FIGURE 13.1 Original from Stubblefield and O’Dell’s “Principles and Practice of Cancer Rehabilitation,” Demos Medical Publishing.

C. Treatment of spinal cord tumors. The treatment for almost every spinal cord tumor involves surgical resection; the type of tumor determines whether adjunctive therapy with chemotherapeutic agents or radiation is indicated. If the patient has received chemotherapeutic agent, the anesthesiologists should familiarize themselves with the potential side effects. For example, cisplatin is associated with nephrotoxicity and electrolyte disturbance, and sirolimus is associated with thrombocytopenia. In all cases, complete resection is rarely a guarantee of cure. In many of the primary tumors, 5-year survival is >70%, but recurrence is likely.

CLINICAL PEARL

If the patient has received chemotherapeutic agent, the anesthesiologists should familiarize themselves with the potential side effects.

1. Chordomas. Chordomas are rare tumors which are locally invasive and frequently recur. Wide local excision is attempted, although complete resection is often not possible [2]. Postoperative radiation therapy is frequently employed [3]. Chemotherapeutic agents with activities include the following: Imatinib plus or minus cisplatin, sirolimus, sunitinib, and erlotinib [4]. Sarcomas and lymphomas may be primary or secondary disease in the spine. These tumors are generally treated with a multimodal approach, which includes surgical resection, radiation, and chemotherapy.

2. Benign primary bone lesions. These may occur in the spine and are treated with resection alone. These include osteoid osteomas, osteoblastomas, osteochondromas, chondroblastomas, giant cell tumors, vertebral hemangiomas, and aneurysmal bone cysts.

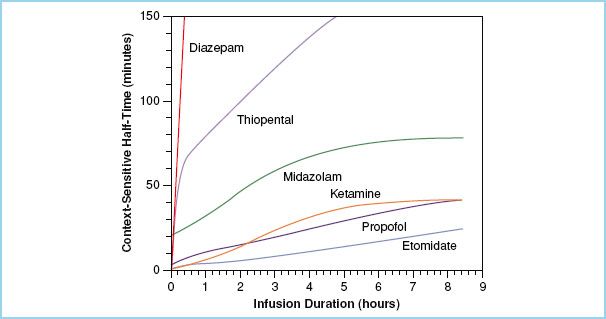

FIGURE 13.2 Plot of the context sensitive half-time versus duration of infusions of several anesthesia medications. (Redrawn from Hughes MA, et. al. Context-sensitive half-time in multicompartment: Pharmacokinetic models for intravenous anesthetic drugs. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:334–341, with permission).

3. Intramedullary tumors. Intramedullary gliomas are preferentially treated surgically [5]. The initial step is an attempt at curative resection. There have not been randomized trials of radiation therapy. The roles of radiotherapy and chemotherapy have been as adjuvants to surgery in the case of noncurative resections or recurrence. The most recent guidelines suggest that patients who have had curative resections should not receive radiation.

4. Intradural-extramedullary tumors. These tumors include meningiomas, schwannomas, and ependymomas and are preferentially treated with surgery. Radiation has been used for recurrence which is not amenable to resection; chemotherapy is not indicated [6,7].

5. Treatment options for spinal cord tumors resulting from metastases. Several cancers are likely to result in metastases to the spine; 90% of patients dying of prostate cancer and 75% of patients dying of breast cancer have metastases to the spine [8]. Metastatic cancer of the spine may require surgical treatment when it results in a pathologic fracture causing pain and instability or epidural spinal cord compression (ESCC) resulting in a neurologic deficit or cauda equina syndrome. Vertebral metastases are significantly more common than ESCC. The three most common tumors are prostate cancer, breast cancer, and lung cancer. Use of radiation or chemotherapy is dependent on the type of tumor.

Because of their potential for invasion of local tissues and generous blood supply, the resection of metastatic lesions of the spine can have significant potential for intraoperative blood loss (especially metastatic renal cell carcinoma).

III. Preoperative assessment. All the standard issues associated with the preparation of any patient for anesthesia apply to patients with spinal tumors, including an underlying understanding of their physical status, their medication regimens, any potential allergies, and their surgical history. In addition, preparation for anesthetic care of patients with spinal tumors starts with an understanding of the chief complaint that brought the patient to surgery.

2

A. Pain. Pain is the most common symptom present among patients with spinal cord tumors and may be associated with varying levels of neurologic deficit. Use and schedule of pain medications should be noted, including current medications and medications used previously. This history will help the anesthesia team instruct the patients how to manage their medication regimen prior to surgery, will influence the intraoperative approach, particularly for opioid usage, and will assist in managing acute postoperative pain.

CLINICAL PEARL

Pain is the most common symptom present among patients with spinal cord tumors and may be associated with varying levels of neurologic deficit.

1. Opioids. Use of transdermal systems, for example, fentanyl patch should also be continued, although not necessarily initiated. If an opioid-tolerant patient is unable or does not take his pain medication on the morning of surgery, then the patient’s daily opioid consumption should be calculated and converted into the equivalent intravenous morphine dosage. This calculation will provide the anesthesiologist with an approximate idea of the patient’s daily opioid intake, some of which will have to be given intravenously during the surgery. The details of converting the patient’s oral opioids to an intravenous dose is somewhat controversial, however the underlying principle is correct; namely that surgical patients who are opioid tolerant will require opioid dosing based on their previous consumption [9].

Some patients with spinal cord tumors have been taking extremely high doses of opioid medication for an extended period of time. The perioperative period is not an appropriate time to attempt to wean these medications. For patients with drug-seeking behavior, attempting to minimize analgesic consumption in the perioperative period is ill-advised.

2. Adjuncts. Continuation of adjunctive medications like gabapentin is recommended; however, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be discussed with the surgeon because of the potential for postoperative bleeding. Implementing gabapentin therapy immediately prior to surgery is controversial. While gabapentin has been shown to decrease postoperative morphine requirements, effective dosages can be associated with significant side effects, most notably dizziness [10]. A recent study found that beginning a preoperative multimodal regimen of medications, including gabapentin, acetaminophen, and an oral opioid, continued into the perioperative period was associated with better pain control and fewer side effects than intravenous morphine PCA [11].

B. Neurologic deficits. The presence of weakness, paresthesias, and bowel or bladder function should be documented in the preoperative record. The neurologic history will determine how the patient is moved and positioned as well as the quality of the neuromonitoring signals which can be expected.

C. Location and etiology. Some types of tumors may be located at the skull base or cervical cord and/or be associated with a syrinx. In these cases, particular attention should be paid to the stability of the cervical spine and any concerns related to manipulating the cervical spine during endotracheal intubation. The anesthesia team should be aware of the primary cancer when metastatic disease is suspected, including an appreciation for the therapies that have been received to date, including surgeries, chemotherapy, and/or radiation. The presence of metastatic disease in other areas of the body may raise important considerations. Breast and lung cancers may also have concomitant metastases to the brain, potentially resulting in space-occupying lesions. Patients who have undergone breast cancer surgery with axillary node dissection may not be able to have intravenous access or noninvasive blood pressure monitoring on that side.

CLINICAL PEARL

Some types of tumors may be located at the skull base or cervical cord and/or be associated with a syrinx. In these cases, particular attention should be paid to the stability of the cervical spine and any concerns related to manipulating the cervical spine during endotracheal intubation.

D. Multidisciplinary preoperative care. The ideal preoperative preparation would optimize patient outcomes with a multidisciplinary approach. One study reported improved outcomes with active efforts of presurgical rehabilitation. The study protocol included an intensive exercise and nutrition program, and optimization of the analgesic treatment. The early postoperative rehabilitation included balanced pain therapy with self-administered epidural analgesia, doubled intensified mobilization, and protein supplements [12]. In this small study, patients in the intervention group reached the recovery milestones faster than the control group (1 to 6 days vs. 3 to 13 days), and left hospital earlier (5 [3–9] vs. 7 [5–15] days).

IV. Intraoperative management

3

A. Induction and maintenance. The plan for induction and maintenance of anesthesia should be established with respect to the patient’s medical comorbidities and in concert with the neuromonitoring plan.

1. Neuromonitoring. While standard of care for neuromonitoring during spinal cord tumor surgery has not been established, multimodality monitoring with motor evoked potential (MEP), somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP), and electromyography (EMG) is useful and common (see Chapter 26). The use of intraoperative SSEPs, MEPs, and EMG allows for continual intraoperative assessment of the dorsal columns, anterior spinal cord, and nerve roots. In deformity surgery and tumor surgery, several studies have demonstrated that no single modality monitors the entire spinal cord [13,14]. When used in combination with SSEP, MEPs are associated with a higher sensitivity and specificity of motor tract injury than single modality monitoring [15]. Utility of monitoring for spinal tumor surgery in specific includes dorsal column mapping during intramedullary surgery and evaluation of temporary clipping of spinal nerve roots in thoracic tumor resection [16].

The anesthesiologist must be aware of which monitoring modalities will be utilized during the surgery, since each has anesthetic implications.

CLINICAL PEARL

While standard of care for neuromonitoring during spinal cord tumor surgery has not been established, multimodality monitoring with MEP, SSEP, and EMG is useful and common (see Chapter 26).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree