Aortic Regurgitation

Carlos A. Roldan

Aortic regurgitation (AR) is prevalent in the general population (up to 20%), similarly in males and females, but highest rates in older populations (1). AR can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

The physical examination is limited in determining the etiology and severity of chronic and acute AR.

Acute and severe AR manifests mainly by heart failure or pulmonary edema, and physical findings of AR in these patients are frequently attenuated or absent.

Aortic root dilatation is a common cause of severe isolated AR, and the physical examination is limited in determining its presence and severity.

Patients with moderate to severe AR commonly develop asymptomatic dilatation or systolic dysfunction of the left ventricle (LV). The physical examination is also limited in defining the presence and severity of LV dilatation and dysfunction.

Etiology

Common Causes

Chronic AR: Degenerative or aging valve disease, bicuspid valve with or without aortic root dilatation, healed infective endocarditis, idiopathic aortic root dilatation, systemic hypertension with aortic root dilatation, rheumatic heart disease, myxomatous degeneration with prolapse, and aortic annuloectasia.

Acute AR: Infective endocarditis, aortic dissection, and aortic trauma.

Uncommon Causes

Inflammatory diseases causing valvulitis and/or aortitis (ankylosing spondylitis, Behçet disease, Reiter syndrome, syphilitic aortitis, and giant cell aortitis), inherited noninflammatory connective tissue diseases (Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) causing valve prolapsed and/or root dilatation, and ventricular septal defects causing valve prolapse.

Echocardiography

Indications for Echocardiography

Two-dimensional (2D) and real-time three-dimensional (RT3D) transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) are indicated to define the presence, etiology, severity, follow-up, and therapy of patients with AR (2,3) (Table 8.1).

Two-dimensional and RT3D transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) are indicated to better define the etiology, mechanism, and severity of AR (2,3,4).

M-Mode, Two-dimensional, and Three-dimensional Transthoracic or Transesophageal Echocardiography

Aortic Valve and Root Morphology

Best Imaging Planes

M-mode: TTE parasternal long- and short-axis and TEE basal long- and short-axis views.

Two-dimensional and RT3D: TTE parasternal long- and short-axis and apical five- and three-chamber views; TEE basal long- and short-axis views.

Key Diagnostic Features

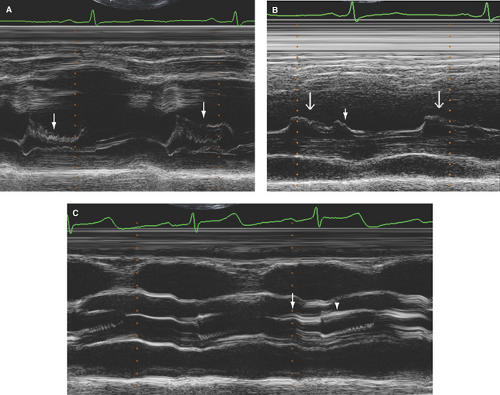

Diastolic fluttering of the anterior mitral leaflet: Best assessed by M-mode, it is specific but not sensitive, and its presence is not related to the severity of AR (Fig. 8.1A).

Table 8.1 Class I or appropriate (score 7–9) indications for echocardiography in aortic regurgitation

Symptoms of shortness of breath or heart murmur on physical exam potentially rellated to valvular heart disease (2D or RT3D)

Confirm the presence and severity of acute or chronic AR (2D or RT3D TTE).

Assessment of the etiology and mechanism of AR (2D or RT3D TTE).

Baseline study in patients with bicuspid aortic valve or other conditions associated with aortic root dilatation to assess the diameters of the aortic root and ascending aorta and degree of associated AR (2D or RT3D TTE).

Semiquantitative estimate of the severity of AR (2D or RT3D TTE).

Assessment of LV wall thickness, dimensions, volumes, and systolic function in patients with AR (2D or RT3D TTE).

Re-evaluation of patients with mild, moderate, or severe AR with new or changing symptoms or cardiac exam or to guide therapy (2D or RT3D TTE).

Re-evaluation (annual) of LV size and function in asymptomatic patients with moderate or severe AR (2D or RT3D TTE).

Re-evaluation (annual or semiannual) in patients with bicuspid aortic valves or any other condition associated with aortic disease and an aortic root or ascending aorta diameter >4 cm and any degree of AR (2D or RT3D TTE).

TEE (2D or RT3D) for evaluation of AR in patients in whom TTE provides nondiagnostic images regarding the severity or mechanism of AR and/or status of LV size and function.

TEE (2D or RT3D) intraoperatively to assess feasibility, provide guidance, and assess the results of aortic valve and/or root repair.

TTE (2D or RT3D) for evaluation of LV size and function and valve hemodynamics after valve replacement or repair to establish a baseline status.

AR, aortic regurgitation; 2D, two-dimensional; RT3D, real-time three-dimensional; LV, left ventricle; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

All of these indications are based on Level of Evidence B or C.

(Adapted from Douglas PS, Garcia MJ, Haines DE, et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/HFSA/HRS/ASNC/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate use criteria for echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1126–1166; Nishimura RA, Carabello BA, Faxon DP, et al. 2008 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation. 2008;118:e523–e661.)

Premature closure of the mitral valve (before onset of LV isovolumic contraction or onset of QRS): Best assessed by M-mode, it indicates severe AR and very high LV end-diastolic pressure and is most commonly seen in acute AR (Fig. 8.1B).

Aortic valve thickening and sclerosis: Increased thickness (>2 mm) and reflectance of any cusp is best assessed by M-mode (7) (Fig. 8.1C). In the author’s laboratory, mild sclerosis is defined as any cusp with sclerosis with normal mobility; moderate sclerosis if decreased cusp mobility is present; and severe sclerosis if associated with decreased mobility and increased, but <2.5 m/second, valve peak velocity.

Aortic valve mobility: Subjectively assessed by TTE and TEE. Normally, aortic cusps move closely (within 3 mm) and parallel to the aortic root walls (Fig. 8.1C). However, no specific parameters have been defined for assessing the severity of decreased cusp mobility.

Degenerative aortic valve disease: Sclerosis of one or more cusps predominantly at the commissural margins and basal portions with decreased mobility. Sclerosis can be localized, nodular, or diffuse, but a mixed pattern is most common (8) (see Fig. 9.1).

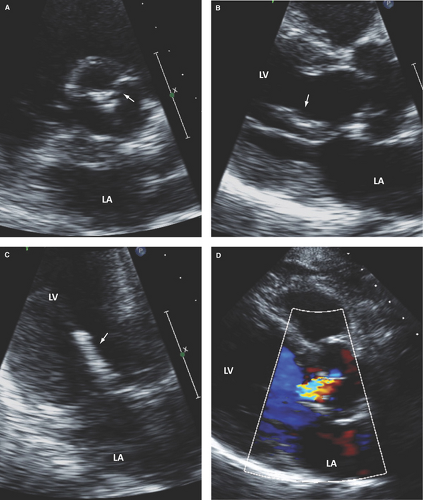

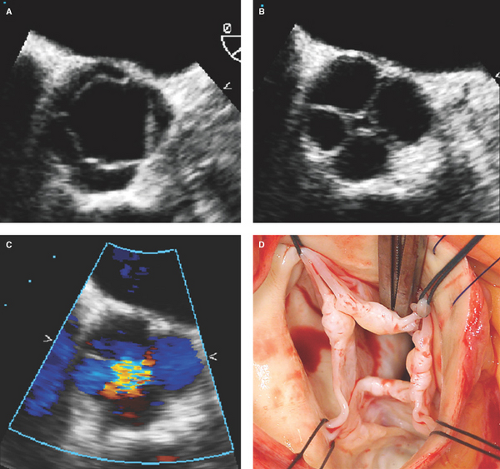

Bicuspid aortic valve: Has two cusps of unequal size, single linear commissure, sclerosed raphe with partial or complete cusp fusion (most commonly of the right and left coronary cusps), systolic doming of pliable cusps, and eccentric closure in relation to root walls (Figs. 8.1C and 8.2). Two-dimensional and especially RT3D TEE define better than 2D TTE the morphology of normally functioning, regurgitant, or stenotic bicuspid aortic valves (4,9,10) (Fig. 8.3). Associated aortopathy with variable degrees of root dilatation is common (Fig. 8.3B). Regurgitant quadricuspid aortic valves are also better detected and characterized by TEE (Fig. 8.4).

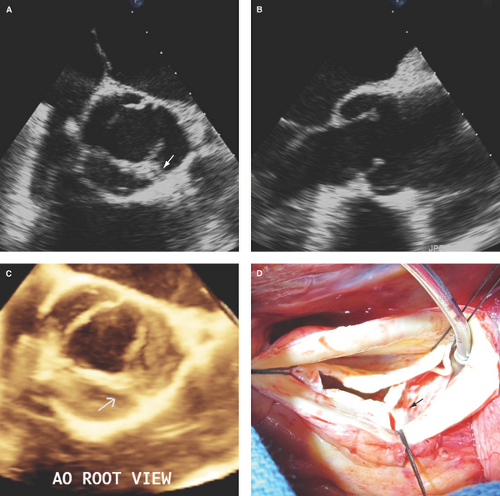

Rheumatic and nonrheumatic inflammatory valve disease: In rheumatic disease, there is commissural fusion (best seen from short-axis view), thickening of the tip portions, and retraction of the cusps. Often, all commissures are affected. With the exception of commissural fusion, other nonrheumatic valvulitis causes similar echocardiography (echo) abnormalities (Fig. 8.5).

Infective endocarditis: Characterized by leaflet vegetations and associated complications of leaflet perforation, annulus or root abscesses, and leaflet or root aneurysm or pseudoaneurysms. Although 2D TTE can detect valve vegetations, 2D and especially RT3D TEE are superior to 2D TTE in the detection and characterization of valve vegetations and associated complications (5,11,12) (Fig. 8.6).

Myxomatous aortic valve disease with prolapse: This condition is an uncommon but important cause of AR (Fig. 8.7).

Aortic root dilatation: Categorized as mild if the tubular portion measures 3.7 to 4.5 cm, moderate if it measures 4.6 to 5.0 cm, and severe if it measures >5 cm (Fig. 8.3B).

Aortic root sclerosis: Anterior or posterior root wall increased reflectance and thickness >2.2 mm (13). The author defines it as mild when a sclerotic wall measures 2.3 to 3.0 mm, moderate if it measures 3.1 to 4.0 mm, and severe if it measures >4 mm.

Aortic valve regurgitant orifice area: Central gap bordered by the cusps’ edges during early diastole using 2D or RT3D TEE basal short-axis view (14). An orifice area <0.2 cm2, >0.2 to ≤0.4 cm2, and >0.4 cm2 indicate mild, moderate, and severe AR, respectively (Figs. 8.4B and 8.5D).

AR jet lesions of the anterior mitral leaflet and/or chordae tendineae: Focal nodular or less commonly diffuse sclerosis of the mid to distal anterior mitral leaflet and/or chordae tendineae. These lesions are commonly seen with at least mild AR, but their presence and severity are not related to the severity of AR (Fig. 8.2B–C).

Hemodynamic Impact of Aortic Regurgitation on the Left Ventricle and Left Atrium

Best Imaging Planes

M-mode and 2D TTE parasternal long- and short-axis views.

