather than by diagnostic modality.

Goals of Assessment for Low Back Pain

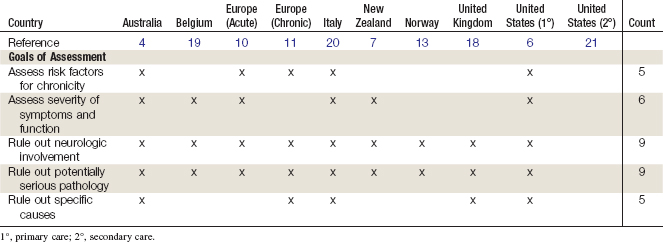

There was general agreement among the 10 recent CPGs reviewed that there are 5 main goals when conducting an assessment of LBP and that these goals can be considered sequentially, in that the findings from each goal can be pertinent to achieving the next goal. These five goals include (1) ruling out potentially serious spinal pathology,4,6,7,10,11,13,18–21 (2) ruling out specific causes of LBP,4,6,11,18,20 (3) ruling out substantial neurologic involvement,4,6,7,10,11,13,18–20 (4) evaluating the severity of symptoms and functional limitations,4,7,10,11,19,20 and (5) identifying risk factors for chronicity.4,6,10,11,22 Findings from the 10 recent CPGs that were pertinent to each of these goals are discussed below and summarized in Tables 3-1 and 3-2.

Ruling Out Potentially Serious Spinal Pathology

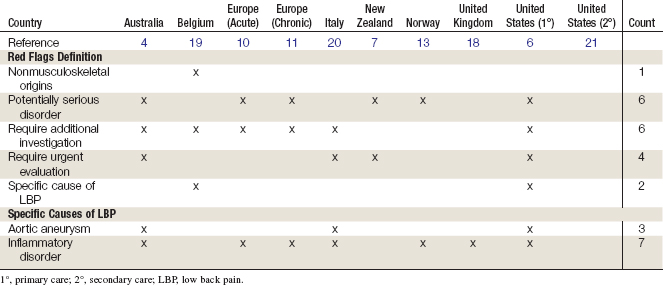

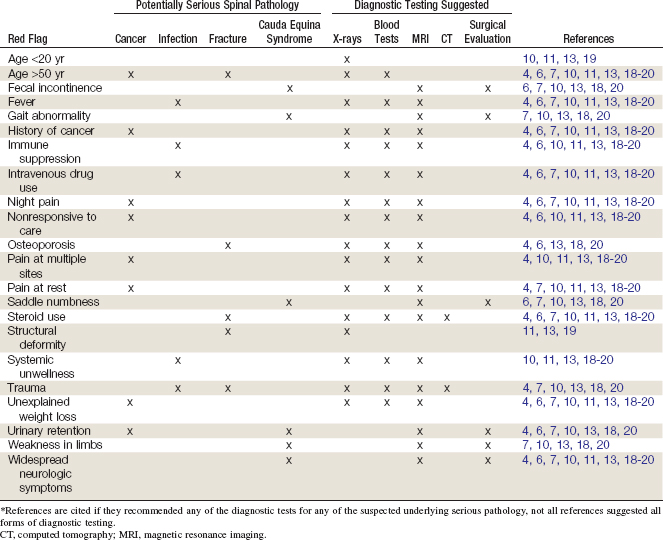

All CPGs discussed the possibility that symptoms of LBP—in very rare cases—could be due to potentially serious spinal pathology. It was generally suggested that clinicians screen such conditions by identifying items indicating the presence of potentially serious spinal pathology known as red flags which are signs, symptoms, or patient characteristics that may indicate the need for additional screening to eliminate the possibility of underlying medical conditions. The number of red flags for LBP specified in each CPG ranged from 7 to 17, with a mean of 11. Overall, 22 red flags were identified, the most common being age older than 50 years (n = 9), history of cancer (n = 9), and steroid use (n = 9); the least common were gait abnormality (n = 2) and weakness in limbs (n = 1). Of the 22 red flags, 8 were potentially associated with spinal cancer, 6 with cauda equina syndrome, 5 with spinal fracture, and 5 with spinal infection; one red flag (age older than 50 years) was associated with both cancer and fracture. One red flag (age younger than 20 years) was not reported as being associated with any specific serious spinal pathology. Findings from the 10 recent CPGs that were pertinent to serious pathology are summarized in Table 3-3.

Red flags suggesting spinal cancer included a history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, nonresponsiveness to care, night pain, pain at multiple sites, pain at rest, age older than 50 years, and urinary retention; x-ray studies and blood tests or MRI was suggested in those patients. Red flags suggesting cauda equina syndrome included fecal incontinence, gait abnormality, saddle numbness, urinary retention, weakness in limbs, and widespread neurologic symptoms; surgical evaluation or MRI was generally recommended in those patients. Red flags suggesting spinal fracture included age older than 50 years, osteoporosis, steroid use, structural deformity, and trauma; x-ray studies and blood tests or MRI/computed tomography (CT) was recommended in those patients. Red flags suggesting spinal infection included fever, immune suppression, intravenous drug use, systemic unwellness, and trauma (one CPG4 reported this); blood tests and x-ray studies or MRI was recommended in those patients. Findings from the 10 recent CPGs that were pertinent to red flags and serious spinal pathology are summarized in Table 3-4.