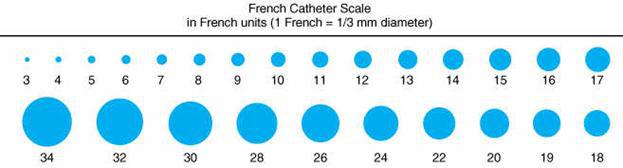

French Size–>

Outside Diameter = OD (mm) X 3 = French Inches / Millimeter.

Outside Diameter = OD (mm) X 3 = French Inches / Millimeter.

1 –> 0.1 / 0.3.

4 –> 0.05 / 1.3.

8 –> 0.1 / 2.6.

10 –> 0.13 / 3.3.

12 –> 0.16 / 4.0.

16 –> 0.21 / 5.3.

18 –> 0.23 / 6.

20 –> 0.26 / 6.6.

22 –> 0.28 / 7.3.

30 –> 0.41 / 10.6.

38 –> 0.5 / 12.6.

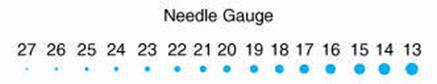

Gauge–> Outside Diameter: Inches / mm.

26 –> 0.018 / 0.45.

26 –> 0.018 / 0.45.

25 –> 0.02 / .05.

24 –> 0.022 / 0.56.

23 –> 0.024 / 0.61.

22 –> 0.028 / 0.71.

20 –> 0.036 / 0.91.

18 –> 0.048 / 1.22.

16 –> 0.064 / 1.62.

14 –> 0.08 / 2.03.

12 –> 0.104 / 2.64.

10 –> 0.128 / 3.25.

Catheter Flushing:

Flushing procedures are necessary before and after the administration of intermittent medications through a capped catheter lumen; before and after blood sampling or the infusion of blood products; before and after the administration of incompatible medications; and when converting a catheter from a continuous to an intermittent infusion. A hospitalized patient will usually receive flushes after each use and at least every 8 or 12 hours. Patients in home care or an ambulatory infusion clinic will have the catheter flushed daily or after each infusion, which could be less frequent than every day.

Dilute heparin: This use to be the standard flush to lock most central venous catheters. The exceptions are valved catheters and needleless connectors that are indicated to be used with saline only. Numerous issues regarding the use of heparin have led to serious concerns in recent years. These issues drive the many questions about the continued use of heparin for catheter-locking procedures, including technology changes, cultural concerns, impact on coagulation laboratory values, drug compatibility, biofilm growth, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and medication errors.

Normal Saline: Accomplished with 0.9% sodium chloride or normal saline. A short peripheral catheter is commonly flushed with a minimum of 2 mL, although a larger volume may be required to assess patency when a vesicant medication must be given. A central venous catheter is longer than a peripheral catheter, requiring a minimum of 5 mL for flushing. Blood sampling from the catheter or blood transfusion through the catheter requires a minimum of 10 mL, although 20 mL is often used. Normal saline is commonly used to lock short peripheral catheters.

Ethanol locks: Can help with preventing catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI). In children with intestinal failure, using ethanol (70% qd, 0.8-1.9ml depending on volume of the lumen and hub) locks instead of heparin (10 units/m) locks on parenteral nutrition central lines might reduce bloodstream infections and catheter replacements (Pediatrics 2012;online January 9)……”Ethanol has two desired effects of a lock solution: it is antimicrobial and antifibrinolytic,” the authors point out.

Drug Compatibility: Heparin is incompatible with numerous other medications….precipitate formation when meperidine, promethazine, hydroxyzine HCl, gentamicin sulfate, tobramycin sulfate, metilmicin sulfate, and amikacin sulfate are administered into a heparinized catheter.

**Ref: (Pulmonary artery catheters in the critically ill. An overview using the methodology of evidence-based medicine. Crit Care Clin 1996;12:777-94) (Cardiovascular-pulmonary monitoring in the ICU. Chest 1984;85:537-668) (Irwin and Rippe’s Intensive Care Medicine, 4th ed., 1999, Lippincott-Raven) (Am Fam Phys 1996;54:3) (Bedside Critical Care Manual, 1998, Hanley & Belfus, pp62-69) (Cardiac complications in the intensive care unit. Clin Chest Med 1999;20:269-85)

Links: Rounds | EMR’s & Note Writing | Admissions | CCU Admit | ICU Notes | Discharge Summary / Note / Planning | SSI | KCl | Coumadin | PAWP | Hospitalist Care | Procedure Note | Surgical Notes / Orders |

Medicaid: a jointly funded, Federal-State health insurance program for certain low-income and needy people.

Medicare: a federal program for health services for the elderly and disabled. See below.

A study concludes that only about 21% of primary care physicians are in practices of sufficient size (11 physicians) to calculate any meaningful differences in cost or quality poses a serious problem for any proposed pay-for-performance scheme (JAMA 2009;302:2444).

A study concludes that only about 21% of primary care physicians are in practices of sufficient size (11 physicians) to calculate any meaningful differences in cost or quality poses a serious problem for any proposed pay-for-performance scheme (JAMA 2009;302:2444).

“SOAP” mnemonic:

S (subjective): observations, pt complaints, e.g., “My chest hurts when I breath”.

O (objective): description of physical findings and recording of laboratory, x-ray, or ECG data:

Blood pressure: 130/80; pulse: 84; respirations: 20; temperature: 38°

Skin: diaphoretic, no rash or petechiae.

Lungs: decreased breath sounds in right base, no rales or wheezing.

Heart: normal S1, S2, without murmurs.

Abdomen: soft, bowel sounds active, no tenderness or masses

Extremities: no clubbing, cyanosis, or edema (C/C/E).

Lab: WBC: 15,900 with shift to left (14 bands, 65 segs).

Pulse oxymetry: 89%.

CXR: right upper lobe infiltrate.

ECG: NSR, no ST changes.

A (assessment) / P (plan): RUL pneumonia. Treat with O2 @ 2 LPM. Ceftriaxone 1 g IV qd + Azithromycin 500 mg IV qd.

Types of Physician Rounds:

Meetings of all members of the service for discussing the care of the patient. Rounds occur daily and are of three kinds.

Morning Rounds: Also known as “work rounds,” morning rounds take place anywhere from 6:00 to 9:00 AM on most services and are attended by residents, interns, and students. Morning rounds are the time for discussing what happened to the patient during the night, the progress of the patient’s evaluation or therapy or both, the laboratory and radiologic tests to be ordered for the patient, and, last but not least, talking with and evaluating the patient. Know about your patient’s most recent laboratory reports and progressthis is a chance for you to look good.

• Ideally , differences of opinion and glaring omissions in patient care are politely discussed and resolved at morning rounds. Writing new orders, filling out consultation forms, and making telephone calls related to the patient’s care are best done right after morning rounds.

Attending Rounds: Attending rounds vary greatly depending on the service and on the nature of the attending physician. The same people who gathered for morning rounds are at attending rounds, as is the attending. At this meeting, patients are often seen again ( especially on the surgical services); significant new laboratory, radiographic, and physical findings are described (often by the student caring for the patient); and new patients are formally presented to the attending (again, often by the medical student).

• The most important priority for the student on attending rounds is to know the patient. Be prepared to concisely tell the attending what has happened to the patient. Also be ready to give a brief presentation on the patient’s illness, especially if it is unusual. The attending will probably not be interested in minor details that do not affect therapeutic decisions. In addition, the attending will probably not wish to hear a litany of normal laboratory values, only the pertinent ones, such as “Mrs. Pavona’s platelets are still 350,000/mL in spite of her bone marrow disease.” You do not have to tell everything you know on rounds, but you must be prepared to do so.

• Disputes among house staff and students usually are bad form on attending rounds. For this reason, the unwritten rule is that any differences of opinion not previously discussed should not be raised initially in the presence of the attending.

Check-Out or Evening Rounds: Formal evening rounds on which the patients are seen by the entire team a second time are typically done only on surgical and pediatric services. Other services, such as medicine, often have check-out with the resident on call for the service that evening (sometimes called “card rounds”). Expect to convene for check-out rounds between 3:00 and 7:00 PM on most days.

• All new data are presented by the person who collected them (often the student). Orders are again written, laboratory work desired for early the next day is requested , and those on call compile a “scut list” of work to be done that night and a list of patients who need close supervision. To comply with the Many services have adopted “night-float” coverage systems. The interns and residents caring for your patients overnight will meet with the team at evening sign-out rounds. These cross-coverage strategies call for clear, concise communication essential during rounds.

Bedside Rounds: Bedside rounds are basically the same as other rounds except that tact is at a premium. The first consideration at the bedside must be for the patient. If no one else on the team says “Good morning” and asks how the patient is feeling, do it yourself; this is not a presumptuous act on your part. Keep this encounter brief and then explain to the patient that you will be talking about him or her for a while. Most patients treated this way feel flattered by the attention and listen with interest.

• Certain points of a hallway presentation are omitted in the patient’s room. The patient’s race and sex are usually apparent to all and do not warrant inclusion in your first sentence .

• The patient must never be called by the name of the disease, eg, Mrs. Pavona is not “a 45-year-old CML (chronic myelogenous leukemia)” but “a 45-year-old with CML.” The patient’s general appearance need not be reiterated. Descriptions of evidence of disease must not be prefaced by words such as outstanding or beautiful. Mrs. Pavona’s massive spleen is not beautiful to her, and it should not be to the physician or student either.

• At the bedside, keep both feet on the floor. A foot up on a bed or chair conveys impatience and disinterest to the patient and other members of the team. It is poor form to carry beverages or food into the patient’s room.

• Although you will probably never be asked to examine a patient during bedside rounds, it is still worthwhile to know how to do so considerately. Bedside examinations are often done by the attending at the time of the initial presentation or by one member of a surgical service on postoperative rounds. First, warn the patient that you are about to examine the wound or affected part. Ask the patient to uncover whatever needs to be exposed rather than boldly removing the patient’s clothes yourself. If the patient is unable to do so alone, you may do it, but remember to explain what you are doing. Remove only as much clothing as is necessary, and then promptly cover the patient again. In a ward room, remember to pull the curtain.

• Bedside rounds in the intensive care unit call for as much consideration as they do in any other room. That still, naked person on the bed may not be as “out of it” as the resident (or anyone else) believes and may be hearing every word you say. Again, exercise discretion in discussing the patient’s illness, plan, prognosis , and personal character as it relates to the disease.

• Remember that patient information with which you are entrusted as a health care provider is confidential. There is a time and place to discuss this sensitive information, and public areas such as elevators or cafeterias are not the appropriate location for these discussions.

Cut and Paste: Most doctors copy and paste old, potentially out-of-date information into patients’ electronic records, according to a study looking at a shortcut that some fear could lead to miscommunication and medical errors (Crit Care Med 2012;online December 20)…..”The electronic medical record was meant to make the process of documentation easier, but I think it’s perpetuated copying,” said lead author Dr. Daryl Thornton of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Using plagiarism-detection software, the researchers analyzed five months’ worth of progress notes for 135 patients. They found that 82% of residents’ notes and 74% of attending physicians’ notes included 20% or more copied and pasted material from the patients’ records.

Experts suggested that copying signifies a shift in how doctors use notes – away from being a means of communication among fellow healthcare providers and toward being a barrage of data to document billing.

“What tends to get missing is the narrative – what’s the patient’s story?”.

Dr. Erickson worries more that repeatedly copying and pasting large chunks of text, possibly along with images and other records, will result in “a long, rambling note that does not make clear points.” “If your communication isn’t accurate, timely, complete and factual, then you really could be transmitting bad information forward that then creates this tumbling effect.”

• An epidemic of computer-induced cognitive drift (CD) is affecting ICU physicians (Kidney Week 2012: American Society of Nephrology 45th Annual Meeting. Abstract FR-PO070. Presented November 2, 2012)….were getting very frustrated with the time delays between the click of a mouse and the time you get to see what you expect to see on the PC screen…..The interval can be as short as 1 second. If the lag is 10 seconds, the authors posited that the user’s attention can be lost completely……for most doctors, more than 10 seconds meant that they would begin to lose focus….CD is common, unreported, and unrecognized as a source of physician stress and causes distraction that can lead to medication errors. The lag time varies, and it can be especially long at night when the systems are doing automatic backups.

At big institutions, a handful of people decide which EHR system to purchase based on “cost and presentation and everything else, and it becomes difficult,” he said. In addition, different parts of different EHR systems may function better or worse depending on the supplier, and different departments may have different needs. So systems are a result of compromise to some degree.

• Information overload can result in missed test results in electronic health record (EHR)-based environments, according to the findings of a cross-sectional survey of primary care physicians at Veteran Affairs (VA) hospitals (JAMA Intern Med. Published online March 4, 2013)…..The PCPs indicated receiving a median of 63 alerts each day, and 86.9% of the respondents considered the number of alerts excessive. In addition, 69.6% of respondents noted that they received more alerts than they could effectively manage. Perceived information overload among PCPs was also related to missing test results that delayed patient care (OR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.37 – 3.52), although the number of alerts was unrelated to either outcome.

Dictation: Radiologists can expect 8 times as many errors in dictated breast imaging reports generated with automated speech recognition software as with conventional transcription, according to a study from Toronto’s Princess Margaret Hospital, Ontario, Canada (Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:923-927)…..Speech recognition software has been popular among cost-conscious radiology services since the mid-2000s. According to its proponents, automated radiologist report generation allows hospitals to reduce their reliance of human transcriptionists, cutting costs and improving report turnaround times…..The findings indicated that 23% of the automated reports contained at least 1 major error, defined as mistakes that affect the understanding of the report. In comparison, 4% of the conventional reports contained at least 1 major error.

Scribes: Allows physicians to spend more time thinking and making decisions, rather than performing more-mundane clerical tasks. At a minimum, scribes can improve quality of life and productivity as well. Scribes assist physicians in a variety of ways, including documenting details of histories, physical exams, and procedures; assisting in discharges; and following up on laboratory and radiographic studies. Use of scribes increases the number of patients seen and the relative value units generated per hour but does not decrease emergency department turnaround time (Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:490)…..Overall, use of a scribe was associated with a mean increase of 2.4 relative value units generated per EP per hour, primarily resulting from an additional 0.8 patients seen per hour.

Ambulatory Care Notes:

The Problem Oriented Medical Record (POMR): A logical and comprehensive approach to record keeping to help monitor the pt’s with continual updating of this “database”. To include anything that requires dx or management or that interferes with quality of life as perceived by the pt. It can be a firm dx, a physical sx, or a social or economic problem. It is any physiologic, pathologic, psychological, or social item of concern to either the pt or the physician that requires ongoing concern or attention. The problem list is changed continually by updated, as new problems are added or old problems resolve. With a consistent format, it is possible to orient oneself rapidly to the most important current problem without forgetting the others. This is not only beneficial to the primary physician, but to enhance communication to on-call, cross cover and specialist who can rapidly scanning the list and thereby can make a more rational decision regarding the current presenting problem.

Examples: Specific dx (diabetes, HTN, inguinal hernia). Abnormal lab test (elevated LFT’s, elevated ESR). Physiologic (jaundice of unknown etiology). A sign (hepatomegaly, edema). A sx (dyspnea, fatigue, cephalgia). Social (marital discord, alcoholic spouse, stress, financial difficulty). Psychiatric (depression, anxiety). Physical handicap (paralysis, amputation). Risk factor (FHx of CAD, DM, colon Ca). Each problem list is unique to that individual. It is a dynamic “snapshot” of that person’s health risks and current and past medical problems. The problem will often evolve over time, such as “knee pain” to osteoarthritis or “dependent edema” to CHF or “atypical chest pain” to GERD. With electronic medical records, the ability to track multiple and complex pt’s is enhanced if one can carry over the past problem list and plan to be updated at the next note as the “assessment – plan”. I would suggest that one also carry over the FHx, Soc, Surg, prevention sections at the same time.

“ADC-VAN DISMEL” –>

Admit to (floor, attending).

Dx:____. Condition (stable, fair, poor, guarded critical).

Vital (routine, q4h, q shift).

Activity (bed rest, OOB to chair, bathroom privileges, bedside commode).

Nursing: I/O, daily wt, call MD.

Diet (clears, regular, no added Na, 1800 ADA, 2gm or 4gm Na+).

IV fluids: (Type at cc/hr or hr rate)

Sensitivity: Allergies (meds, foods).

Meds: (Drug, dose, frequency). PRN Meds: (Mylanta, Acetaminophen, Benzodiazepine, Ambien 5-10mg qHS). MS 1-2mg IV q1-2 (hold RR<12 or somnolence).

Bowel Protocol: Fiber-rich juices (prune), frequent ambulation and hydration. Docusate-Na 100mg PO qd. MOM 30ml qHS PRN constipation. Bisacodyl supp 10mg PRN qd if MOM ineffective. Na-phosphate enema x1 if MOM & bisacodyl ineffective.

Extras: Blood glucose (qAC and HS, If NPO use Q4-6 hours, see SSI scale below).

Alcohol (DT) Precautions: B12 1000ug IM now & in AM. Vit. K 10mg IM now & qAM x3, Folate 1mg PO qd X4, MVI 1 PO qd, Thiamine 100mg IM qd X3. Valium 10mg PO q8hr day1, then 5q8, then 2.5 q8hr. And PRN Ativan:1-2 PO q4-6h PO/IM/ V PRN agitation.

Labs: TSH, CBC, renal, PT/PTT, CXR, U/A, EKG, Ca-Mg-PO4, ETOH level.

Daily X 1 PRN T>101F: blood Cx X2 (or 1 from central line 1 from periphery), UA & C&S, Sputum for G-stain & Cx.

OTHER Various: Daily Flow Loops, Bowel Program, pneumatics leg compression, Lovenox 40 SQ qd or 30 BID. Voldyne (incentive spirometry (ICS) 10X qhr while awake, encourage cough, Fall precautions, OOB in chair/walk QID, Daily wt, call if UO <3/4cc/kg/hr X2hr or if RR>25. NGT to continuous suction. O2 keep SATs >93%. PT/OT/ST eval. DIC screen, ammonia level, amyl/lipase.

NEBS (UDN): Alb 2.5 + 0.5 Atrov + 0.4 Dexamethasone (or Betamethasone) q4h and PRN. P & PD (percussion and postural drainage) with each UDN.

Blood Transfusion: If Hb<7 g/dL, sooner if co-morbid conditions or rapid falling. A reduction of >2 g/dL from previous Hb suggests a major bleed. Type and Cross 2-4 units PRBC’s. Premedicate with diphenhydramine 25-50mg PO/IV + acetaminophen 500-650mg PO/PR. May need 40-60mg IV/PO Lasix 1hr after transfusion complete if at risk of volume overload.

CHF: Lasix 40-80mg q6h IVP, Aldactone 25 qd-BID, ACEi. Dig load 0.25mg IV, then 0.125mg PO qd.

**Rate Control in Afib: Dilt better than Verapamil as less myocardial depression, give at 0.25mg/kg IV over 2min, if no response, give 2nd dose in 10 min @0.35mg/kg, then infuse at 10-15mg.

Admit note:

1. Reason for admission.

2. Other active Dz’s (OADs).

3. Risk factors, health maintenance activities, environmental risks, behavioral / lifestyle risks, disease or tx-associated risks.

4. Social History. 5. ROS. 6. PE.

7. Labs. 8. Problem list. 9. A/p.

Surgical Admit Orders:

Admit to _______________

Resid:_______ PGR#

Intern:_______

Diagnosis:

Condition: Good/stable/fair/critical

Vitals: q 6° (on routine floor) or q 1° (ICU or intermediate care unit)

Activity: OOB ad lib, Restrictions are otherwise pt specific

Allergies: specific or NKDA

Nursing: Strict I/O’s. Pre-Op weight on front of chart. Daily weights. EKG on arrival to floor. CXR on arrival to floor. Pre-Op EKG report to chart tonight. Pre-Op CXR report to chart tonight. Incentive spirometer with Pre-Op teaching

Misc: Is the pt arriving with drains/tubes? Bedside PFT’s? ABG? Accuchecks?

Diets: Regular diet (if no co-morbid conditions and not having bowel surgery) or Clear liquids (if having bowel surgery) or NPO after MN for everyone.

IVF: Hep-Lock IV or Start D5LR or LR at 100 cc/hr 8 hours Pre-Op if surgery will be extensive

Meds: Resume all Pre-Op meds as appropriate. Hold insulin/sulfonylureas if you make pt NPO – cover with sliding scale. Ranitidine or cimetidine PO q HS night of surgery and on call (if GETT).

Labs: CBC, BMP, ECMP, PT/PTT, UA, C&S. Additional labs as appropriate.

Extra: Other X-ray studies. Nuclear medicine studies. Special procedures. Consults. Physical therapy. Occupational therapy. Social services. Consider: DVT prophylaxis. Sleeping medications

Daily Rounds for Trainees:

Prerounds: time you spend seeing your patients on your own before the

team meets. Involves checking vital signs and nursing notes to see if any events occurred overnight. The patients

are woken up and asked how they are feeling followed by specific questions relevant to their main problem(s). A focused examination is performed that includes noting any tubes and infusions. New lab or other test results are recorded. Record all this in the form of a progress note for efficiency and organized oral presentation. Allow 15–30 minutes per patient.

Rounds: time spent reviewing all the patients together as a team. Can be work rounds or teaching rounds.

Work rounds: typically run by the resident and every patient is briefly presented and seen so that plans can be made and orders written

for the rest of the day. Fast paced, presentations should be very focused (1–3 minutes). Sometimes like to “card flip” or have “sit down rounds” as you briefly present and discuss the patients without going to see them.

Teaching rounds: when you formally round with the attending aypically only a few cases are reviewed. Some faculty like to do this at the

bedside and it will likely be the only time you give a full presentation about your patient (refer to oral presentation guidelines above).

Combined work & teaching rounds: the most common format. The attending will join the team for a more extended

round during which all patients are seen, presentations are a bit more formal, and brief teaching points will be made as each patient is seen.

For patients with complex or multiple active problems, most prefer you to present the assessment and plan by problem (i.e., assessment and plan

for their pneumonia, then for their diabetes, then for their DVT, and so forth).

Admit to CCU.

Dx: New onset angina, crescendo angina, R/o CAD, AMI.

Condition: stable.

VS: q2hr X 8, then q4hr.

Allergies:___.

Activity: bed rest with bedside commode.

Nursing: I&O, daily wt, guaiac all stools. No IM injections. Heparin lock, flush q shift. O2 2L NC, humidified. Pulse Ox, record in chart, Cardiac Monitor.

Diet: NPO except meds for cath in AM. Cardiac (or 4g Na, low fat).

Meds: EC ASA 325mg qd, nitro paste 6” q6hr (or drip), Lovenox 40-60mg SC BID or Heparin 5,000U SQ q12hr (if not IV), Docusate-Ca (Surfak): 240mg PO qd, Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) 25mg or Ambien 5-10mg PO qHS PRN, Tylenol 650mg PO q4hr PRN. Alprazolam (Xanax) 0.25-0.5mg PO q6-8hr PRN. (Hold Ca blockers as neg inotropic). Add beta-blocker and ACEi such as Atenolol/ Metoprolol 25mg PO BID, Captopril 6.25mg q8hr.

Lab: Cardiac enzymes q6hrX3 or Troponin qx3 (1st set drawn in ED at__). Chem 18, Mg with next blood draw. UA. Check blood levels of ongoing meds (dig, quinidine, theo, procainamide).

ECG: q AM, check R side ECG on admission (to check lead V4r).

Call MD: PVC >6/min, heart block, HR>100, <50, Pox<93%, T>38.5, SBP>140, <90, DBP>90, <60.

Cost-effectiveness analyses suggest that a CCU is the appropriate triage option for pt’s whose probability of acute MI is >20%, for pt’s whose risks for MI or acute coronary ischemia are lower, admission to telemetry units is often recommended, including a short stay on a chest pain (or coronary) evaluation or observation unit (Ann Int Med 2003;139:897-95).

To CCU if one of the following: substantial ischemic ECG changes in 2 or more leads that are not known to be old (ST elev >1mm or Q’s >0.04s or ST dep >1mm or TWI c/w the presence of ischemia). Any 2 of the following conditions, with or w/o substantial ECG changes: CAD known to be unstable. SBP <100, rales above the bases, serious new arrhythmias (new-onset AF, A-flutter, sustained SVT, 2nd degree or complete heart block, sustained or recurrent ventricular arrhythmias). Patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest admitted to hospitals with a bed-to-nurse ratio <1 were 1.5 times more likely to survive to hospital discharge than those admitted to hospitals with higher ratios (Prehosp Emerg Care 2008;12:339).

To Intermediate unit: Any of the following, but not meeting the criteria of CCU: CAD known to be unstable. SBP <110, rales above the bases, major arrhythmias (new-onset AF, A-flutter, sustained SVT, 2nd degree or complete heart block, sustained or recurrent ventricular arrhythmias). Now-onset typical ischemic heart dz that meets the clinical criteria for unstable angina and that occurs at rest or with minimal exertion.

Evaluation or observation unit: new-onset sx’s that may be consistent with ischemic heart disease but are not associated with ECG changes or a convincing dx of unstable ischemic heart dz at rest or with minimal exertion. Known CAD whose presentation does not suggests a true worsening but which further observation is thought to be beneficial, commonly because a benign dz cannot be established. During continuous ECG monitoring of 6355 patients in the 7 days after randomization, 20% exhibited one or more transient ischemic episodes, and these pt’s were at elevated risk for cardiovascular death (7.7% vs. 2.7%), myocardial infarction (9.4% vs. 5.0%), and recurrent ischemia (17.5% vs. 12.3%) (J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1411).