Figure 8.3: Bicuspid aortic valve by 2D and RT3D TEE. A. Two-dimensional basal short-axis view of a bicuspid aortic valve with partial fusion of the right and left coronary cusps by a raphe (arrow) with associated cusp thickening and decreased mobility. B. Two-dimensional long-axis view showing asymmetric length of the aortic cusps, cusp thickening predominantly at the tip portions and decreased doming mobility of the cusps, and associated moderate (4.8 cm diameter) dilatation of the aortic root. C. RT3D TEE aortic root view defining better the partial fusion with a short raphe (arrow) and thickening with decreased mobility of the bicuspid valve cups. Associated severe AR was demonstrated by color Doppler (see Fig. 8.13A–C). D. Surgeon’s view of the bicuspid aortic valve with a short raphe (arrow) and tip thickening of the cusps. AO, aortic.

Two-dimensional and RT3D TTE apical views.

M-mode and 2D TEE transgastric short- and long-axis views.

Two-dimensional and RT3D TEE basal four- and two-chamber views.

Diagnostic Methods

By M-mode, LV end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters with respective indexes and LV shortening fraction provide key information regarding the severity and

prognosis of AR and indicate whether valve replacement or repair is needed.

By 2D and RT3D TTE and TEE, LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes, total stroke volume, and ejection fraction (EF) can be accurately quantified (Fig. 8.8).

LV radius to wall thickness ratio and end-systolic wall stress also assess the severity of AR.

Key Diagnostic Features

Size and volumes of the LV and left atrium (LA) are generally normal in mild to moderate AR but are commonly increased in moderate to severe or severe AR.

Pitfalls

Characterization of the aortic valve is limited by M-mode and frequently by 2D and RT3D TTE.

Diastolic fluttering of the mitral valve is specific but not sensitive for detection of AR.

LV diameters and fractional shortening are less reproducible by 2D echo than by M-mode, and both are probably less reproducible than RT3D.

LV and LA dimensions and volumes generally do not separate mild from moderate AR.

Other concomitant valvular or myocardial diseases can affect LV and LA dimensions.

Figure 8.5: Aortic valvulitis by TEE. A. Two-dimensional long-axis view during systole showing cusp thickening, retraction, and decreased doming mobility predominantly of the right coronary cusp. B. Two-dimensional long-axis view during diastole showing thickening predominantly of the tip portions and retraction of the cusps leading to an incomplete coaptation (arrow). C, D. RT3D TEE aortic root views of the aortic valve during systole (C), defining better the moderate and diffuse thickening of the cusp tips and decreased mobility of all three cusps. Also note a well-defined oval nodularity at the tip and ventricular side of the right coronary cusp (arrow). D. During diastole, note the cusps retraction leading to an incomplete central coaptation (arrow). Moderate AR was demonstrated by color Doppler (see Fig. 8.14). |

Doppler Echocardiography for Assessment of the Severity of Aortic Regurgitation

Pulsed Wave Doppler

Best Imaging Planes

TTE apical three- and five-chamber views and supra-sternal notch view for assessment of aortic flow.

TTE parasternal long-axis or TEE basal long-axis views for assessment of left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) diameter.

Diagnostic Methods and Formulas

Total stroke volume = LVOT area (D2/4 or π × r2) × VTILVOT where D indicates LVOT diameter; r, LVOT radius; and VTI, velocity time integral.

Forward stroke volume = RVOT area (D2/4 or π × r2) × VTIGVOT where D indicates right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) diameter and VTI obtained from the parasternal short-axis view at the pulmonic valve level. Mitral annulus diameter and mitral inflow VTI can be used if less than moderate MR is present.

Regurgitant volume = total stroke volume – forward stroke volume

Regurgitant fraction = regurgitant volume ÷ total stroke volume

Regurgitant orifice area = regurgitant volume ÷ VTI of AR jet by continuous wave Doppler

Flow velocity reversal in the aortic arch or descending aorta: Short-lasting diastolic flow reversal is normal in

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree