Key Clinical Questions

What are the most important pharmacologic characteristics of specific parenteral and oral anticoagulants that are licensed for use in Europe and North America?

What determines the choice of anticoagulant in the prevention and treatment thromboembolism?

What determines the choice of anticoagulant in the management of patients with acute coronary syndromes?

Introduction

Unfractionated heparin and coumarins were discovered more than 60 years ago and for more than 40 years they were the only anticoagulants available to hospitalists. Now in 2011, several new anticoagulants have been licensed for clinical use and many more are under development. The increase in the number of licensed anticoagulants has expanded the choices available for physicians and patients but has also created new challenges in selecting the optimal therapeutic strategy. Anticoagulant drugs differ in their route of administration, speed of onset and offset of anticoagulant effect, half-life, reversibility, route of excretion, and availability of an antidote, and hospitalists need to be familiar with the properties of individual anticoagulant drugs in order to select the best agent for a particular clinical situation.

The first part of this chapter briefly reviews the most important pharmacologic characteristics of parenteral and oral anticoagulants that are licensed for use in Europe and North America. The second part of this chapter considers the choice of anticoagulant in the prevention and treatment of thromboembolism and management of patients with acute coronary syndromes and illustrates these choices using selected patient scenarios.

Established and New Anticoagulant Drugs

Rapidly acting parenteral drugs, such as heparin, have been used for the prevention and initial treatment of thromboembolism during revascularization procedures, whereas the slower-acting oral vitamin antagonists (eg, warfarin) have been used for long-term use. Low molecular weight heparin, fondaparinux and bivalirudin have replaced heparin for many indications, and new oral anticoagulants, including the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate, and the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban have begun to replace vitamin K antagonists for long-term use. Dabigatran has been licensed for treatment of atrial fibrillation in Europe and North America and both dabigatran and rivaroxaban have been approved in North America and Europe for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Apixaban has been approved in Europe for the prevention of venous thromboembolism but is not yet approved for this indication in North America.

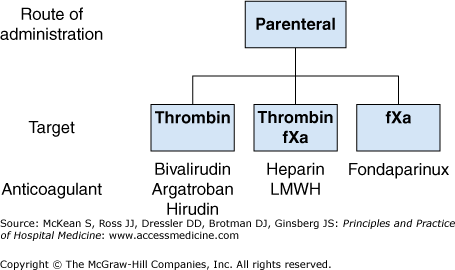

Figure 261-1 lists the parenteral anticoagulants, subdivided according to their pharmacologic target, that are licensed for use in Europe and North America. The pharmacologic properties of these agents are summarized in Table 261-1.

| Characteristic | Unfractionated Heparin | LMWH | Fondaparinux | Bivalirudin | Hirudin | Argatroban |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Xa and thrombin | Xa and thrombin | Xa | Thrombin | Thrombin | Thrombin |

| Dosing | SC, IV | SC, IV | SC, IV | IV | IV | IV |

| Half-life | 40 minutes | 3 to 6 hours | 17 hours | 25 minutes | 1–2 hours | 40 minutes |

| Renal clearance | Minimal | 100% | 100% | 20% | 90% | None |

| Routine coagulation monitoring | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Antidote | Yes, protamine | Partial, protamine | No | No | No | No |

Heparin has important limitations because it has an unpredictable anticoagulant effect. Thus it requires routine coagulation monitoring, and it causes heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, which can result in life-threatening thrombotic complications, including limb ischemia, stroke, or death. Nonetheless, heparin retains several important advantages over more recently introduced parenteral anticoagulants such as low-molecular-weight heparin and fondaparinux. Heparin is not cleared by the kidneys, which means that it can be used in patients with renal insufficiency, and the anticoagulant effect of heparin can be neutralized by protamine, a basic protein that binds to heparin to form a stable salt that is cleared from the circulation. Thus, heparin remains widely used in critically ill patients and in those undergoing invasive procedures.

Low-molecular-weight heparins (dalteparin, enoxaparin, nadroparin, reviparin, tinzaparin) are chemically or enzymatically derived from longer heparin chains. Because of their shorter chain length, low-molecular-weight heparins are much less likely than heparin to bind nonspecifically to cells and proteins and have a longer half-life (three to six hours) and a more predictable anticoagulant effect. Low-molecular-weight heparins can be given subcutaneously in fixed doses without routine coagulation monitoring and are less likely than heparin to cause immune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia or osteoporosis. The anticoagulant effect of low-molecular-weight heparins can be partially reversed with protamine.

Fondaparinux is a synthetic pentasaccharide that selectively inhibits factor Xa. Fondaparinux does not bind nonspecifically to cells or proteins, has a half-life of 17 hours, and has a predictable anticoagulant effect. Fondaparinux can be given in fixed doses by subcutaneous injection once daily, does not require routine coagulation monitoring, and it is renally excreted. Fondaparinux has been associated with the formation of anti-heparin/platelet antibodies, but there is no evidence that it causes heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Fondaparinux does not have an antidote.

Bivalirudin is an intravenous direct thrombin inhibitor that blocks the interaction between thrombin and its substrates. Bivalirudin has a half-life of 25 minutes after intravenous injection, making the lack of an antidote less problematic than for longer-acting anticoagulants. It is about 20% renally cleared and the half-life of bivalirudin is prolonged in patients with renal impairment. Bivalirudin does not cause heparin-induced thrombocytopenia or osteoporosis.

The direct thrombin inhibitors, hirudin and argatroban, are less widely used than bivalirudin. Hirudin has a half-life of one to two hours and is 90% renally cleared. Argatroban has a half-life of about 40 minutes and unlike both bivalirudin and hirudin it is nonrenally cleared, making it suitable for use in patients with severe renal insufficiency.

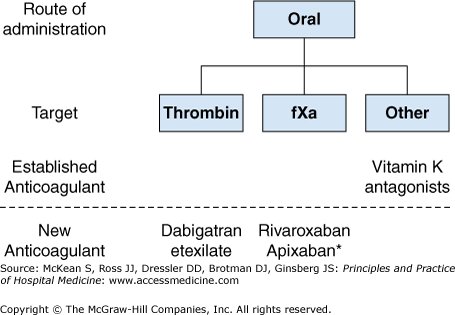

Figure 261-2 lists the oral anticoagulants, subdivided according to their pharmacologic target, that are licensed for use in Europe and North America. The pharmacologic characteristics of the oral anticoagulants are summarized in Table 261-2.

| Characteristic | Warfarin | Dabigatran Etexilate | Rivaroxaban | Apixaban |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Vitamin K epoxide reductase | Thrombin | Factor Xa | Factor Xa |

| Dosing | Variable, once daily | Fixed, once or twice daily | Fixed, once or twice daily | Fixed, twice daily |

| Half-life | 40 hours | 12 to 14 hours | 7 to 11 hours | 12 hours |

| Renal clearance | None | 80% | 66%* | 25% |

| Routine coagulation monitoring | Yes | No | No | Not required |

| Antidote | Yes, vitamin K | No | No | No |

| Drug interactions | Multiple | Potent inhibitors of P-gp† | Potent inhibitors of CYP3A4 and P-gp† | Potent inhibitors of CYP-3A4§ |

For more than 50 years, vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin, were the only orally active anticoagulants that were licensed for long-term clinical use. Warfarin is an effective anticoagulant but has numerous limitations, including a slow onset and offset of action, variable dose requirements reflecting the effect of food and drug interactions and genetic polymorphisms that influence drug metabolism, and a narrow therapeutic window. As a result, routine coagulation monitoring is necessary to achieve a therapeutic anticoagulant level. Two important advantages of the vitamin K antagonist over newer oral anticoagulants are that warfarin’s anticoagulant effect can be readily reversed with the administration of vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, or prothrombin complex concentrates, and that warfarin is nonrenally cleared, making it suitable for use in patients with severe renal impairment.

Dabigatran etexilate is a prodrug of dabigatran, a specific, competitive, and reversible direct inhibitor of thrombin. Dabigatran etexilate is given orally, has a bioavailability of about 6%, and is rapidly converted to its active form after absorption via the gastrointestinal tract by esterases. Dabigatran has a half-life of 12 to 14 hours in patients with normal renal function, it is 80% renally cleared, and it does not have an antidote. Dabigatran etexilate is a substrate of the P-glycoprotein transporter in the gut that is involved in the transport of drug from the cell into the lumen of the gut. The coadministration of drugs that inhibit the P-glycoprotein transporter, such as amiodarone, significantly increases drug levels of dabigatran in the blood. Dabigatran is given once or twice daily.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree