Causes and Risk Factors

The causes of alcohol abuse and dependence are incompletely understood, but the etiology is clearly multifactorial. Biogenetic, sociocultural, psychological, and behavioral influences have been identified. Understanding several typical paths to alcohol disorders improves the ability to take a relevant history and to arrive at salient therapeutic recommendations. Therapeutic plans ought to address specific vulnerabilities and comorbidities, understanding that there is considerable variability as to the natural history of alcohol dependence among and within individuals.

Biogenetic and Epigenetic Factors

Alcohol abuse clearly involves genetic determinants. Genetic factors appear to influence the metabolism of alcohol and the effects of alcohol on neurotransmitters, receptors, and cell membranes. More than 100 alcohol-responsive genes and numerous genetic risk factors have been characterized, including the genes for alcohol dehydrogenase, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), monoamine oxidase, and catechol-O-methyltransferase; more are likely to be identified. The odds ratio of developing alcohol abuse or dependence is about 10 for monozygotic twins versus about 5 for dizygotic twins. Offspring of parents with alcohol dependence frequently have an altered biologic response to alcohol, and young adult offspring with such a response are more likely to develop an alcohol diagnosis within a decade.

Evidence is accumulating that nongenetic material, such as histones, may be altered by alcohol exposure and affect transcription relevant to reward perception and drinking over the long term.

Sociocultural Factors

Poverty, socialization patterns, and cultural variables affect the probability of development of disease. Parental and peer values, attitudes, and behaviors all contribute. This helps to explain the increasing use of alcohol among women and youth and use patterns of ethnic minorities, despite an overall national decline in consumption. Price variation and local availability of alcohol (reflected by, for instance, the density of liquor stores in a neighborhood) affect the amount of drinking and, in turn, the probability of developing an alcohol diagnosis. The field of behavioral economics also helps define the types of reinforcement or punishment that might affect problematic drinking—a relevant construct in all but the most involuntary drinkers.

Psychological-Psychodynamic Factors

Underlying psychopathology and traits (e.g., dependence conflict, excessive need for power or sensation seeking, gender identification problems) contribute to predisposing a person to drink excessively, either to mask or to solve a psychological problem (the so-called self-medication). Drinking in this context is viewed primarily as a symptom of the underlying psychopathology or trait. These traits may be heritable (for instance, enhanced need to seek sensations or intolerance of negative affective states). A trauma history, by influencing levels of anxiety (even in the absence of full-blown posttraumatic stress disorder), may predispose to development of alcohol addiction.

Behavioral Factors

From the behavioral perspective, alcoholism is viewed as a learned behavior that is reversible, time limited, on a continuum with normal drinking behavior, and established by a series of learning and reinforcement experiences. The strength and pace of acquiring the habit vary with the intensity and rapidity of reinforcement. Social interactions, emotional stress, guilty or negative thoughts, and the need for sleep or pain relief precipitate and sustain drinking. Any of these precipitants coupled with learned expectations about the reinforcing, pleasurable effects of alcohol may initiate and maintain the drinking behavior.

The neurobiology of adaptation and tolerance affects the learning process. In the presence of reinforcing neurochemistry, environmental cues acquire greater salience, and learning is more likely to occur as the brain forges strong associations among behavior, environment, and reward, thus increasing the likelihood of repeating behavior that will lead to the reward. There are many candidates for the neuroanatomic substrate of such enhanced learning (e.g., dopamine in the nucleus accumbens), and they may not be specific for one reinforcing drug or another.

Epidemiologic Patterns

Alcohol use varies by age, gender, and socioeconomic group.

Young People.

Alcohol use and abuse among young people is high. Two thirds of high school seniors have used alcohol in the past year, and nearly one half report being intoxicated in that time span. Over 40% of young adults have had five or more drinks on an occasion in the last month. Adults who began smoking or drinking regularly in their early teens suffer the most serious alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems.

Women.

As a result of social change, women are consulting alcohol abuse clinics at double the former rates, and the gap between men and women in terms of alcohol consumption and problems continues to narrow.

The Elderly.

Older patients may begin to use alcohol excessively for stress, especially in reaction to the loss of a loved one, loss of physical function or role, or other stressful transitions or because of sleep difficulties. The use of alcohol along with the multiple medications that are prescribed to the elderly can be especially problematic.

Ethnic Minorities.

Certain ethnic groups are relatively protected from alcohol dependence. Some subgroups of Asians have a form of ALDH that metabolizes acetaldehyde slowly, therefore yielding higher concentrations of this chemical, which is perceived as unpleasant. People with more of this isoform of ALDH enjoy drinking less than those with proportionally less and have a lower likelihood of developing dependence.

Clinical Presentation and Course

There is a wide spectrum of drinking behaviors, from low-risk drinking to frank alcohol abuse, dependence, and deterioration.

Low-Risk Drinking

Low-risk drinking is characterized by varying consumption and beverage according to internal cues and external circumstances. The hallmarks of such moderate drinking are that it is under voluntary control and does not exceed recommended maxima. Otherwise, low-risk quantities of drinking may be considered either risky or problematic in a patient with signs or symptoms made worse by alcohol or with strong family histories. Such patients should be informed about the increased risk.

At-Risk Drinking

Persons drinking more than the recommended maxima but without negative consequences and who do not meet criteria for abuse or dependence can be classified as “at-risk drinkers.” Patients must drink more than the recommended maxima or in risky situations to fit into this category, but if there are problems stemming from drinking, then it is more useful to classify them as problem drinkers.

Problem Drinking

Such persons experience negative consequences of drinking, which might be minor and of distress only to the drinker or may cause significant problems for family, friends, or colleagues. Thus, problematic drinking may range from preclinical to severe and obvious.

Alcohol Abuse

This person meets the criteria for heavy social drinking, gets drunk on occasion, and also exhibits the negative medical, legal, social, or psychological consequences of excessive alcohol consumption. He or she makes or thinks of making attempts at cutting down or quitting. Functioning may vary from seemingly intact behavior to difficulty coping. The person may deny a drinking problem and blame external events or persons; denial is common even among those with multiple arrests for drunk driving. By definition, patients with alcohol abuse have not reached a severity sufficient for them to be diagnosed with dependence.

Alcohol Dependence

The dependent patient’s consumption of alcohol may be independent of usual precipitants or social situations, that is, the internal drive to drink is paramount and usually overwhelming. External circumstances might constrain drinking for a time, yielding a “binge pattern” syndrome. Most continue to work, even some in positions of high responsibility. Alcohol is usually given high priority (e.g., one goes to a party to drink, not to socialize). Tolerance to alcohol develops, and withdrawal symptoms (mood disturbance, tremor, nausea, sweats) may be noted during the day when the blood alcohol level drops. Drinking periodically during the day is often needed to ward off or relieve withdrawal symptoms. The patient is aware of the compulsion to drink but may have rationalized it and turn a blind eye to the experience of harm. Recognizing and overcoming such denial may require the help of family, friends, or others affected by the drinking.

Severe Deterioration

Such individuals maintain a near-constant state of intoxication, having no care for their person or surroundings, and undergo periodic hospitalizations for detoxification and for medical care necessary after alcohol-related trauma or organ damage.

Clinical Course

There is considerable individual variation. Onset ranges from an initial phase of nonproblematic drinking to immediate heavy drinking. Early onset of drinking is associated with an increased risk of alcohol abuse, but the association is not necessarily causative. The course of alcohol dependence may be punctuated by periods of spontaneous remission. The prognosis remains relatively favorable until drinking reaches the severity that is obvious clinically.

Once the addiction becomes more severe, it can be difficult to break in the absence of treatment, and the clinical course is often progressive. Twenty to fifty percent of those who meet criteria for dependence may spontaneously remit, but this lucky group may cluster at the less severe end of the dependence spectrum. The early detection of at-risk or unhealthy alcohol use is important before the patient becomes alcohol dependent. At the point of addiction, continued drinking may be punctuated by periods of abstinence or controlled drinking followed by relapse and progression, especially if there is no expert intervention. Controversy continues regarding whether total abstinence is required to prevent relapse to dependent drinking.

Medical Complications

The risk of organ damage is related in part to the dose and duration of alcohol exposure, with some conditions (e.g., alcoholic cardiomyopathy, fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, or anemia) manifesting reversibility with abstinence and others (e.g., cirrhosis or neuropathy) seeming to progress inexorably once organ damage has occurred. Predicting the risk of irreversible organ damage is imperfect; occasionally, resilience is afforded by abstinence and good nutrition. Risk appears to be a function of genetic predisposition, alcohol dose, and chronicity of exposure.

Cardiovascular Complications.

Although moderate alcohol consumption (up to two drinks a day in men, one in women) is associated with reductions in

coronary events and

coronary mortality, the consumption of more than three drinks a day

is associated with an increased risk for

hypertension and overall mortality. High levels of alcohol consumption place the patient at risk for

atrial fibrillation (see

Chapter 28) and more chronically for

alcoholic cardiomyopathy (see

Chapter 32).

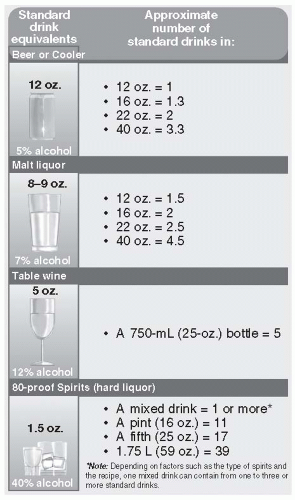

Endocrine, Gynecologic and Reproductive Complications.

Increase in the risk of osteoporosis is associated with drinking on average more than two standard drinks daily. Invasive breast cancer risk has been found to increase with as little as one half drink per day: There may be no safe level of drinking with regard to breast cancer risk. Fetal alcohol syndrome occurs in infants born to mothers who drink heavily during pregnancy. Features include permanently stunted growth, mental retardation, musculoskeletal abnormalities, poor coordination, and cardiac malformations. Incidence approaches 33% among pregnant women who drink more than 150 g (>10 standard drinks) of alcohol per day. Another one third of children born to such women have mental retardation or severe behavior disorders. Intellectual impairment in offspring is associated with as few as one to two drinks per day during pregnancy. Controversy exists about a safe or low-risk cut point, with international guidelines varying considerably.

In men, persistent impotence and loss of libido reflect impaired gonadotropin release and accelerated testosterone metabolism that occur as consequences of chronic alcohol excess; they predate end-stage liver disease.

Gastrointestinal Complications.

Alcoholic hepatitis, pancreatitis, and gastritis may follow binge drinking. Fatty liver and esophagitis ensue from chronic use. Late-stage complications include cirrhosis and oral and colorectal cancers.

Neurologic Complications.

Cerebellar degenerative disease, peripheral neuropathy, Wernicke encephalopathy, and

Korsakoff dementia are among the serious neurologic consequences of alcohol excess (see

Chapters 166,

176, and

173). Thiamine supplementation can prevent the latter two conditions and should be broadly recommended.