Approach to Minor Orthopedic Problems of the Elbow, Wrist, and Hand

Jesse B. Jupiter

David Ring

As the physician of first contact, the primary care practitioner encounters a host of elbow and distal upper extremity complaints, including pain, numbness, stiffness, a lump, or swelling. The majority represent common disorders that lend themselves to diagnosis and initial treatment by the primary care physician. Vague, diffuse complaints of pain (often activity related) can be more difficult to diagnose and treat and often remain nonspecific. Referral to an orthopedic specialist is indicated at any point the primary care provider feels uneasy.

Lateral Elbow Pain (Lateral Epicondylitis/“Tennis Elbow”)

This term denotes pain at the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) on the lateral epicondyle of the distal humerus. The term tennis elbow is misleading, in that there is no evidence that playing tennis causes this disorder. The term lateral epicondylitis is also inaccurate because pathologic specimens from operated patients have not shown any evidence of inflammation—the histologic analyses seem to reflect a degenerative rather than an inflammatory process. It is, most precisely, an enthesopathy of the origin of the ECRB. Like most enthesopathies (e.g., plantar fasciitis), it is a self-limited rite of passage through middle age.

Lateral elbow pain has often been blamed on repetitive use of the arm, but there is no evidence to support this contention. Like most musculoskeletal conditions, the cause is unknown, and the common conceptions about the illness are largely without substantiation. What is established is that the condition is age related and seen almost exclusively in middleaged patients (ages 35 to 55 years). It is self-limited and usually resolves within 12 to 18 months. Unlike other degenerative processes such as arthritis, it is not progressive. Among the myriad treatments that have been used for this disease, there is meager evidence that any of them affect the natural history of the condition, which is eventual resolution. It is not dangerous; the worst thing that can happen as a result of this disease process is complete detachment of the tendon origin from the humerus, which is uncommon and does not appreciably alter function of the elbow or wrist.

Diagnosis

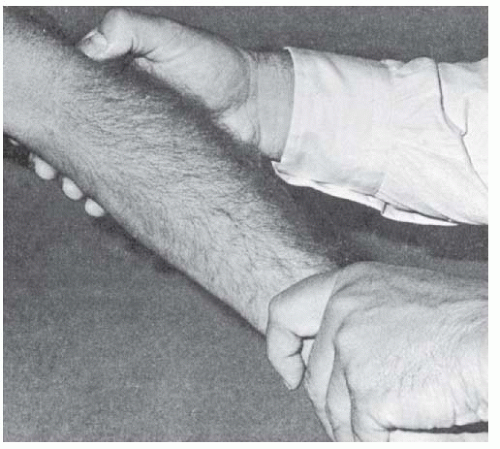

The diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis or lateral elbow pain is established by history and confirmed on examination. Patients complain of pain over the outside of the elbow that is worse with actions that use the wrist extensors (pouring milk, lifting objects with the palm facing downwards, playing tennis, etc.) and that can be isolated to a point of maximal tenderness over the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 153-1). If the pain is more diffuse, not associated with specific activities, and tenderness cannot be isolated to this point, then this diagnosis should be withheld. Some surgeons have suggested the concept of a radial nerve entrapment (radial tunnel syndrome) in this circumstance, but this is controversial, and we do not recommend the use of this diagnosis in a primary care setting. If the patient is between 35 and 65 years of age and has atraumatic lateral elbow pain, the odds are, it is lateral epicondylitis.

Examination discloses normal motion, maximal tenderness over the origin of the ECRB at the point of the lateral epicondyle, pain with passive wrist flexion and resisted wrist extension with the elbow extended, and a positive chair lift test (pain reproduced by lifting a chair or bag with some weight in it with the palm down, but not with the palm up). There is no swelling, although patients often perceive that there is. Radiographs and other imaging are not necessary when the history and exam are characteristic and there is no history of trauma—occasionally, they will show some calcification in the ECRB origin.

Management

Treatment consists primarily of palliative measures and patience while the disease runs its course. There are—to date—no proved diseased-modifying treatments. Palliative treatments include nonnarcotic pain medication (acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), ice or heat, and passive stretching and isometric strengthening of the ECRB and other wrist extensors. Forearm bands and wrist splints make some patients feel better and others feel worse. Doctors often recommend avoidance of any painful activity (e.g., racquet sports, handshake, forceful use of the arm in hammering or unscrewing jars, use of a screwdriver), but there is no evidence that this speeds the resolution of the disease, and this recommendation is disabling. Patients should be advised that all treatments are discretionary, that active use of the arm is reasonable even with pain, and that the eventual resolution without consequence is expected regardless of the treatment and activity level.

Local steroid injections are commonly used, but this is probably more because patients want something done and doctors

have nothing else to offer. Placebo injection-controlled randomized trials consistently show no benefit from steroid injection. There is a risk of skin discoloration and atrophy of the subcutaneous tissues with steroid injection. Repeat injections are not advisable.

have nothing else to offer. Placebo injection-controlled randomized trials consistently show no benefit from steroid injection. There is a risk of skin discoloration and atrophy of the subcutaneous tissues with steroid injection. Repeat injections are not advisable.

Botulinum toxin injection has been tried with mixed results in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of a single injection. In one such study, there was a significant reduction in pain that persisted up to 3 months, but without improvement in grip strength and with finger weakness in a small fraction of patients at 4 weeks that persisted up to 12 weeks in one patient. Another similarly designed trial found no benefit. Purported mechanisms of action include a direct effect on pain as well as a lessening of muscle contraction and tendinous stress. Other measures with little supporting evidence include iontophoresisdelivered corticosteroids and shock-wave therapy. Overall, randomized trials have not consistently demonstrated benefit of any treatment over the natural history of lateral elbow pain.

One potentially adverse consequence of injection treatment that provides at most temporary relief is transformation of a common, benign self-limited condition of middle age that has no proven disease-modifying treatment (and therefore of no benefit from medical care other than education and reassurance) into a disease that requires medical attention to resolve. Such “medicalization” can lead to increasingly invasive treatments ending with surgery, all of which may be unnecessary or unhelpful on the basis of current best evidence.

The abundance of these various interventions and their wide use in spite of a lack of evidence in support of their efficacy reflect the frustrating nature of this condition and the fact that patients are loathe to go without active treatment. Fortunately, the prognosis is good; symptoms eventually resolve completely.

Medial Epicondylitis (“Golfer’s Elbow”)

This condition is similar to lateral epicondylitis, but less common. It is a self-limiting middle-age enthesopathy of the flexor-pronator muscle origins from the medial epicondyle. The pain is localized to the region of the medial epicondyle and is reproduced by forcefully extending the elbow against resistance with the forearm in supination and the wrist in dorsiflexion. Treatment is similar to that for lateral epicondylitis. Steroid injection in this area risks injection into the ulnar nerve—a potentially serious problem. The possibility of an ulnar nerve entrapment (cubital tunnel syndrome) should be considered although the hallmark symptom for cubital tunnel syndrome is numbness, not pain.

Olecranon Bursitis

Patients who present with a swollen olecranon bursa have either chronic olecranon bursitis or septic olecranon bursitis. The latter will be obvious by virtue of the pain, redness, and warmth. In some cases of infection, there is an extensive cellulitis by the time the diagnosis is made, which may obscure the underlying bursitis. Almost all cases of septic olecranon represent spread from a contiguous soft tissue infection or laceration. The causative organism is nearly always Staphylococcus aureus, and empirical antibiotic treatment is usually administered—parenteral (e.g., cefazolin) for severe infections and oral (e.g., cephalexin) for milder infections. Aspiration is reserved for severe infections, infirm or immunosuppressed patients, or infections that do not respond to empirical therapy. On rare occasions, operative debridement may be required.

If the swelling of the bursa is not associated with redness or warmth, presents with only mild discomfort, and is insidious in onset, the diagnosis is chronic olecranon bursitis. Chronic olecranon bursitis has been associated with frequent pressure on this area (e.g., chess players, draftsmen) or repetitive flexion activities, but most cases are idiopathic. On occasion the bursitis is related to an inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

There is a longstanding tradition of avoiding aspiration or corticosteroid injection because of the possibility of introducing infection and the risk of a chronic fistula. These risks may be overstated; however, treatment with aspiration and injection is rarely curative, and chronic olecranon bursitis typically waxes and wanes chronically. The use of NSAIDs, ice, or compressive wrapping and the limitation of repetitive flexion and avoidance of pressure on the olecranon can help to limit swelling, but the condition is not dangerous, and none of these treatments is necessary. Surgery is considered rarely.

Nerve Entrapment Syndromes

Numbness in the hand is typically the most prominent complaint associated with cubital tunnel syndrome—ulnar nerve dysfunction where the nerve passed under the cubital tunnel fascia at the medial elbow. Entrapment neuropathy of the radial and median nerves (supinator or radial tunnel, and pronator syndromes, respectively) are proposed causes of forearm and elbow pain, but they are highly controversial because they are not objectively verifiable and are therefore a matter of faith rather than experiment. They may turn out to be illness constructions (man-made illnesses that exist only because we behave as if they exist). The primary care doctor should not diagnose radial tunnel or pronator syndromes and should regard these diagnoses with skepticism and counsel their patients to do the same.

With ulnar nerve compression, the typical complaint is of numbness in the small and ring fingers that wakes the patient at night and is present in the morning. During the day, bent elbow activities such as reading a book in bed are characteristic. Pain at the medial epicondyle is a minor complaint, and, rarely, there may be tenderness beneath the medial epicondyle. Tinel sign of the elbow (paresthesias into the small and ring fingers with tapping on the ulnar nerve at the elbow) and the elbow flexion test (elicitation of paresthesias with the elbow in a flexed position) are useful. A nighttime splint that holds the elbow in relative extension (about 40 degrees of flexion) may improve sleep, but, in practice, the splint is often more disturbing than is the numbness. If entrapment is accompanied by muscle atrophy or does not respond to simple measures, the patient should be referred for surgery. Cubital tunnel syndrome seems to present late with weakness of the first dorsal interosseous muscle established, and surgery is the only viable treatment. Unfortunately, advanced nerve damage such as constant numbness, weakness, and atrophy are usually permanent, but surgery stops the pathology and provides a small opportunity for improvement.

Septic Arthritis

Most cases of septic arthritis are the result of blood-borne infection, manifested by the rapid onset of pain, diffuse joint swelling, and erythema. Systemic symptoms are common. Septic arthritis is more common in patients with underlying conditions such as diabetes mellitus, steroid treatment, or rheumatoid arthritis. If sepsis is suspected, arthrocentesis for Gram stain and culture of the joint fluid is required (see Chapter 145). The differential diagnosis of an acute monoarthritis includes gout and pseudogout (calcium pyrophosphate deposition), both of which can be difficult to distinguish from infection before aspiration and fluid analysis have been performed. Treatment of confirmed infection includes operative debridement and intravenous administration of organism-specific antibiotics.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree