Patients with diffuse, chronic musculoskeletal pain but no evidence of arthritis or myositis account for a large number of office visits. Some of them have mild rheumatoid disease; in other cases, their symptoms are caused by bony pathology, neuropathy, or myopathy. When no source stands out, clinicians start wondering about somatization despite protests from the patient that the problem is “not in my head.”

Over the past two decades, a syndrome of diffuse, chronic musculoskeletal pain, stiffness, focal tenderness, disordered sleep, and fatigue has become increasingly recognized as an important clinical entity, designated by the term fibromyalgia. Accumulating evidence points to a possibly hereditary, central pain-processing pathophysiology, sharing features with irritable bowel syndrome, chronic idiopathic low back pain, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction

Using the research diagnostic criteria of ≥3 months of persisting widespread pain and 11 of 18 tender points on digital palpation, it is estimated that the condition affects as much as 2% to 4% of the US population, with prevalence as high as 5% among adult women, who account for 80% to 90% of cases. After osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia accounts for the most visits to rheumatologists. Recent advances in understanding the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia have led to identification of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies capable of lessening pain, improving sleep, reducing fatigue, and improving quality of life for a significant number of persons who suffer from this condition.

When encountering a patient with diffuse, chronic musculoskeletal pain, the primary care physician needs to consider fibromyalgia in the differential diagnosis, address other possible causes (see

Chapter 146), and, if present, fashion a comprehensive program of evidence-based care. While psychosocial distress can exacerbate fibromyalgia symptoms and effect response to therapy, it is no longer appropriate to view fibromyalgia as a purely psychosocial phenomenon.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY, CLINICAL PRESENTATION, AND COURSE

(1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10 and

11)

Pathogenesis

As noted, fibromyalgia is emerging as a condition of abnormal

central processing of pain rather than a somatic manifestation of anxiety, depression, or other traditional psychiatric disorder. Although the symptoms suggest somatization, careful psychological studies reveal no etiologic relationship between symptoms and psychological status. Only an increased frequency of life stress has been found. Most patients are not depressed, and any onset of depression does not correlate with the level of pain. One of the most consistent findings is augmented central pain and sensory processing leading to amplification of pain perception. Significant alterations in central nervous system neurotransmitter metabolism and function have been found manifested by abnormal levels of such key neurotransmitters as serotonin, norepinephrine, glutamate, and substance P. Disturbances of stage 4 (non-rapid eye movement) sleep are characteristic and correlate with symptoms. Functional neuroimaging reveals consistently abnormal patterns of brain activity and metabolism. These findings point to a pathophysiologic common denominator that can account for the condition’s hallmark symptoms of pain, sleep disturbance, and fatigue.

Abnormal nociception is emerging as an important element of the explanatory model (similar to its suspected role in irritable bowel syndrome—see

Chapter 74). Patients are more sensitive to pressure and show less neuronal inhibitory control in response to noxious stimuli. However, the so-called opioidergic activity is normal. There appears to be a genetic component to the condition; first-degree relatives manifest an eightfold increase in risk of developing the condition. Neuroendocrine changes have also been observed but are not sufficient to be considered etiologic. Muscle biopsy findings and electromyographic data demonstrate no consistent or unique changes. Some increased cytokine activity has been noted, but mostly involving those related to neural functioning rather than inflammation.

Although not believed to be the primary mechanism of disease, behavioral and psychosocial factors can certainly exert an effect on the clinical presentation, and the condition can exacerbate underlying psychosocial distress. Concurrent psychosocial comorbidity has been found in 30% to 60% of persons with active disease.

Clinical Presentation

The hallmarks of fibromyalgia syndrome are chronic and diffuse musculoskeletal pain, disordered sleep, and fatigue. The pain tends to be constant, aching, and concentrated in axial regions (neck, shoulders, back, pelvis). “Stiffness” is the term often used to describe the discomfort, which is characteristically worse in the morning and exacerbated by changes in the weather, cold, humidity, sleeplessness, and stress and helped by warmth, rest, and mild exercise. Points of focal tenderness may be reported in the upper and lower extremities. Patients awake from sleep feeling tired and unrefreshed. Persistent fatigue rounds out the clinical picture. The typical patient is a woman between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

Anxiety and/or depression often accompanies fibromyalgia symptoms, exacerbating them and potentially affecting the clinical course and response to treatment. At times, there is concurrent inflammatory or degenerative joint disease, which may complicate the musculoskeletal presentation.

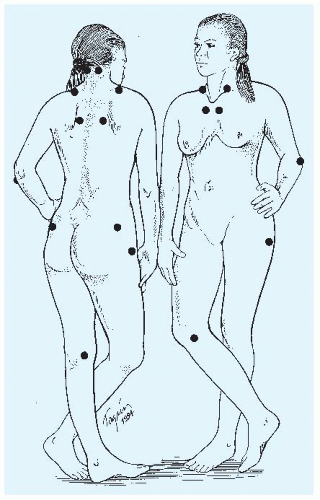

Physical examination findings are normal except for the presence of

tender points—multiple, reproducible points of exaggerated tenderness to palpation. The tender points tend to be symmetric and located in the occiput, neck, shoulder, ribs, elbows, buttocks, and knees. Eighteen characteristic locations have been identified (

Fig. 159-1).

Clinical Course

Fibromyalgia is a chronic but nonprogressive disorder that waxes and wanes, often in conjunction with changes in the weather, degree of situational stress, and amount of rest. The number and location of tender points tend to be stable over time. In some patients, the condition may become disabling, at least temporarily, but the clinical course overall is one of nonprogressive disease, with some patients experiencing spontaneous remission and many reporting some improvement with time.

The degree of disability can be considerable; up to one fourth of patients receive disability payments at some time during their illness. Unresolved psychosocial distress and lack of social support are important determinants of disability, health care utilization, a poor prognosis. Responsiveness to initial therapy portends a favorable clinical course.