Back pain is the second most frequent complaint in primary care practice and one of the leading causes of disability. Most back pain is caused by musculoligamentous strain, degenerative disk disease, or facet arthritis and responds to symptomatic treatment. Disk disease is often responsible for recurring mild discomfort of the low back and episodes of severe back pain with sciatica. Occasionally, back pain may result from problems originating outside of the spinal axis. Serious underlying problems such as tumor, infection, or vertebral compression fracture must be kept in mind.

The prevalence of back pain and the disability it causes require that the primary physician be skilled in its assessment and conservative management and knowledgeable about commonly sought complementary therapies as well as the risks and benefits of interventional measures. Even after consulting specialists, many patients will seek review of options and recommendations with their primary care physician.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

(1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9 and

10)

Musculoligamentous Strain

Muscle fibers or distal ligamentous attachments of the paraspinal muscles may tear, usually at the iliac crest or lower lumbar/upper sacral region. Resultant bleeding and spasm cause local swelling and marked tenderness at the site of injury. The patient typically presents after a specific episode of bending, twisting, or lifting. The strain is usually severe and is associated with a feeling of something giving way in the lower back. The onset of pain in the lower lumbar area is immediate. Pain radiates across the low back, often to the buttock and upper thigh posteriorly. Radiation of pain into the lower leg is rare because usually no injury to the nerve roots has occurred.

Lumbar Disk Disease

The pathophysiology of disk disease remains incompletely understood but involves degenerative changes in the disk. It is

believed that degeneration and attritional changes in the lower lumbar disks are caused by the concentration of stress at the lumbosacral level. Stresses resulting from the enormous longitudinal and shear forces that are a consequence of upright posture are aggravated by bending strain. Injury, inflammation, weakening, and tear of the disk annulus may occur and lead to localized back pain (so-called

discogenic pain). Pain receptors in the longitudinal ligaments probably mediate the recurring attacks of local back pain, which are nonradicular and most pronounced with prolonged sitting. Eventually, the disk may become so weakened that it bulges circumferentially beyond the disk interspace. Less often, a focal or asymmetric extension beyond the interspace, termed a disk

protrusion, develops. Extreme extension of the disk beyond the interspace has been called

extrusion. Historically, the term

herniation has been used to describe all these phenomena. It has been suggested that the use of the more specific terms will sharpen our understanding of the relationship between disk disease and pain syndromes. Regardless of the vocabulary, compression and irritation of a lower lumbar or upper sacral nerve root may result, and the radicular symptoms of

sciatica develop.

Sciatica is the symptomatic hallmark of nerve root irritation. Disk protrusion or extrusion is present in 95% of cases. It presents as sharp or burning pain radiating down the posterior or lateral aspect of the leg to the ankle or foot (depending on the specific nerve root involved). The pain may be worsened by cough, Valsalva maneuver, or sneezing, and it is often accompanied by paresthesias and numbness. Weakness may also develop in the areas supplied by the irritated nerve root.

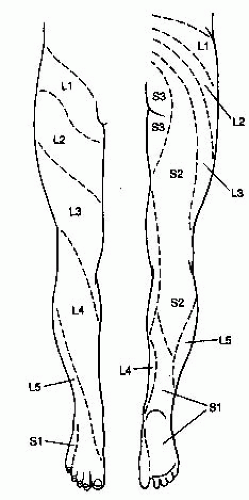

More than 95% of disk protrusions and extrusions occur at L4 to L5 or L5 to S1, with the L5 and S1 nerve roots affected, respectively. With S1 root irritation, pain, numbness, and paresthesias involve the buttock, posterior thigh, calf, lateral aspect of the ankle and foot, and lateral toes. Calf atrophy can occur, the ankle jerk can be diminished or absent, and plantar flexion weakness may be noted. With L5 root compression, pain radiates to the dorsum of the foot and great toe, and the only neurologic deficits may be extensor weakness of the great toe and numbness of the L5 area on the dorsum of the foot at the base of the great toe (

Fig. 147-1). In the rarer instance of high lumbar disk disease, pain radiates to the anterior thigh, and the knee jerk may be diminished or absent. Quadriceps atrophy and weakness may be found.

With lower lumbar disk disease, especially disk extrusion, lumbar paraspinal muscle spasm often occurs and limits lumbar motions. A list away from the side of the disk extrusion—socalled sciatic scoliosis—may develop, and often tenderness of the lower lumbar spine and sciatic notch is present. Straight-leg raising (SLR) on the affected side is limited by back and leg pain that increases on ankle dorsiflexion at the extreme of the maneuver. With upper lumbar disk disease, reverse SLR often reproduces the back and anterior thigh pain (see later discussion).

The clinical course may begin with a several-year history of recurring mild mid-low back pain related to minor back strain, with symptoms clearing spontaneously within a few days. Attacks typically increase in frequency and severity at intervals of several months to several years. Finally, an episode of persistent pain accompanied by sciatica develops, often triggered by a seemingly trivial stress (e.g., bending over in the shower to pick up the soap).

Spinal Stenosis

This often-overlooked etiology is becoming better appreciated as an important cause of chronic low back and lower extremity complaints. It occurs predominantly in elderly individuals with osteoarthritic spurring, chronic disk degeneration, and facet joint arthritis. Spinal stenosis is also found in young people who have a congenitally narrowed lumbar spinal canal. In either case, the changes narrow the canal and the neuroforamina, leading to root impingement and pain.

The characteristic symptom is pain that is worsened by standing, walking, or other activities that cause spinal extension and is relieved by rest, especially by sitting or lying down and flexing the spine and hips. Patients report pain in the low back, gluteal region, or lower extremities; often, it is bilateral. Numbness or weakness may accompany the pain in the legs. Because symptoms are often worsened by walking and relieved by sitting down and resting, they can mimic vascular insufficiency and are sometimes referred to as pseudoclaudication.

On examination, the spine demonstrates good range of motion and little focal tenderness. SLR is usually normal. Minor neurologic deficits (e.g., a diminished ankle jerk) may be present, but no pattern is characteristic.

The natural history of the condition is generally favorable, with only 15% of patients reporting clinical worsening over 5 years; 70% stay the same and 10% improve. Cauda equina syndrome is very rare in spinal stenosis.

Spondylolisthesis

The term denotes forward subluxation of a vertebral body. In adults, the condition results from degenerative changes and arthritis of the facet joints, usually at L4 to L5 or L5 to S1, with forward slippage of 10% to 20% of the diameter of the vertebral body. About 70% of patients with spondylolisthesis have chronic low back pain; sciatica is infrequent. The pain is caused by strain imposed on the ligaments and intervertebral joints.

Ankylosing Spondylitis and Other Spondyloarthropathies

The seronegative spondyloarthropathies (which include ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, and arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease) have both peripheral and axial skeleton manifestations. There is considerable overlap among these inflammatory joint diseases, which

share involvement of the sacroiliac joints and axial skeleton, limb joints, and entheses (sites of insertion of ligaments and tendons [e.g., Achilles, patellar, plantar fascia] into bone), as well as nonarticular sites (e.g., uveal tract, skin, bowel, and aortic valve). Focal tenderness may be reported at sites of involvement. A relation to mechanical stress has been invoked to explain the distribution of findings. There is a strong association with HLA-B27 positivity, suggesting an immune pathophysiology; rheumatoid factor is negative. Male predominance is the rule.

Ankylosing spondylitis is the most common of these conditions. Its characteristic features helpful for diagnosis include low back pain of at least 3 months’ duration, improvement with exercise but not with rest, limitation of lumbar spine motion and chest expansion, and bilateral sacroiliitis or severe unilateral disease. Spinal involvement is most prominent in young men; onset is gradual. Morning spinal stiffness is typical. Spinal radiographic findings are often unremarkable in the early phases, but films of the sacroiliac joints may show narrowing of the joint space and reactive sclerosis (“sacroiliitis”). Eventually, the sacroiliac joint space becomes obliterated, and fusion follows. Squaring of the vertebral bodies is the first spinal radiologic manifestation, followed by the development of syndesmophytes. Similar although less florid changes may occur in the other seronegative spondyloarthropathies.

Vertebral Compression Fracture

In normal bone, this fracture requires severe flexion-compression force. It is acutely painful. Spontaneous vertebral body collapse, or pathologic fracture, is most commonly seen in elderly persons with severe osteoporosis (see

Chapter 164), in patients taking long-term glucocorticoids (see

Chapter 105), and in cancer patients with lytic bony metastases. Usually, the history is one of sudden back pain brought on by a minor stress. The discomfort is noted at the level of fracture, with local radiation across the back and around the trunk, but rarely into the lower extremities. The fracture is more likely to occur in the middle or lower levels of the dorsal spine, which helps to differentiate the problem from lumbar disk herniations, 95% of which occur at the level of the L4 or L5 disk.

Neoplasms

The most common spinal tumor is metastatic carcinoma. Breast, lung, prostate, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary neoplasms commonly metastasize to the spine. Purely lytic lesions, which are often caused by renal or thyroid carcinoma, are seen occasionally. Myeloma is the most common primary bone tumor involving the spine. About 80% of patients are older than 50 years of age.

Typically, metastasis is hematogenous to the marrow of the vertebral bodies. Involvement of the periosteum and bony destruction lead to pain, and extension to the spinal cord can produce neurologic deficits. The disk spaces are usually spared, and disk space height is maintained, helping to differentiate the condition from degenerative disease. Collapse of the vertebral body as a result of bony destruction may be difficult to differentiate from compression fracture if osteoporosis is present. Extension into the epidural space or vertebral body collapse can lead to spinal cord compression; vascular compromise by the tumor may also contribute to cord injury.

Although only 30% of persons with metastatic disease as the cause of back pain give a history of previous cancer, in those that do, the probability of spinal metastasis is high. Approximately 90% report night pain and pain unrelieved or worsened by lying down or bed rest. A history of prior malignancy, insidious increase in pain in a region atypical for disk disease (e.g., the midback), and failure to obtain relief by lying down are highly predictive of metastatic tumor.

The clinical presentation is one of insidious onset of back pain, gradually increasing in severity and aggravated by activity and lying down. Location can be anywhere in the spine, but occurrence in an area atypical for degenerative disk disease (e.g., the midback) is suggestive. A hallmark is back pain worsened by activity and worsened, or at least not relieved, by lying down. There may be focal spinal tenderness. Extension into the epidural space is heralded by increasing back pain followed by neurologic symptoms a few weeks to months later. Besides back pain, manifestations of epidural invasion include upper motor neuron signs (proximal muscle weakness, hyperreflexia, upgoing toes), sensory loss in a dermatomal distribution, and autonomic dysfunction (urinary retention, fecal incontinence). Prognosis is poor without early intervention.

Intraspinal tumors may present in the same manner as do herniated disks. However, marked progression of neurologic deficits despite adequate conservative therapy is a clue to the existence of a tumor inside the spinal canal. Extraspinal tumors may eventually cause root impingement and simulate discogenic sciatica. Tumors of the retroperitoneum, pelvis, and large bowel may extend to the roots. This is a very late development; metastases may occur earlier.

Infection

Back pain resulting from infection is rare but important to detect. An identifiable source is found in 40% of cases; possibilities include urinary tract infection, skin abscess, indwelling catheter, and intravenous drug abuse. Vertebral osteomyelitis is usually hematogenous in origin but may occasionally result from a spinal procedure, such as lumbar puncture, myelography, diskography, or disk surgery. In addition to involving the vertebral bodies, it may extend into the disk space, producing a very painful diskitis. In the absence of diskitis, the presentation is typically one of dull, continuous back pain, often in conjunction with low-grade fever and spasm over the paraspinous muscles. Tenderness to percussion over the involved vertebrae is common, but fever and elevated white cell count are absent in up to half of cases. A compression fracture or an epidural abscess may ensue. Staphylococcus aureus accounts for about 60% of bacterial cases and enterobacteria for 30%.

Epidural abscess develops in the context of bacteremia or osteomyelitis. The infection presents as back pain, focal tenderness, and fever. Fever and spinal tenderness are present in about 85% of cases. If the condition is not promptly treated, it may extend to compromise the local blood supply to the spinal cord and rapidly progress from spinal ache to major motor and sensory deficits within hours to a few days.

Psychogenic Disease

Patients with

depression may present complaining of chronic low back pain. Often, they have a history of previous back problems or onset at the time of a minor injury, with the depression amplifying the presentation and prolonging the clinical course. Mild muscle spasm may be noted on physical examination. Characteristically, the intensity of the symptoms and the degree of disability are much greater than the minor limitations found on examination would suggest. Multiple somatic symptoms are common (see

Chapter 227). Other patients may have an underlying

somatization disorder. Many of these patients appear refractory to therapy and are often unwilling to take an active role in their treatment. Some even seem to derive a sense of legitimacy and self-worth from their suffering (see

Chapter 230).

Malingering implies conscious deception for the sake of obtaining gain from being ill. Inconsistencies among symptoms and physical findings typify the malingerer. These often can be brought out by distracting the patient.

Cauda Equina Syndrome

Although the spinal cord ends at the L1 level, the collection of nerve roots that make up the cauda equina is subject to injury by any process that compromises the spinal canal below the L1 level. Massive midline disk herniation is the most common cause of cauda compression and a serious, although very infrequent, event that requires prompt attention. In contrast to the clinical presentation of simple root impingement, the presentation in cauda equina syndrome includes urinary retention in almost 90% of cases. Another characteristic feature is saddle anesthesia (a reduction in sensation over the buttocks, upper posterior thighs, and perineum), which is reported by about 75% of patients. Both of these clinical findings are a consequence of sacral root compression, as is a decrease in anal sphincter tone, which is noted in about two thirds of cases. Sciatica and lower extremity motor and sensory deficits are prominent and often bilateral. Patients may report falling.

WORKUP

(1,

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8 and

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17 and

18)Even with the advent of sophisticated spinal imaging techniques, the history and the physical examination remain critical to the effective evaluation and management of back pain. The findings elicited are often diagnostic, and even if they are not, they can help to guide test selection and ensure timely referral. Overreliance on imaging studies often results in false-positive diagnoses.

History

In elucidating the basic features of back pain (i.e., quality, location, onset, radiation), one should also inquire specifically into symptoms that are potentially indicative of serious underlying disease (e.g., fever, progressive neurologic deficits, bilateral deficits, bladder dysfunction, saddle anesthesia, persistent pain unresponsive to bed rest or worsened by lying down). A history of recent injury and a prior history of cancer are other critical elements to be noted, as are previous therapy for back problems, recent lumbar puncture, concurrent infection, and prolonged use of high-dose corticosteroids. The presence of sciatica helps to narrow the differential diagnosis (see

Table 147-1).

Aggravating and alleviating factors may have important diagnostic significance. Morning stiffness in the back that is relieved by activity suggests ankylosing spondylitis or other inflammatory conditions. Worsening or onset of symptoms with standing or walking and relief with bending or sitting is characteristic of spinal stenosis, whereas worsening with sitting, driving, or lifting points to lumbar disk herniation. Malignancy is suggested by pain in a location atypical for degenerative disease (e.g., the midback) as well as by pain in any location that is worsened not only with activity but also on lying supine.

Associated symptoms are critical to check for, especially fever (raising the question of epidural abscess) and neurologic deficits (suggestive of cord or root injury). Is there any difficulty in standing or climbing stairs, urinating, or maintaining fecal continence? Is there truncal or saddle anesthesia? If so, a high index of suspicion is required for cord or cauda equina injury. Typical unilateral root symptoms (pain, numbness, weakness) in a characteristic lumbosacral root distribution suggest root impingement, but bilateral radicular symptoms, especially if severe and new in onset or rapidly progressive, should raise concern about cauda equina syndrome or epidural injury.

The patient should be asked to describe the effect of the back pain on daily activities. Emotional and social stressors are sought if the severity and duration of the symptoms appear to be disproportionate to the amount of organic disease present. Under such circumstances, it is important to check for depression (see

Chapter 227) and manifestations of somatization disorder (see

Chapter 230).

Laboratory Studies

For the majority of patients with low back pain, a careful history and a physical examination usually suffice for diagnosis at the time of the initial office visit. The utility of imaging studies is limited to a few specific situations, many of which are also indications for referral or consultation (see later discussion).

Lumbosacral Spine Films

In most instances, the routine ordering of plain lumbosacral spine films in patients presenting with back pain is low in yield and neither cost-effective nor useful for decision making. The finding of normal disk spaces does not rule out disk herniation, and the finding of a narrowed disk space does not distinguish between disk rupture and asymptomatic degeneration. The presence of osteophytes extending from the vertebral bodies indicates little more than long-existing disk degeneration and attempts at repair.

Nonetheless, early radiography of the back is indicated in some situations, as when the physician suspects (a) malignancy (patient >50 years of age, focal persistent bone pain unrelieved by bed rest, a history of malignancy); (b) compression fracture (prolonged corticosteroid therapy, postmenopausal woman, severe trauma, focal tenderness); (c) ankylosing spondylitis (young male patient, limited spinal motion, sacroiliac pain); (d) chronic osteomyelitis (low-grade fever, high sedimentation rate, focal tenderness); (e) major trauma; and (f) major neurologic deficits. Back pain localized to the high lumbar or thoracic region is also an indication for prompt spinal radiography because compression fracture and metastatic tumor are common in these areas.

Although plain films might be helpful in these circumstances, they are not always the imaging study of choice and should not delay proceeding to more definitive imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) (see later discussion). For example, in early osteomyelitis, there may be no visible bony changes for at least 10 to 14 days; for spinal metastasis, the false-negative rate is 30% even in persons who present with epidural cord compression and higher in earlier stages of spinal involvement. In patients with a spondyloarthropathy, characteristic changes in SI joints may not appear until years after onset of symptoms.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Clinical suspicion of cauda equina syndrome, epidural abscess, or cancer-related epidural spinal cord compression is an indication for urgent spinal imaging by either MRI or CT. Such imaging should be obtained as quickly as possible because of the risk of severe and irreversible neurologic damage in the absence of timely intervention.

CT and MRI are also indicated in persons being considered for surgical intervention to relieve persistent severe symptoms of disk herniation or other surgically amenable disease such as spinal stenosis. Both imaging modalities are very sensitive for the detection of lumbar disk disease and spinal stenosis and can provide anatomic detail of some surgical value. Although being more costly and sometimes triggering a claustrophobic response, MRI has the advantage of not involving exposure to ionizing radiation.

MRI and CT should be limited to patients who are either sufficiently symptomatic that surgical intervention must be considered or are suspected of having serious systemic disease. The high sensitivity of these tests for disk disease can produce misleading results unless the patient and clinician are aware that disk bulges and protrusions are extremely common (50% and 30%, respectively) in asymptomatic people.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

MRI is the test of choice in suspected cauda equina syndrome, epidural abscess, or cancerrelated epidural spinal cord compression by virtue of its superiority in detecting soft tissue pathology. In most instances, it obviates the need for myelography. MRI is also the best test for detecting early osteomyelitis and is the noninvasive test of choice for spinal cord tumors, epidural abscess, and epidural cord compression due to tumor or vertebral collapse. MRI may reveal such pathologic findings earlier than CT because it can detect marrow changes, which precede bony changes. MRI sensitivity for cancer-related back pain is estimated to be 93% and sensitivity to be 97%. MRI is superior to CT for the detection of disk pathology, including the tear of a disk annulus, manifesting a high-intensity zone on T2-weighted images in the posterior aspect of the involved disk; however, the relation between the finding and pain is not well established. There is no radiation exposure, but patients have to be able to lie in the scanner for up to 45 minutes. The presence of an implantable cardiac device is usually a contraindication to MRI scanning.

Rapid MRI is a variant of magnetic resonance technology that is quicker, less expensive, and slightly less sensitive than conventional MRI but is more sensitive than plain films. It has been suggested as an alternative to plain films and conventional MRI for the detection of cancer-related back pain. Decisionanalysis study finds that it is unlikely to be cost-effective: It is associated with an incremental cost per quality-adjusted lifeyear of additional survival of nearly $300,000, nearly six times the norm for a cost-effective modality.

MRI with imaging under loading stress is being explored for use in evaluation of low back pain, made increasingly possible in part by the advent of more open MRI scanners. The rationale is that images taken with the patient standing and bearing weight (i.e., under stress) may provide more clinically relevant information than those taken with the patient supine. Alternatively, in a conventional supine study, a vest can be placed on the supine patient with cords that pull toward the footplate, providing axial force. Critical review of existing studies finds the available evidence insufficient regarding efficacy with respect to clinically meaningful outcomes to warrant use of this approach outside the research setting at this time. Although such imaging is being marketed directly to consumers, they should not be encouraged to seek its use since the benefits and risks have not been adequately defined. Of note, up to 15% of patients report new or worsening pain during the procedure.

Follow-up MRI scanning in persons treated for sciatica and lumbar disk herniation was not found in randomized study to be helpful distinguishing between those who responded to treatment and those who did not. As noted, many studies have found great overlap between MRI findings in persons who are symptomatic and those who are not. Specificity is limited. Despite frequent patient requests for repeat imaging, its utility is largely limited to situations where an interventional procedure is planned on the basis of clinical findings and anatomical information is needed to help guide it, or there is new onset of important neurologic impairment or focal bone pain.

Computed Tomography.

CT scanning is much faster, less expensive, and more readily available than MRI, but it involves radiation exposure and is less sensitive for the detection of infection, tumor, nerve injury, and disk pathology. In addition, CT does not provide the visualization of the entire spine or upper vertebrae that MRI does (desirable features if the differential diagnosis includes intraspinal tumor and disk herniation at an upper level). CT does provide excellent bony detail; contrastenhanced study is a reasonable alternative to MRI when the latter is contraindicated, unavailable, or impractical. It can show changes in vertebral bodies caused by tumor and infection, although not as early as MRI, which can better detect early marrow changes.

Myelography

Traditional myelography has been largely replaced by MRI. It is usually performed in conjunction with CT on patients with progressive neurologic deficits, especially those with findings suggestive of injury to the spinal cord (e.g., loss of sphincter control, bilateral numbness, and weakness) who have a contraindication to MRI scanning. The temptation to perform myelography in the patient with chronic refractory pain is strong, but the test should be reserved for patients with objective findings that are amenable to surgery or radiation therapy. Risks include infection, bleeding, and iatrogenic worsening of the neurologic state; the frequency of adverse effects can approach 20%.

Radionuclide Scanning

The moderately high sensitivity of the technetium bone scan for osteomyelitis and metastatic disease and its wide availability make it a reasonable consideration for the patient presenting with any combination of fever, weight loss, persistent back pain, history of malignancy, concurrent infection, and markedly elevated sedimentation rate. Gallium scanning is sometimes useful in defining soft tissue involvement by infection or abscess formation.

Diskography

This invasive diagnostic procedure is performed on patients believed to be suffering from a tear of the disk annulus. Under fluoroscopic guidance, disks are injected with contrast, which characteristically increases pain in the involved disk and helps to visualize the tear on follow-up CT scan. However, even persons without a tear might have pain on disk injection. MRI can also visualize such tears but cannot confirm the relationship between the tear and the patient’s pain.

Immunoelectrophoresis

Serum and urine electrophoresis is helpful in cases of suspected multiple myeloma; crude screening with a complete blood cell count and determination of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and serum globulin level is probably sufficient if clinical suspicion is not high. A diagnosis of myeloma must be suspected if back pain in an older person is accompanied by unexplained anemia and a very high sedimentation rate. However, such findings are quite nonspecific and may also be caused by a chronic inflammatory process.