Key Clinical Questions

What is the psychiatric differential diagnosis for patients with unexplained physical symptoms?

How can factitious disorder (Münchausen syndrome) be differentiated from malingering?

What is conversion disorder, and how is this different from factitious disorder?

What are the best practices in the care of patients with Münchausen syndrome and related conditions?

Introduction

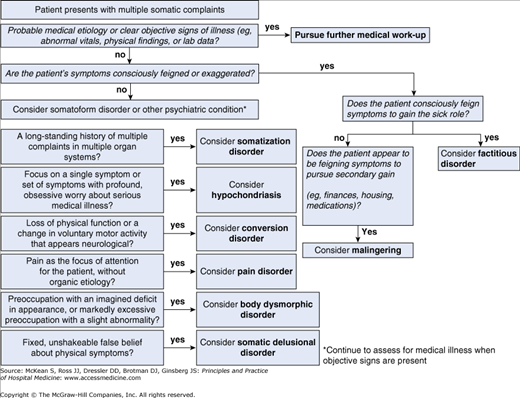

Patients who present with multiple unexplained somatic symptoms pose a significant diagnostic and management challenge for any physician. Such patients are common in medical settings, representing approximately one-third of primary care patients. The most common presenting symptoms include chest pain, fatigue, headache, and dizziness; when such symptoms go unexplained the work-up can involve unnecessary—and even dangerous—tests and procedures, as well as substantial medical cost. Figure 231-1 provides a diagnostic algorithm to assist in the evaluation of a patient who presents with multiple unexplained somatic symptoms.

General Approach to the Patient with Multiple Unexplained Somatic Symptoms

Table 231-1 outlines the major tenets of the approach to patients with multiple unexplained somatic symptoms. Before one meets with the patient, it may be helpful to consider that the individual may be difficult to interview (eg, providing a vague and/or elusive history, or being argumentative or hostile). The specific approach to a given patient with multiple symptoms depends largely on the type of physical complaints for which the patient presents. However, regardless of the chief complaint, a thorough history is critical to the evaluation of true medical and neurologic illnesses; importantly, this interview should not be conducted while one is performing the physical examination. The medical history in such a patient helps the practitioner to determine if the patient is actually experiencing the symptom reported, if the symptom has been exaggerated or feigned (eg, as in factitious illness and malingering), if there is a pathophysiological basis for the medical or neurologic complaints, if there is a characteristic pattern of symptoms, and if the patient meets criteria for a somatoform disorder.

|

Specific Disorders Associated with Unexplained Physical Symptoms

Somatization disorder involves a history of multiple unexplained physical complaints over many years that results in frequent treatment-seeking, high utilization of the health care system, significant functional impairment, and psychological distress. The symptoms include dysfunction in multiple body systems: sexual, pseudoneurological, and gastrointestinal (GI), as well as pain symptoms. Table 231-2 presents the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), criteria for somatization disorder. The disorder is much more common in women of low socioeconomic status, in minorities, in those living in rural areas, and in women with a history of sexual or physical abuse. It frequently coexists with other psychiatric illnesses, including depression, anxiety disorders, substance abuse disorders, and personality disorders; roughly three-fourths of patients with somatization disorder have a personality disorder, most commonly obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Importantly, the diagnosis of hypochondriasis and somatization disorder can be made concurrently, and up to one-third of patients with hypochondriasis meet criteria for somatization disorder.

| The patient must experience each of the four criteria at some point in their illness: |

|

| Symptoms must begin by age 29 and result in disproportionate social and/or occupational dysfunction; the symptoms are not intentionally feigned, not caused by drugs, alcohol, or medication, and not fully explained by a known physical disorder. |

Table 231-1 provides the overall approach to patients with multiple somatic symptoms. The medical history reported by patients with somatization disorder is often pan-positive, inconsistent, and disorganized; the level of patient distress is high as are their complaints of disability. Such vagueness can result from alexithymia, a difficulty identifying and describing emotions. The physical examination should be limited to the body system involved in the complaint and should focus on the objective physical findings; similarly, laboratory tests should only be obtained if there is a clear indication. Because these patients often present with menstrual and sexual complaints, the evaluation should include a thorough menstrual and sexual history; associated physical examination and laboratory testing (including pelvic examination, pregnancy test, or sexually transmitted disease testing) should be performed if indicated by the history.

Table 231-3 presents an approach to managing patients with somatoform disorders, including somatization disorder. Rather than attempting to cure the patient of somatization disorder, the physician should carefully assess the medical diagnoses, decrease the patient’s current distress, and help the patient to maintain or improve the level of psychosocial function. Additional treatment suggestions for somatization include the following:

- Consideration of referral to individual psychodynamic psychotherapy. While not a treatment for somatization disorder itself, this may help a patient who has emotional distress secondary to the physical illness or untreated symptoms secondary to sexual or physical abuse.

- Consideration of referral to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). This treatment has proven to be beneficial by helping patients to identify cognitive distortions associated with their physical symptoms.

- Avoidance of psychotropic medication. Unless there is a co-occurring psychiatric condition (eg, depression, anxiety, or substance abuse) that would benefit from medication, psychotropic medications should not be prescribed.

|