ANORECTAL ABSCESS

CASE SCENARIO

A 45-year-old man with a past medical history of hypertension presents to the emergency room with a 2-day history of rectal fullness and perirectal pain. The pain is throbbing in nature and mildly worsens with a bowel movement.

The patient is afebrile, with blood pressure elevated to 150/95. On examination, his abdomen is non-tender. Rectal examination reveals an exquisitely painful mass in the left lateral position. A full rectal examination is impossible due to the pain. His lab work is unremarkable with the exception of a leukocytosis to 15.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although failure of patients to seek medical attention and misattribution of anorectal pain to hemorrhoids confound epidemiological data, an estimated 100,000 cases of anorectal abscess are diagnosed yearly in the United States.1 Most patients present between the ages of 20 to 60, with a mean age of 40 in both genders.2 In adult patients, males are twice as likely to develop an abscess compared to women. Interestingly, neither personal hygiene nor sedentary occupation has been linked to development of an anorectal abscess.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

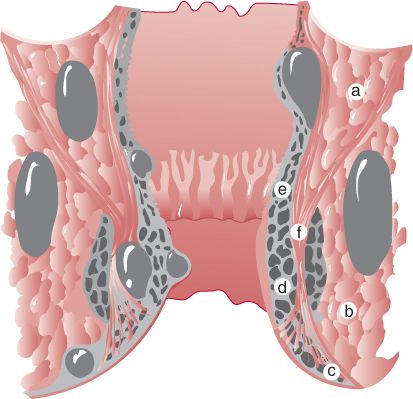

Anorectal abscesses originate from an infection of the anal crypt gland. When the gland becomes obstructed, suppuration follows the path of least resistance into the wall of the anal canal. Knowledge of anatomy is essential in knowing the five possible tracts (Figure 25–1):

Figure 25–1 Diagram of acute anorectal abscesses and spaces. (a) Supralevator space, (b) ischiorectal space, (c) perianal space, (d) marginal (mucocutaneous) space, (e) submucosal space, (f) intersphincteric space, (g) ischiorectal space. (Reproduced with permission from Doherty GM. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010.)

1. Intersphincteric abscess—the infection extends between the internal and external sphincter, sparing the anal verge.

2. Perianal abscess—the infection extends between the internal and external sphincter to reach the anal verge.

3. Ischiorectal abscess—the infection ruptures through the external sphincter into the ischiorectal fat.

4. Supralevator abscess—the infection extends above the levators.

5. Horseshoe abscess—the infection starts in the deep postanal space and then extends to either or both ischiorectal fossae.

In terms of natural history of the disease, there are the three possible outcomes. An abscess can

1. drain and heal

2. drain and form a fistula

3. remain undrained and progress to anal sepsis, with high morbidity and mortality

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The primary presenting symptom of an anorectal abscess is pain in the anal or rectal area. The pain is constant and is not necessarily associated with bowel movements. Systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise are common. With spontaneous opening, purulent rectal drainage may be seen.

On physical examination, low abscesses (perirectal and ischiorectal) are identified by swelling, cellulitis, and exquisite tenderness to palpation. Higher abscesses (horseshoe, supralevator) will likely be associated with pain, fever, and urinary retention. An intersphincteric abscess can be difficult to diagnose, as it is associated with exquisite tenderness on palpation, but no other obvious examination findings.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

As the most common presenting symptom of an anorectal abscess is pain, a number of other conditions should be considered. These include a thrombosed hemorrhoid, anal fissure, levator spasm, sexually transmitted disease, proctitis, and neoplasm (Table 25–1). However, only an anorectal abscess is a surgical emergency and should be ruled out first. The clinician should never attribute acute anal pain to thrombosed internal hemorrhoids (these never cause pain unless incarcerated and visible) or perianal cellulitis (this is almost always associated with an underlying abscess), as these entities are extremely rare, and misdiagnosis may allow occult anal sepsis to progress untreated.

WORKUP AND CHOICE OF IMAGING

In a patient with a history and physical examination consistent with a perirectal abscess, it is most prudent to proceed to incision and drainage. However, if the presence of a drainable collection is uncertain, there are a number of imaging modalities to clarify the diagnosis.

Computed Tomography (CT)

Computed Tomography (CT)

A CT scan of the pelvis with intravenous contrast allows identification of the abscess, and can help exclude a supralevator component. Although some authors claim differentiation on CT between perirectal cellulitis and abscesses, the distinction is not clinically relevant.3 Drainage should be undertaken in any patient with anal cellulitis and phlegmon on CT, as these findings frequently translate into true purulence at the time of an intervention. In fact, one study reports overall sensitivity of CT in identifying abscess to be only 77%.4 Limitations of CT include unreliable identification of the levator ani and exposure to ionizing radiation.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is useful in patients with complex fistulizing disease, and has proven especially helpful in confirmation of a fistulous tract in patients with prolonged drainage from a prior debridement site. Sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 69% have been reported for detection of fistula-in-ano.5 However, MRI is not the test of choice in a patient who presents with a de-novo abscess, due to both time and to cost.

Ultrasound (US)

Ultrasound (US)

Two forms of US are available for anorectal examination. Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) involves placement of a circumferential 2D or 3D probe into the anal canal. It allows for a well-defined circumferential view of the anal sphincter complex and is sensitive in the detection of small fluid collections, both in the intersphincteric space as well as above the anal verge. However, the probe is not likely to image a supralevator abscess or an ischiorectal abscess well. Another ultrasound technique involves endoscopic placement of a 2D ultrasound probe at an area of interest—Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS). This technique requires knowledge of the suspected abscess area and is therefore less useful in situations when the patient does not have obvious swelling or localizing symptoms on examination. Furthermore, both modalities are painful and may be poorly tolerated. As such, their use in the treatment of perirectal abscess has been limited.

IMAGING FINDINGS

CT Scan

CT Scan

The two main objectives in reading a CT scan are to determine whether or not there is an abscess, and then to identify the location of the abscess relative to the sphincter and the levator muscle. Findings on CT include a rounded, ring-enhancing focus of mixed attenuation in the perirectal area. Gas may be present in the abscess. Increased attenuation in the adjacent fat pad representing inflammatory changes can also be seen.

In determining the location of the abscess, knowledge of pelvic anatomy is important. The pelvis is divided into two relevant anatomical compartments: supralevator and infralevator. The supralevator space is divided into medial and lateral components by the perirectal fascia. The medial space is the perirectal space, and the lateral space is the pararectal space. The posterior infralevator space contains two compartments: the deep postanal space and the superficial postoanal space. Both of these spaces communicate with the ischioanal space, and it is this connection that leads to the formation of horseshoe abscesses (Table 25–2 and Figures 25–2 through 25–5).