The most practical note: is to write a “24hr summary”, then list the lines & problems (+ meds), then key physical / labs, then a detailed summary of problems and plan.

The traditional / “In Training Note” is:

“24hr:” (summary of events): talk with the pt’s nurse and the overnight call person.

Lines: condition & day #.

Meds: list all.

Neuro: subjective and exam, pain, mental status, neuro, tremor, intubation, meds = sedation, analgesia, psych, sz, ETOH/ DT precautions, GCS, MAE (moving all extremities).

Resp: subj and lung exam, include resp distress, rate, and sputum production. Vent settings and results, ABG, CXR, ETT size and position, meds = bronchodilators (NEBS = UDN), steroids, theo levels

CV: subj and exam, BP, MAP, HR, rhythm, ectopy, hemodynamics (Swan #’s) and calculations, EKG, cardiac enzymes meds = cardiac meds/ drips (pressers), levels

Renal: subj and exam, fluid status, wt I/O’s, UO, IVFs (type & rate), free H2O, CXR fluid, CVP. BUN/Cr, Alb. K. P, Mg, acid-base status, urine lytes. Meds such as diuretics or dopamine. (Fluids-electrolytes-Nutrition (FEN) –> lytes, nutrition.

GI: subj and exam, bowel function, gas, nausea, diet (TF Vs TPN), NGT, gastric/ bowel contents, abd films, LFTs, pancreatic, PT, meds = H2 blocker, PPI

Heme: subj and exam, skin, bleeding , CBC, smear, coags, transfusions, blood in bank, meds, vit K, SQ heparin, heparin, Coumadin, DDAVP

ID: subj and exam, T, Tmax, skin, decubitus ulcers, WBC, diff, C&S, CXR, UA, lines, meds such as Abx day #, Abx levels.

Endo: glu, TFT, adrenal function, osmolarity, ketones, gap, meds such as insulin, thyroid hormone, steroids.

Assessment/ Plan:.

**Pre-rounding Pearls: 24hr summary, meds, lines, then problems by system. Presenting is often attending specific. 40,000 units EPO SQ qwk starting on day #3 in critically ill pt’s reduces allogeneic RBC transfusions and increases Hb (JAMA 2002;288:2827-35).

Pearls: Proton pump inhibitors may hold some advantage for stress ulcer prophylaxis in the ICU compared with H2-receptor blockers (SCCM 2008 Meeting; Abstract 43)….the PPI esomeprazole kept gastric pH in the safe range 23% more often on the second day and 32% more often on the third day compared with ranitidine….no increased risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia for esomeprazole compared with ranitidine (13.9% versus 17.6% overall, P=0.749).

• In critically ill patients, PPIs are more effective than histamine H2-receptor antagonists in reducing the risk of gastroduodenal stress-related mucosal bleeding, according to a new meta-analysis (Am J Gastroenterol 2012;online January 31)…PPI therapy significantly reduced the incidence of GI bleeding (odds ratio 0.30)….Secondary endpoints of nosocomial pneumonia and mortality were not significantly different with odds ratios of 1.05 and 1.19.

Communication: Families members of critical pt’s want information in an understandable language, honest answers, specific facts about what is wrong with the pt, prognosis for recovery, want to be assured of the pt’s comfort, want to believe that hospital personnel care about the pt, want info from the physician at least qd, want to be called at home about changes in the pt’s status, they want to be comforted, to express emotions and if critical they want to find meaning in the death of their loved one. See “Death and Dying/ Geriatrics” chapter for specific on dealing with families, dealing with death/dying and comfort care.

• Resources used by different physicians in the ICU vary widely without influencing pt outcomes as discretionary ICU costs per day varied by 43% depending on which intensivist guided care (Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:1206-1210)…need to provide uniformly optimal care, possibly by creating a large number of care pathways/guidelines along with a variety of processes and systems designed to ensure their consistent use.

Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD): in one study was shown to reduce mortality, length of stay, the frequency of colonization with resistant bacteria, and the total costs of antibiotic tx in pt’s treated in an ICU when compared with ICU pt’s receiving standard care (in a setting with low prevalence of VREC and MRSA) (Lancet 2003;362:1011-16).

Standard care involved rinsing the mouth 4 times daily with water, tooth brushing BID, the initiation of enteral feeding generally on the first or second day in the ICU, and the initiation of systemic Abx’s for proven or suspected infections.

In the SDD group, pt’s were treated 4 times daily with an oral paste (containing 2% each polymyxin E, tobramycin, and amphotericin B) applied to the buccal cavity; 100 mg polymyxin E, 80 mg tobramycin, and 500 mg amphotericin B through gastric tubes; plus an initial 4-day IV course of 1000 mg cefotaxime. Pt’s with blind bowel loops also received suppositories containing 42 mg each amphotericin B and polymyxin E and 64 mg tobramycin.

Overall mortality in the ICU occurred in 15% of the SDD group (median stay 6.8 days) and 23% of the standard care group (median stay 8.5 days). Overall in-hospital mortality was 24% and 31% in the SDD and standard care groups, respectively. During ICU tx periods, 61 of 378 SDD pt’s (16%) and 104 of 395 standard care pt’s (26%) showed colonization with gram-negative bacteria resistant to ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, imipenem, polymyxin E, or tobramycin. Colonization with vancomycin-resistant enterococcus occurred in 1% of the pt’s in each group and no pt was colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus. The overall total cost of Abx’s was 11% lower in the SDD group compared with the standard care group, primarily due to a decrease in the administration of antifungal tx and Abx’s against gram-negative bacteria.

The d/c summary should contain only essential information regarding the investigation and tx of the pt’s illness.

Pt’s Name:___.

Medical Record Number (SSN):___.

Date of Admission:___.

Date of Discharge:___.

Admitting Diagnosis:___.

Discharge Diagnosis:___.

Attending or Ward Team:___.

Procedures, Diagnostic Tests:___.

HPI: with pertinent PE, and labs.

Hospital Course: including evals, tx’s, meds and outcome of tx.

Discharged Condition: improvement/ deterioration’s and present status.

Disposition: (home, nursing home), who will take care of pt.

D/c Meds (with doses):___.

D/c instructions: f/u appt date, diet, exercise.

Problem List: active (HTN, COPD, DM) & past (s/p or resolved) problems.

Copies: Send copies to attending, clinic, consultants, your file.

Discharge Note:

Written in the pt’s chart prior to discharge, usually instead of a standard note.

Date/time:

Diagnoses:

Tx: brie description of therapy provided during hospitalization, including Abx and surgery.

Studies Performed: ECG, CT etc.

Discharge meds: F/u:

Discharge Planning:

Discharge planning begins on the day of admission. Several steps will speed the process:

• Involve the social worker early (day of admission).

• Establish the goals early and communicate with patients, family, and staff.

• Keep in touch with the family (i.e. are they going to take their loved one back?)….will the patient’s prior living arrangement is safe or is a higher level of ongoing care such as an assisted living facility or SNF required?

• Advance the diet as appropriate. If the patient needs a new, special diet (cardiac, soft or diabetic), a nutritionist should start teaching early.

• Pearls: Get that IV and Foley out ASAP. Do not discharge until approved by the resident. Switch Abx’s to PO or discontinue Abx’s at least 24 hours in advance of discharge. Complete visiting nurse, home TPN, nursing home and other forms ahead of time (i.e. by Friday for a Monday discharge).

• Meds: Establish a complete an accurate outpatient medication list at the time of admission. Verify that patients are actually taking these medications outside of the hospital. Discontinue medications that are no longer indicated. Plan necessary lab monitoring and follow-up of new medications after discharge. Provide a complete, up-to-date, and accurate medication list to both the patient and the primary care physician at the time of discharge. Rx 30 day supply of any new prescriptions if appropriate.

• Arrange a follow-up appointment. Discuss the plan with the patient’s outpatient provider, who can often follow up on most medical issues. If consultants have been involved in the patient’s in-hospital care, ask whether subspecialty follow-up is needed and in what time frame.

Steps guaranteed to delay or scuttle discharges: CXR or labs on the day of discharge. Not keeping in touch with family.

• Delayed discharge summary creation and lack of training are associated with omissions (J Gen Intern Med 2011:Sep 7;e-pub ahead of print)…..actionable items such as diet, activity instructions, and therapy orders were included in only about 50% the summaries….Completion of discharge summaries >24 hours after discharge predicted that fewer actionable components would be included. Discharge summaries completed by interns, when compared with those completed by more-senior residents or attending physicians, also predicted lower rates of inclusion for plan-of-care components.

Nursing Home / Rehab Center Transfer Guidelines: Anticipate and note in the chart the orders a day or two in advance. Dictate as a “transfer summary”. When ready to go, just write the order “discharge today”. When dictating the med list, must include a dx for each med and include a additional handwritten Rx for any narcotic. Be sure to include either pt’s code status and document the managing provider and ensure that that provider knows the pt is being transferred. Call the accepting physician.

Bounce-Back / Hospital Re-admissions: Rehospitalization rates among Medicare beneficiaries were found to be unacceptably high in a fee-for-service program (NEJM 2009; 360:1418)…..20% of older hospitalized patients were readmitted within 30 days, 34% returned within 90 days, 45% returned within 180 days, and 56% returned within 1 year……Researchers found no charges for outpatient physician visits for 50% the patients who were rehospitalized within 30 days (after medical discharge to the community)…..Diseases associated with the highest 30-day rehospitalization rates were congestive heart failure (27%), psychoses (25%), vascular surgery (24%), and COPD (23%)…..A large percentage of bounce-back admissions appear to be related directly to poorly coordinated transitions of care…….tremendous improvement might be possible if patients were seen by their primary care physicians within a few weeks after discharge.

• A study found that discharging and readmitting physicians communicated on only about half the patients who returned within 2 weeks (J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:374).

• Rapid outpatient follow-up (within 7 days) of discharged heart failure patients was associated with fewer hospital readmissions (JAMA 2010;303:1716)…..Heart failure patients might be particularly susceptible to rapid hospital readmission, because they often have substantial medication changes during hospital stays and might require rapid clinical assessment and laboratory follow-up.

A standardized discharge intervention lowered the incidence of rehospitalization within 30 days by 30% according to a RCT on 749 patients (Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178)…..Estimated total direct cost savings for the intervention was US$149,995 — an average of $412 per person who received it. The intervention had three main components:

1. Nurse discharge advocates who coordinated discharge plans with the hospital team and educated and prepared patients for discharge

2. After-hospital care plans (also coordinated by the discharge advocate), which contained reasons for hospitalization, discharge medication lists with instructions, contact information for discharge advocates and primary care providers, appointment calendars, and lists of pending tests

3. Follow-up phone contact by clinical pharmacists at 2 to 4 days after discharge to reinforce discharge plans and to address any medication-related problems.

Discharge Problems: About 1 in 5 patients discharged home experiences an adverse event, complication, or problem within 72 hours a multicenter study has found (Hospital Medicine 2009: Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Annual Meeting: Abstract 607215. Presented May 16)……adverse events included the patient not having a follow-up appointment scheduled, waiting for test results, not receiving an explanation of how to work home healthcare equipment, having symptoms that were new or that concerned the patient, and having medication problems…..Patients who reported any postdischarge adverse event were slightly more likely to be rehospitalized within the first month than those who did not (6.1% vs 5.6%), and were significantly more likely to be rehospitalized if the event was related to medication (11.8% vs 9.8%)…..”If we’re going to target the elderly with a follow-up phone call after discharge, we may have to work extra hard [at finding potential problems].”

Discharge communication software with computerized physician order entry (CPOE) may improve patient and outpatient physician satisfaction at hospital discharge, according to the results of a cluster randomized controlled trial (J Hosp Med. 2009;Published online July 17)……Compared with patients whose inpatient physicians were randomly assigned to usual care (handwritten discharge), those assigned to discharge software had higher mean scores for discharge preparedness and unchanged patient scores for satisfaction with medication information. Their outpatient physicians scored higher-quality discharge.

Link: General Info | Handoff / Transfer of Care & Med Error Issues |

The percentage of general internists who were identified as hospitalists tripled during the past decade and now approaches 20% (NEJM 2009;360:1102). A meta-analysis concluded that faulty communication between hospital-based and primary-care physicians may disrupt proper care of a quarter of pt’s when they are discharged (JAMA. 2007; 297:831-841)….discharge summaries for hospitalized pt’s are often late or incomplete. Even when the summary does show up, it often lacks important information, such as diagnostic test results, discharge medications, or a follow-up plan, the investigators said . Hospital and primary care physicians rarely communicated directly (an average of 3% to 20% of cases, depending on the study). The discharge summary was not usually available at the first post-discharge visit (12% to 34% of visits). Diagnostic test results (missing from 33% to 63% of summaries). Tx or hospital course (7% to 22%). Discharge medications (2% to 40%). Test results pending at discharge (65%). Pt or family counseling (90% to 92%). Follow-up plans (2% to 43%).

“Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based physicians and primary care physicians are substantial and ubiquitous.” “The traditional methods of completing and delivering discharge summaries are suboptimal for communicating timely, accurate, and medically important pt data to the physician who will be responsible for follow-up care.” See Discharge Summary / Note / Planning |

Computer generated summaries were more likely to arrive on time and to include important items such as main discharge dx, radiology test results, laboratory test results, discharge medications, and pending test results. Advise pt’s to make sure hospital-based physicians have correct contact information. Advise pt’s to request a discharge letter from their hospital doctor on the day of discharge. For pt’s with common inpatient diagnoses, the hospitalist model reduces length of stay (-0.6 days vs general internists) and costs (~$400) without adversely affecting mortality or readmission (Hospital Medicine 2007: Abstract 40. Presented May 23-25, 2007).

• In-hospital care by a full-time hospitalist helps reduce lengths of stay (5.01 versus 5.87 days) at teaching hospitals, particularly among pt’s who need specialized services (Arch Intern Med 2007;17:1869-1874)….”a ‘traditional’ doctor visits the hospital once or twice a day while a hospitalist is present all of the time.” Hospitalists shortened inpatient stays modestly and cut costs only slightly compared with care directed by general internists, but these savings were no better when care was managed by family physicians, a study found (NEJM 2007;357:2589-2600).

• For people with pneumonia or heart failure, it appears that greater fragmentation of care results in longer length of stay (J Hosp Med. 2008;3(suppl 1):11)…”some physicians might feel more comfortable watching patients who are new to them for an extra day or so because you don’t know what the previous day was like.”

Mini-rounds: a series of short pt encounters [each lasting about a minute] during which the physician asked pt[s about] any changes in their condition and provided a concise daily update. Mini-rounds appear to be an effective and time-efficient method for improving physician–pt communication and satisfaction (Hospital Medicine 2007: Abstract. Presented May 23-25, 2007)…..Average duration of mini-rounds was 20 minutes to see 15 pt’s in the hospital and 30 minutes to see 30 pt’s at the subacute facility.

Emergency department boarding: inpatients in the ED awaiting a hospital bed assignment. In this retrospective chart review of 151 ED-boarded patients who were admitted to a single tertiary care hospital in Boston during 3 days in 2003 found that 28% had at least one undesirable event (Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:381)……88% were deviations from hospital-based standards, mostly missed home medications (61%), and 12% were adverse events; no deaths or aspirations occurred…..Age >50 and presence of multiple comorbidities were associated with increased frequency of undesirable events.

Medication List Obtained Often Inaccurate: A study with 1797 adult patients found that lists for 38% of patients at a single emergency department omitted medications (28%) or included discontinued medications (10%) (Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:102).

Info: Patients admitted to hospitals with a bed-to-nurse ratio <1 were 1.5 times more likely to survive to hospital discharge than those admitted to hospitals with higher ratios (Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12:339). Nearly 80% of patients did not understand some aspect of their ED care, usually discharge instructions, and most patients were not aware that they did not understand according to a prospective study conducted at two EDs on 140 patients (Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:454)…..Asking them if they have any questions might not be enough….Perhaps we should ask patients to explain their diagnoses and treatment and follow-up plans to us in their own words.

• Physician and patients’ perception of medical knowledge and care appear to differ dramatically according to a survey (Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1302-1307)……”An apparent discordance of opinion exists between patients and physicians regarding many elements of hospitalization,” the authors write…..Three fourths of the patients thought that they had 1 main physician, but only 18% could name that physician compared with 67% of physicians who guessed that patients knew their names (P < .001). Likewise, 77% of physicians believed that patients knew their diagnosis, but only 57% of patients in fact did know their diagnosis on the day of discharge (P < .001).

Disease-specific order sets constitute a clinical decision support tool that is gaining popularity in hospitals. Compared with free-text orders, order sets provide prompts to facilitate evidence-based care. The true value of order sets in improving physicians’ adherence to best-care practices and, hence, in improving patient outcomes, still is being established. A study, performed at a 750-bed community hospital in Ontario, Canada examined whether diagnosis-specific order sets affected use of prophylaxis for DVT found that adherence to order sets rose (52% of admissions), as did DVT prophylaxis (44%) (J Hosp Med 2009;4:81).

