Aortic Dissection

Jay Shah

Alan C. Braverman

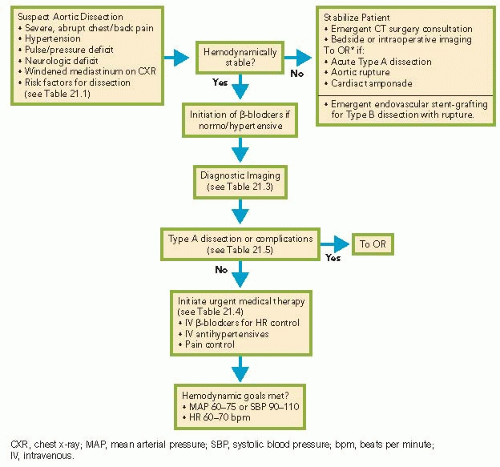

Aortic dissection is a life-threatening acute aortic syndrome that accounts for a small but significant proportion of cardiovascular system disease, with an incidence of approximately 5 to 30 per million people per year. It carries substantial morbidity and mortality, with a mortality rate up to 1% per hour within the first 24 to 48 hours. An algorithm for the immediate approach to the patient with aortic dissection is presented in Algorithm 21.1.

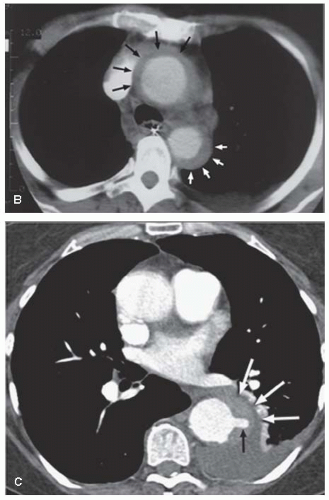

Classic aortic dissection results from a tear in the intimal layer of the aorta, allowing blood to enter the medial layer and propagate in an anterograde or retrograde direction, resulting in a second, “false” lumen. Additional intimal tears may occur, and allow reconnection with the true lumen. Variants of aortic dissection include aortic intramural hematoma (IMH) and penetrating atherosclerotic aortic ulcer (PAU), which together account for 10% to 20% of acute aortic syndromes (Figure 21.1). In aortic IMH, rupture of the vasa vasorum leads to hemorrhage in the medial layer without an intimal tear or communication with the aortic lumen. IMH of the aorta is generally treated in a similar fashion as aortic dissection, with emergency surgery for ascending aortic IMH and medical therapy for descending aortic IMH. PAU can arise when atherosclerotic lesions of the aorta develop ulcerations that penetrate the intimal and medial layers, and may form a false aneurysm that may lead to aortic dissection or rupture. Between these two variants of acute aortic syndromes, IMH is more likely to progress to classic aortic dissection and PAU is more common in the descending aorta. Once aortic dissection occurs, shear forces stemming from the rate of change in pressure (dP/dt) and mean blood pressure contribute to spread of the tear.

Several conditions predispose the aorta to dissection, most as a result of abnormalities in the arterial wall composition (Table 21.1). Approximately 75% of patients with aortic dissection have hypertension. Patients with bicuspid aortic valves or conditions, such as the Marfan syndrome, Loeys—Dietz syndrome, vascular Ehlers—Danlos syndrome, or familial thoracic aortic aneurysm/dissection, are particularly prone to aortic dilation and dissection. Cocaine or methamphetamine-induced hypertension, inflammatory conditions such as giant cell arteritis, or direct trauma from catheterization or aortic surgery can disrupt the aortic intima. Once the intima becomes injured, it is vulnerable to shear stresses and may progress to rupture or dissection.

There are several classification systems for aortic dissections, and involvement of the ascending aorta is the defining characteristic (see Figure 21.2). DeBakey types I and II and Stanford type A dissections involve the ascending aorta. DeBakey type III or Stanford type B dissections do not involve the ascending aorta. Classification of the anatomy is important because the decision regarding surgical or medical management

is dependent on the location of the dissection. Broadly, dissections of the ascending aorta (types I, II, and A) require immediate surgical repair, while those involving the descending aorta (type III or B) are initially treated medically.

is dependent on the location of the dissection. Broadly, dissections of the ascending aorta (types I, II, and A) require immediate surgical repair, while those involving the descending aorta (type III or B) are initially treated medically.

The clinical presentation of aortic dissection may be quite variable, and one must maintain a high index of suspicion for the diagnosis. In contrast to the crescendo discomfort of angina pectoris, the pain of acute dissection is maximal at its onset, usually sudden and severe, and often described as a sharp, tearing pain in the chest, neck, or interscapular areas. In addition to the dissection itself, presenting symptoms

may also be related to malperfusion or complications involving various organ systems. Physical examination should include a complete pulse exam and blood pressure in both arms and legs, as there may be pulse or pressure deficits. Cardiac auscultation may reveal an aortic regurgitation murmur. However, pulse differentials and an aortic regurgitation murmur are present in a minority of patients, and physical examination alone is not sufficient to rule out aortic dissection.

may also be related to malperfusion or complications involving various organ systems. Physical examination should include a complete pulse exam and blood pressure in both arms and legs, as there may be pulse or pressure deficits. Cardiac auscultation may reveal an aortic regurgitation murmur. However, pulse differentials and an aortic regurgitation murmur are present in a minority of patients, and physical examination alone is not sufficient to rule out aortic dissection.

TABLE 21.1 Risk Factors for Aortic Dissection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree