PD is an affliction of middle to late adult life, although 30% of patients report recognizable symptoms before the age of 50 years. In another 40%, the disease develops between the ages of 50 and 60 years, and the remainder is older than 60 years old at the time of diagnosis. The classic syndrome of parkinsonism includes

tremor at rest, rigidity, bradykinesia, masked face, stooped posture, and a

shuffling gait. Although tremor is the most obvious initial finding, it is absent in 20% of patients. PD may begin insidiously with vague,

aching pain in the limbs, neck, or back and with

decreased axial dexterity before tremor is noted.

Dysarthria may be an early feature;

dysphagia usually occurs later. The onset of PD, whether primarily with tremor, rigidity, or bradykinesia, is usually asymmetric (see

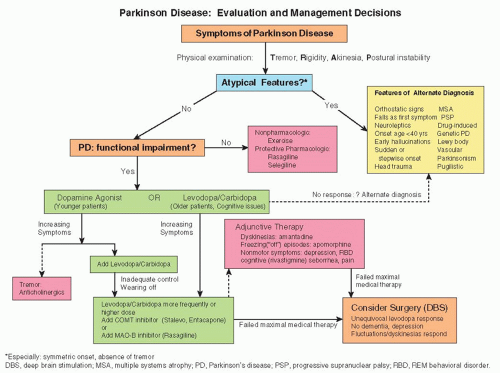

Fig. 174-1).

Subtler symptoms may also be noted, sometimes early.

Orthostatic hypotension suggests cardiac sympathetic denervation, which can be found in many patients and may cause neurocirculatory failure.

Micrographia (decrease in the caliber of handwriting), decrease in volume of the voice, and

anosmia are other subtle but characteristic manifestations.

Depression may be a feature of early disease. The estimated frequency of

dementia (which usually develops late) varies widely, but

cognitive impairment, including hallucinations and psychosis, develops in at least 15% to 20% of patients (some of whom are likely to have Lewy body disease; see

Chapter 169). However, dementia and psychosis are not inevitable, and remediable causes of changes in mental status always need to be sought.