In-Hospital Mortality: High hospital volume has been linked to superior patient outcomes for a variety of surgical procedures. Hospitals with low and high perioperative death rates have surprisingly similar rates of perioperative complications, which suggests that “failure to rescue” is the primary determinant of in-hospital mortality (relies on timely recognition and effective management of that complication)(NEJM 2009;361:1368).

• Every year, 48,000 Americans die of infections they caught while in the hospital a study finds (Arch Internal Med 2010;170:347-353)…..Hospital acquired infections actually kill three times more Americans than HIV does.

• Patients admitted to high-volume hospitals for specific conditions are less likely to die (acute myocardial infarction, OR = 0.89, heart failure, OR = 0.91, and pneumonia, OR = 0.95), but a threshold volume exists (NEJM 2010;362:1110)….The volume effect was greatest in small-volume hospitals and was least in large-volume hospitals. …the annual volume thresholds above which 100 additional patients were no longer associated significantly with lower odds of death: 610 for patients with acute myocardial infarction, 500 for patients with heart failure, and 210 for patients with pneumonia….in teaching hospitals these thresholds were significantly lower: 260, 148, and 37, respectively.

• A low hospital surgery volume is associated with a higher risk for venous thromboembolism (OR = 2) and 1-year mortality (OR = 2.1) after primary elective total hip or total knee arthroplasty (THA/TKA) according to the results of a large database study (Arthritis Rheum. Published online June 7, 2011)……based on annual THA/TKA procedure volume of 25 or less…..High-volume hospitals were defined as those performing more than 200 procedures per year.

• Patients who had total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) at hospitals in which fewer than 200 such procedures are performed per year are significantly more likely to die within 1 year after surgery and/or 2.0–3.4-fold higher odds of having a venous thromboembolism within the 30 days after surgery than those patients treated in high-volume hospitals according to an analysis of 29,000 patients (Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2531-2539).

Rapid Response Teams (RRT):

An RRT, also known as a medical response team or medical emergency team, is a multidisciplinary team most frequently consisting of ICU-trained personnel who are available 24 hours per day, 7 days per week for evaluation of pt’s not in the ICU who develop signs or symptoms of clinical deterioration. The goal is to address hospitalized pt’s who demonstrate a deterioration in vital signs with a medical emergency team approach before the pt has a cardiac arrest or other adverse event. Usually a respiratory therapist + hospitalists + CCU RN or ICU MD + RN team or ICU RN + respiratory therapist team. Criteria to call the RRT include a acute change in vital signs (pulse, BP, RR), acute drop in O2 sats, decreased urine output, altered mental status or other staff member concern (www.IHI.org). Implementation of a RRT was associated with a statistically significant reduction in hospital-wide mortality rate and code rate outside of the pediatric ICU setting (JAMA. 2007;298:2267-2274)….mean monthly mortality rate decreased by 18% and the mean monthly code rate per 1000 admissions decreased by 71.7%. Rapid response teams, despite their wide popularity with health-quality advocates, lack data to support their worth, according to a meta-analysis (Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(1):18-2)…..On the surface, the basic premise of RRTs is logical. If a deteriorating patient can be identified promptly and a specialized team can be sent to the bedside, early intervention might prevent a critical event…… Hospitals are consuming scarce resources by promoting an intervention that might not benefit patients as much as would other evidence-based interventions (e.g., improving hospitalist and nurse patient–staff ratios, hiring discharge coordinators).

Other: A study at a single academic ED shows that the practice of admitting boarder patients to inpatient hallways is safe (Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:487)….these are patients who did not require ICU or step-down care or high-intensity nursing care for such needs as continuous suction, high-flow O2, or seizure monitoring were eligible to board in inpatient hallways…..25% were placed in a room within 1 hour, and the remaining 50% waited approximately 8 hours for a room.

• Men have higher rates of hospital utilization within 30 days of discharge than women do (BMJ Open 2012;2:e000428)……Men returned to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days after index discharges at a rate of 47 times per 100 people monthly, whereas women returned at a rate of 29 times per 100 people monthly (incidence rate ratio, 1.62)……predictive factors for hospital utilization among men were single marital status, depressive symptoms, retired employment status, and no primary care follow-up within 1 month.

Explanation to Patients: Traditionally, primary care physicians such as internists and family practitioners have tended to their patients both inside and outside of the hospital. Delivering care in two settings, and doing both well, isn’t easy. Commuting between the office and the hospital creates obvious logistical problems, and working out of two locations makes it impossible for primary care doctors to be available to their hospitalized patients all of the time. Because they often aren’t on hand when problems crop up, emergencies may have to be dealt with over the telephone or handled by doctors-in-training who staff the hospital. As medical care has become increasingly more complex, some doctors have found they can’t keep up. Caring for patients in both the in-patient and out-patient settings simply requires knowing too much. The skill set is very different, it’s not realistic to think that you can be good at both. Hospitalists are on site round-the-clock and are readily available to patients. Because they focus exclusively on caring for the sickest patients, hospitalists are expert at it. It’s a case of practice makes perfect. Hospitalists help reduce medical costs by modestly shortening hospital stays as they adhere to established treatment guidelines more closely than their primary care counterparts.

Teaching vs. Nonteaching Hospitals: Which Are Better?: Compared with nonteaching hospitals, U.S. teaching hospitals deliver higher quality and more-complex care for many conditions, but patient satisfaction is lower (Acad Med 2012;87:701). Teaching hospitals provide care for the most-complex patients and the urban underserved population, train the next generation of physicians, and advance biomedical research. Findings showed that teaching hospitals more often are located in urban areas, represent the majority of level 1 trauma and transplant centers, and have higher case-mix indices. Mortality from acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, and pneumonia were lower at teaching hospitals, whereas readmission rates for pneumonia and AMI were higher. Teaching hospitals more often were adherent to Leapfrog standards. Costs of care were similar between teaching and nonteaching hospitals after adjustment for geographic cost of living, patient complexity, and indigent populations. However, patient HCAHPS satisfaction scores consistently were lower at teaching hospitals…..this might stem from a variety of factors, including the larger number of clinicians involved, higher expectations for tertiary care, and larger hospital sizes.

Avoiding Malpractice Risks in the Patient Handoff:

“Achilles’ heel” and “time bomb” are metaphors used to describe the handoff, that transition when patients are transferred from one doctor to another, or from an outpatient setting to a hospital or nursing home. Problems with handoff communication are listed as one of the root causes in up to 70% of adverse sentinel events compiled by the Joint Commission. Sometimes, test results aren’t available until after the patient has left the hospital.

Good handoffs are about best practices, and about being a good doctor. Investing time in them is the right thing to do. Handoffs are a two-way process, and missed opportunities to impart important patient information result in more uncertainty for the incoming doctor which in turn leads to indecision which can ultimately result in significant delays during critical medical decisions.

• An estimated one in four patients admitted to a hospital in America will suffer some form of unintended harm, and more than 500 people die from hospital mishaps every day. Moreover, an estimated 80% of serious medical errors involve miscommunication between caregivers when patients are transferred or handed off. Good team communication is life or death for patients.

Poor Sign-Outs = Worse Outcomes and Wasted Time. A prospective observational study reveals that inadequate sign-outs are common and have a negative effect on patient care (Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1755)……the authors recommendationr standardization of the sign-out process.

“HANDOFFS” mnemonic for Transfering Care:

H—Hospital location (bed, room).

A—Allergies / medications.

N—Name (age) / number.

D—DNR (code status) / diet / DVT prophylaxis.

O—Ongoing medical / surgical problems.

F—Facts about this hospitalization.

F—Follow-up on…(labs, consult).

S—Scenarios (possible anticipated problems and what to do) (McDonough & Larson: Manual of Evidence-Based Admitting Orders and Therapeutics, 5th ed. 2006 Elsevier).

Barriers to Communication Between Hospital and Nursing Home at Time of Patient Transfer: The most frequently reported perceived barriers to communication were sudden or unplanned transfers (44.4%), transfers that occur at night or on the weekend (41.4%), and hospital providers’ lack of effort (51.0%), lack of familiarity with patients (45.0%), and lack of time (43.5%)(JAMDA 2010;11:239-245)……Increased hospital size, teaching hospitals, and urban nursing home location were associated with greater perceived importance of these barriers, and cross-site staff visits and hospital provision of laboratory and pharmacy services to the nursing home were associated with lower perceived importance of these barriers.

Medication Errors: Perhaps a new lab finding changes the diagnostic picture or the patient’s medication regimen. Maybe an x-ray was misinterpreted. If something is outstanding, it’s the hospitalist’s responsibility to find it out and transmit it to the primary doctor. Many physicians really don’t know what medications their patients are taking. Then they come to the hospital and are put on different meds.

• An observational study reveals that many hospitalized patients have their longstanding medications inadvertently discontinued on discharge (JAMA 2011;306:840)…..The highest adjusted odds ratios for discontinuation were for antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents among hospitalized patients as a whole (AOR, 1.86) versus controls and for levothyroxine among ICU patients (AOR, 1.29) versus hospitalized non-ICU patients. Secondary analyses showed that statin and antiplatelet and anticoagulation cessation each were associated with excess risk for adverse events (death, emergent readmissions, or emergency department visits).

Reconciliation involves 5 steps:

* Develop a list of current medications;

* Develop a list of medications to be prescribed;

* Compare the medications on the 2 lists;

* Make clinical decisions on the basis of the comparison; and

* Communicate the new list to appropriate caregivers and to the patient.

Practical suggestions:

* Create a specific standardized checklist for each type of handoff. These checklists can include major diagnosis, recent procedures, medications, names and numbers for all preceding caregivers, who received the patient as a handoff, and all pending labs/images with contact information.

* Keep the communication of the handoff focused on important issues.

* Preferably communicate with the next provider face to face.

* Limit interruptions.

* Avoid diluting the message, and be sure that the people who need to know are in the know.

* Use a common communication style throughout your system.

* Identify potential complications and “if/then” strategies.

* Ask for “read-backs” to confirm that the information is received and understood.

Medical Errors During the Transition from ED to Inpatient Care: (Ann Emerg Med 2008 Jun 16;e-pub ahead of print) Communication failures between EPs and admitting physicians were attributed to inaccurate or incomplete information (especially about vital signs), cultural or professional conflicts, crowding, high workload, difficulty in accessing key information, patient flow (e.g., “boarding” in the ED), and difficulty identifying providers responsible for sign-out or follow-up.

• A study in two academic hospital centers in the U.S. finds that medication errors after discharge for treatment of cardiovascular disease are common and that a pharmacist-based intervention to address the problem may have little benefit (Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):1-10)…..The incidence of medication errors at 30 days did not differ significantly between the groups (about 50% in each). Roughly 75% of errors were characterized as “significant” in severity, 23% as “serious,” and 2% as “life-threatening.” Examples of adverse drug events included a patient found to have an INR higher than 14 at 8 days after discharge, and a patient whose insulin dose was poorly managed, resulting in several episodes of hypoglycemia.

Notes: In a study that flies in the face of common sense, sicker patients fared worse under the care of seasoned doctors than when younger doctors (licensed in the past five years) looked after them (Am J Med 2011;online July 11th)……compared to patients with the newest doctors, those with the most experienced physicians had more than a 70% increase in their odds of dying in the hospital and a 50% increase in their odds of dying within 30 days…….physicians with more time in practice are less likely to adhere to practice guidelines…….more experienced doctors might have given the residents more autonomy…….the varying lengths of stay could reflect a cultural difference in today’s younger physicians, who are taught to focus on reducing hospital stays.

• Putting children’s photos in their electronic hospital charts could help reduce one type of medical error (getting a test or treatment intended for someone else because the doctor mistakenly put an order in the wrong electronic chart) (Pediatrics 2012;online May 11)…..Doctors may put an order in the wrong record if, for instance, they have multiple records on their screen at a time. “You can think you’re in one person’s chart, but really be in someone else’s.” One issue that can come up, he noted, is that parents sometimes do not want their child’s picture taken. “Some parents don’t want it because of privacy issues, but they should know that we’re doing it for their (children’s) safety.”

List of Never Events covered under the FY 2009 provision: Object left in patient during surgery. Air embolism. Blood incompatibility. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Pressure ulcers. Vascular-catheter-associated infection. Surgical site infection (specifically mediastinitis after coronary artery bypass graft surgery). Hospital-acquired injury due to external causes (fractures, dislocations, intracranial injury, crushing injury, burns, and other unspecified effects)

Unprofessional behaviors in hospitals: (J Hosp Med 2012;June 3) According to a survey on 77 hospital-based doctors in the Chicago area: Three out of 10 said they made disparaging comments about a patient on rounds. 29% said they had attended a dinner or social event sponsored by a drug or medical device manufacturer or other business that stood to gain by a doctor’s decision. 9% admitted that they had transferred a patient they could have taken care of to another in order to reduce their patient load. This practice is known as turfing, and 12% of physicians admitted they had “celebrated” a successful turf. 8% of doctors said they had blocked a patient, which means they refused to accept the patient into their unit by claiming the patient should be cared for in another part of the hospital. 21% acknowledged celebrating a blocked admission. The study noted that “participation in egregious behaviors, such as falsifying patient records (6.49%) and performing medical or surgical procedures on a patient beyond self-perceived level of skill (2.60%), was very low.” But more hospitalists reported seeing another doctor act unprofessionally than admitted they did so themselves. For instance, 68% said they had witnessed another doctor “blocking” a patient–eight times as many who admitted doing the blocking. And almost 20% of doctors said they had observed a patient being discharged before they were ready to go home, while only 2.6% admitted to doing that. Dr.Vineet Arora, one of the authors of the study, said observations of unprofessional behavior can be wrong because doctors don’t “know the full context of the story” or because more than one doctor can report seeing the same incident, inflating the number.

• Predicting 30-Day Readmissions The “HOSPITAL” score algorithm identified about a quarter of those patients at high risk for readmission (JAMA Intern Med. 2013;online March 25)….patients “who may need more intensive transitional care interventions,” according to the authors. The HOSPITAL score: h emoglobin at discharge, discharge from an o ncology service, s odium level at discharge, p rocedure during the index admission, i ndex t ype of admission, number of a dmissions during the last 12 months, and l ength of stay. In the validation set, 26.7% of the patients were classified as high risk, with an estimated potentially avoidable readmission risk of 18.0% (observed, 18.2%). The HOSPITAL score had fair discriminatory power (C statistic, 0.71) and had good calibration.

Sliding Scales:

<3.8 give 20mEq KCl QID

3.9-4.3 give 20 TID

4.3-4.6 give 20 BID

If Mg <1.9 give 2g IVPB.

***If INR: Coumadin: **** (for initiation changes only)

>2.3 0

2-2.3 2mg

1.7-2 3mg

1.4-1.7 5mg

<1.4 6mg. Overall this is not very practical as large pt variation.

PAWP: Not useful in all situations, only as a general guideline.

If <10 and SBP >=100–no change.

If <10 and SBP <100—250 NS and re-check .

If >14 and UO >+100ml/hr—decr IVF to TKO.

If >14 and UO <100ml/hr—decr IVF to TKO and give Lasix 80mg IVP q6h PRN.

CVP: If >8 give Lasix 80mg IVP q8h.

Furosemide dose CHF outpatients based on daily wt:

Ex: At target wt: 20mg.

2lb (1kg) over: 40mg.

4lb (2kg) over: 80mg.

Adjust based on pt’s response.

Date and time:

Procedure:

Indications:

Consent: indications, risks and alternatives explained to the pt. Note that the pt was given the opportunity to ask questions and that the pt consented to the procedure in writing.

Lab tests: Relevant pre-labs (INR and CBC etc.).

Anesthesia: local with 2% Lido.

Description: sterile technique, anesthesia method and amount, pt position, devices used, outcome, complications, estimated blood loss (EBL), how the pt tolerated the procedure.

Specimens & Labs ordered:

Pre-Op Note: See Admit Notes | Bowel Prep |

P2-SALE-BOC –> Pre op dx, Planned procedure, surgeon, allergy, labs, ECG/CXR, Blood, Orders, Consent.

Post-Op Note:

P3 SAFE DCS2 –> Pre op dx, Post op dx, Procedure, Surgeon, Anesthesia type, Fluids, EBL, Drains, Complications, Specimens, Status.

Post-Op – Advancing Diets: As a part of rounds, all of the postop abd surgery pt’s are asked about the status of their intestinal track. “Have you passed gas today? Have you had a bowel movement? As the postoperative ileus resolves, with the colon coming back on line last, the diet is advanced. Most pt’s will be started on clear liquid sips. If the sips are tolerated, the diet becomes clear liquids and the IV is heparin locked. Generally most IV medications will be switched to oral within a day. After 24 hours of clears and the passage of flatus, most pt’s then are advanced to a regular diet. For any bump in the road, you generally fall back a step. If regular is not tolerated, try clears. If clears are not tolerated, it’s back to the IV.

Post op Orders:

ADC-VAN DISMEL –> Admit to, Dx, Condition, VS, Activity, Allergy, Nutrition (NPO, I/O, daily wt), Drains, IVF, Meds, Extras, Labs.

Post-Op Vent Settings:

Step 1: Discuss with your resident anticipated ventilator settings.

Step 2: Order a stat portable CXR and a stat ABG on admission to PACU and ICU.

Step 3: Initial Settings (plan to change them with ABG):

Mode: SIMV (Synchronized Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation).

Tidal Volume: 10-12 mL/kg e.g. 800m1 in a 70 Kg person (dial down if peak pressures high, right main bronchus intubation causes high peak pressures). Rate: 10-14 breaths/min.

FiO2: 100% taper rapidly to 40% once you have the ABG.

PEEP: None. (Peep starting at 2.5 cm H2O and increased by 2.5cm to 10cm may help pulmonary edema and ARDS.)

Set by the Respiratory Tech: Inspiratory flow – 50 L/min. I:E ratio – 1:2. Peak Pressure – 50cm H20. Humidifier Temp 35ºC.

Step 4: Look at that CXR – where is the end of the ET tube? Ideally 5cm above carina. Check that blood gas.

NG tube placed when pt intubated (especially helpful if the pt is bagged prior to intubation.) Check placement. Continuous pulse ox. Consider End-tidal CO2 monitor.

Surgical Daily Progress Note:

POD # and dx, Abx day #, pt c/o, vitals with Tmax and time, I/O’s, drains, PE of CV, lung, abd (BS, flatus, BM). Assess: POD #, on Abx, Plan to follow Cx, ambulate.

Each day ask yourself: Has my pt passed flatus, had a bowel movement? Can I switch my pt to IV maintenance fluid or discontinue it all together? Can I lower or discontinue the oxygen? Can I stop the perioperative Abx’s? Can I advance the diet? Can any IV drugs be made PO, e.g. H2 blockers, digoxin, Abx’s? Are there any medications that I can stop entirely? Do I need to check drug levels? Why isn’t this pt out of bed today? Can I get the Foley or any other tubes out? Did I look at the wound? Is it time for sutures or staples to come out? Why does the pt still need to be in the hospital? (social, medical, rehab)? Do I need to talk to the resident? Social worker?

Example of Op Note Dictation:

Plan to dictate any case where you have a significant role. If it is unclear, ask who is to be considered first assistant surgeon. Clarify specimens, findings and dx before dictating. Anesthesia will provide an estimate of total fluids in and out as well as blood loss. Sample dictations for an inguinal hernia repair, an appendectomy, and a breast biopsy are provided on the following pages.

This is Dr.__________________ dictating an operative note on

Last name:

First name:

Medical record number:

Age:

Service:

Nursing Unit:

Date of surgery: Date of dictation:

Surgeon: (this is the attending): 1st Assistant: 2nd Assistant:

Preoperative dx:

Postoperative dx: same or describe

Anesthesia:

EBL:

IVF:

Specimens:

Drains: (Describe their location)

Indications/ Significant History:

Description of Operative Procedure/Findings:

1. Position.

2. Prep and draping.

3. Incision, course of the dissection.

4. Describe pathology.

5. Therapeutic approach.

6. Location of drains.

7. Instrument, sponge, and needle counts.

8. Pt status.

Findings:

Complications:

This is the end of the dictation on pt name, medical record number by Dr.__________ Thank you.

Harmonic Scalpel (HS): an instrument that uses vibration at 55.5 kHz (i.e, mechanical action) to simultaneously cut and coagulate tissue. The main advantages of ultrasonic coagulating/dissecting systems compared with a standard electrosurgical device are represented by minimal lateral thermal tissue damage (the HS causes lateral thermal injury 1-3 mm wide, ~ half that caused by bipolar systems), less smoke formation, no neuromuscular stimulation, and no electrical energy to or through the pt. Use of a harmonic scalpel (HS) reduced postoperative pain and drainage volume in pt’s undergoing a thyroidectomy (Arch Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:1069-1073), according to the results of a randomized controlled trial reported in the October issue of the Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Mechanical bowel preparation (2 to 4 liters of PEG bowel lavage solution with bisacodyl or Na-phosphate solution, with a fluid diet the day before the operation [beverages, yogurt, and soup]) for elective colorectal surgery may not be necessary, according to the results of a multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial At 13 hospitals with 1431 patients (Lancet. 2007;370:2073-2075, 2112-2117)….Patients assigned to no bowel preparation had normal meals before the operation….Patients who undergo mechanical bowel preparation before elective colorectal surgery vs those who do not undergo preparation have similar outcomes of anastomotic leakage, wound infection, mortality, length of hospital stay, and fecal contamination but a lower rate of abscess after anastomotic leakage….Predictors of anastomotic leakage after elective colorectal surgery are type of anastomosis, ASA classification, and blood loss during the operation.

Withdrawing / Withholding Life-Sustaining Therapy:

Links: Why | When | What | Talking to Family | Withdrawing from Ventilators | Terminal Sedation | Refusal | Food – Hydration, Dialysis, ICD & Other |

This is not the same things as euthanasia, which is actively seeking to end the pt’s life. The decision to withhold tx allows the disease process to progress on its natural course and the intent is to secure comfort, not death. The decision is influenced by the clinical course of the illness, presumed quality of life of the pt and the pt’s medical condition.

To help the family cope, promote an ideal physical environment: allow them to personalize the pt’s environment with family pictures, afghans, religious ornaments, personal pillow, music from home. Encourage family dialogue with/about the pt (tell family stories). Provide the family privacy with the pt so that personal words can be expressed. Keep tissues and chairs at the pt’s bedside. Remain in visual contact but outside hearing range in case the family needs support.

Promote optimal communications: Carefully listen to family members. Share info in a timely manner, explain all procedures in lay terms. Help the family understand prognostic information. Anticipate that some family members may respond with anger, emotional outbursts and temporary inconsolable grief. Ascertain whether family members want to be present during withdrawal tx.

1. The therapy has no hope of meeting long-term tx goals.

2. The tx has failed and its continuation interferes with the optimum care of the dying.

3. To comply with the autonomous decision by the pt or appropriate surrogate. If consistent with pt’s advanced directives. If no advanced directives interview the family to determine the basis of the request/ whether all immediate family members concur. Have them draft a letter of request on the pt’s behalf expressing clear and convincing evidence of the pt’s wishes. For families, the decision to stop a tx tend to be more emotionally wrenching than the decision not to begin it. Fewer than 10% of ICU pt’s are able to participate in their own tx decisions except via advanced directives. Accurate estimates or death are difficult (best to give estimate in minute-hours, several hours, hours-days). Only 8% of pt’s whose life support is withdrawn survive to leave the ICU, 1% make it to hospital discharge.

When: When hope for recovery is outweighed by the burdens of continued tx, best guided by the interests and wishes of the pt.

What: Blood products, hemodialysis, vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, TPN, Abx, IV fluids, enteral feeding. Review the need for routine vital signs, labs, daily wt, X-rays.

Give careful attention to skin, perineal and mouth hygiene as well as to the tx of pruritus, nausea and dyspepsia.

Prognosis in ICU: Physicians’ prognoses are desired and discounted at the same time according to a study that interviewed 50 surrogates for 50 patients in intensive care units (Crit Care Med 2008;36:2341)…….88% expressed doubts about physicians’ ability to make accurate prognostications……Most respondents attributed their skepticism to the religious belief that God could intervene in any case……..Some doubted anyone’s ability to predict the future, and others cited previous experience with inaccurate medical prognoses…….Only one third of surrogates stated that specific prognostic information would play a role in their decision making, but, even so, every surrogate wanted to know the prognosis…..face-to-face discussions with surrogates may be more important than the discussion results itself.

• Patients with advanced cancer who used their religious faith to help them cope with their disease were more likely to receive intensive and aggressive treatment (mechanical ventilation or resuscitation in the last week of life) during their last week of life (JAMA. 2009;301:1140-1147)….suggest that a reliance on religion to cope with terminal cancer may contribute to aggressive medical care in the last days of life…..”Because aggressive end-of-life cancer care has been associated with poor quality of death and caregiver bereavement adjustment, intensive end-of-life care might represent a negative outcome for religious copers.”

Tips on Talking to the Family:

Link: Conteplating Withdrawal of ALS | Family Meetings | Dealing with Conflict |

Families members of critical pt’s want information in an understandable language, honest answers, specific facts about what is wrong with the pt, prognosis for recovery, want to be assured of the pt’s comfort, want to believe that hospital personnel care about the pt, want info from the physician at least qd, want to be called at home about changes in the pt’s status, they want to be comforted, to express emotions and if critical they want to find meaning in the death of their loved one. Focus on what the pt would have wanted.

If contemplating withdrawal of advanced life support: