Chapter 5 Analgesic Discography

There is currently little data to support or refute the value of analgesic disc testing and there are no published standards for evaluation.

There is currently little data to support or refute the value of analgesic disc testing and there are no published standards for evaluation. Ideally, one would perform analgesic testing as a separate procedure on one disc at a time and probably no more than two discs per session.

Ideally, one would perform analgesic testing as a separate procedure on one disc at a time and probably no more than two discs per session. The test is perhaps best used to persuade a patient or surgeon that the disc is not the source of pain.

The test is perhaps best used to persuade a patient or surgeon that the disc is not the source of pain. A negative test does not rule out other segmental pain sources, including perhaps mechanical pain secondary to outer annular strain.

A negative test does not rule out other segmental pain sources, including perhaps mechanical pain secondary to outer annular strain. Conceptually, pain relief of approximately 70% or more following local anesthetic injection would better predict outcome following intradiscal injection of a neurolytic solution.

Conceptually, pain relief of approximately 70% or more following local anesthetic injection would better predict outcome following intradiscal injection of a neurolytic solution. Requiring a positive response to local anesthetic infiltration to justify fusion or arthroplasty for internal disc disruption (IDD) would significantly reduce the number of authorized surgical cases.

Requiring a positive response to local anesthetic infiltration to justify fusion or arthroplasty for internal disc disruption (IDD) would significantly reduce the number of authorized surgical cases. The predictive use of analgesic testing may be robust or at least better than provocative testing, but only two case series studies are published. Both studies injected local anesthetic after provocative testing.

The predictive use of analgesic testing may be robust or at least better than provocative testing, but only two case series studies are published. Both studies injected local anesthetic after provocative testing. Analgesic testing should be considered in patients with low pain tolerance and abnormal psychological scores as the results of provocation testing are considerably less robust in this patient group.

Analgesic testing should be considered in patients with low pain tolerance and abnormal psychological scores as the results of provocation testing are considerably less robust in this patient group. If pain originates from nociceptors within a torn annulus, one may expect relief of pain within 30 minutes after injection of local anesthetic. On the other hand, pain due to mechanical strain on the outer annulus or posterior longitudinal ligament may not be relieved.

If pain originates from nociceptors within a torn annulus, one may expect relief of pain within 30 minutes after injection of local anesthetic. On the other hand, pain due to mechanical strain on the outer annulus or posterior longitudinal ligament may not be relieved. When a dark disc is the only pathology and one is considering percutaneous or open surgery, convincing relief of central axial pain following 1 cc of local anesthetic or less should be considered.

When a dark disc is the only pathology and one is considering percutaneous or open surgery, convincing relief of central axial pain following 1 cc of local anesthetic or less should be considered. Requiring 70% relief of pain will eliminate the disc as the primary source of pain in a majority of patients.

Requiring 70% relief of pain will eliminate the disc as the primary source of pain in a majority of patients. Injected local anesthetic will slowly diffuse through the annulus and pain relief may be delayed. Test the patient for several hours after local anesthetic disc block.

Injected local anesthetic will slowly diffuse through the annulus and pain relief may be delayed. Test the patient for several hours after local anesthetic disc block. Whereas provocational testing is prone to false-positive responses, analgesic testing is likely prone to false-negative responses.

Whereas provocational testing is prone to false-positive responses, analgesic testing is likely prone to false-negative responses. With recent published data showing toxicity of bupivacaine to cultured disc cells, consider using Xylocaine or ropivacaine.

With recent published data showing toxicity of bupivacaine to cultured disc cells, consider using Xylocaine or ropivacaine.Introduction

Only 60 years ago discs were thought to be incapable of producing pain. Much has changed in the interim—scientifically, financially, and politically. As treatment options expand and health care costs spiral, governments, insurers, providers, and patients are demanding more definitive tests to diagnose discogenic pain or, at minimum, tests that clearly lead to improved treatment outcomes. Lacking standard proof, some are again disputing the existence of discogenic pain.1–3 It is in this environment that analgesic discography (AD) and other methods for diagnosing painful disc degeneration are being actively pursued.

Absent definitive evidence, the diagnosis of discogenic pain evolved into judging a preponderance of the evidence. In some cases, history and physical examination combined with imaging findings were deemed sufficient. Unfortunately, features of the history and physical examination are unreliable,4–6 and imaging modalities cannot differentiate disc, facet joint, or sacroiliac joint mediated low back pain (LBP) from similar imaging findings in asymptomatic adults.7–12 In addition, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show multiple potential pain sources or be normal.13–15 Provocation discography (PD) was used in such cases as an aid in confirming or refuting one’s hypothesis that a particular disc was a source of a patient’s pain. The premise was simple: “If a particular disc is painful, instillation of contrast should reproduce the patient’s pain. If the disc is not the source of a patient’s pain, stressing it either should not be painful or should produce pain that is not the patient’s familiar or accustomed pain.”16

Indeed, recent analysis of all the published data on asymptomatic subjects undergoing PD shows that, if one limits pressure provocation, uses pressure-controlled manometry, and follows the standards of the International Spine Intervention Society (ISIS) and the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), the false-positive rate is less than 5% in asymptomatic volunteers without confounding factors. Even when volunteers with significant confounding factors (e.g., chronic pain, prior discectomy) are included, the false-positive rate is on average less than 10%.17 However, if one does not adhere to these strict criteria, false-positive rates are undoubtedly higher. In addition, although such guidelines are increasingly accepted, most of those performing PD still rely on manual, unrestricted pressurization and provocation of concordant pain.

Thus, although useful as one of many data points in arriving at a diagnosis, PD is not a stand-alone test. It cannot rule out other sources of pain, determine whether the disc is the primary source of pain, or determine the significance of a patient’s perceived suffering. PD can only determine if a patient’s response is statistically different from an asymptomatic volunteer with similar annular disruption experiencing the same intradiscal distending pressure. As with any subjective test, PD results can also be altered, intentionally or unintentionally, by either the discographer or the patient. An inexperienced or biased operator can produce erroneous results.1–3 Similarly, poor patient selection can increase the chance of erroneous results. Finally, the reliability of PD cannot be equated with outcome from treatment. Surgical treatment limitations do not necessarily negate the diagnostic value of discography or the diagnosis of painful internal disc disruption.

History

The first reported use of AD was in 1948 by Hirsch.18 He described diagnostic disc punctures in 16 patients with chronic LBP and negative myelograms. If disc puncture or needle movement increased the patient’s pain, he injected 0.5 mL of 1% procaine (Novocaine). “With addition of more volume into the disc, the patients experienced a temporary increase in pain, however, it resolved in 2 to 3 minutes. At 3 minutes the patient’s straight–leg raise test was negative or markedly reduced, spine mobility normalized, and spasms resolved and “the patient considered himself quite free of his lumbago.”

Subsequently, injection of local anesthetic into a presumed painful disc following PD has been used sporadically over the decades to help surgeons confirm the diagnosis of discogenic pain.4,19,20 In the late 1970s Roth19 asserted that AD more precisely confirmed both the diagnosis of discogenic pain and the pathological level compared to PD. He reported a 93% good or excellent recovery rate in 71 patients over a 2-year follow-up period using cervical AD in patients undergoing fusion.

Until recently, descriptions of AD have largely been “embedded” in the methods sections of various studies based on the preference of the discographer in attempting to select the best surgical candidates. For example, in the study by Coppes and associates14 local anesthetic was injected following PD as a confirmatory test before surgery. The authors reported that “additional injection of 0.5 to 1 mL of bupivacaine into the disc through the same needle relieved the pain for 1 to 4 hours.”4

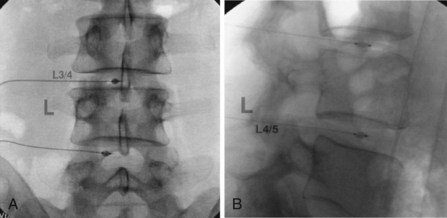

Alamin21,22 was the first to place catheters in the disc as a part of the process of AD in 2006. This allowed for multilevel anesthetic and placebo testing of the disc and for functional testing in the recovery area using common provocative lumbar range-of-motion maneuvers. Working with Kyphon-Medtronic (Sunnyvale, Calif), Alamin co-developed a balloon-tipped catheter (Discyphor) to allow for anchoring of the device in the disc during functional testing and coined the term functional analgesic discography (Fig. 5-1).

Analgesic Discography: Construct Validity

Construct validity is considered the most important type of validity, referring to the degree to which a test assesses the underlying theoretical dimensions (constructs) that are trying to be measured.23 Thus the question first arises: is the disc capable of being a pain generator? Anatomists demonstrated that the disc is indeed innervated. The normal, aging was first shown in 1981 to contain nociceptors in the outer one third of the posterior annulus and thus to be a potential pain generator.24 More recently, pathologically painful discs demonstrated neoinnervation extending to the nucleus pulposus; these discs were positive at preoperative PD testing, and they were examined histologically after removal at fusion.25 Compared to asymptomatic discs, painful internally disrupted lumbar intervertebral discs also have higher concentrations of sensory fibers in both their endplates and nucleus.4,26 This high concentration of sensory fibers combined with increased levels of proinflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL)-8 and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) are theorized to cause hyperalgesia and pain on loading.27,28 In fact, in this hyperalgesic state even normal mechanical loading, especially lateral shear and torsion, is painful.

Conversely, leakage of local anesthetic through an outer annular tear could block adjacent structures at the same or adjacent levels, including the sinuvertebral nerve that innervates the disc or the adjacent posterior longitudinal ligament, which is an integral part of the disc. Indeed, Bartynski and Rothfus29 reported that pain relief during PD correlated with leak of local anesthetic through outer annular tears. However, their study was a retrospective review without controls. Patients “were continuously asked” whether their pain subsided after moderate-to-rapid manual injection contrast followed by 2% lidocaine (Xylocaine). The time after injection was not recorded; thus one might assume that the next level was injected within 5 minutes, an insufficient time for lidocaine to diffuse through the outer annulus. Regardless of whether or not local anesthetic is injected, experience shows that pain often subsides if it was provoked by the opening of an annular tear or if pressure on the outer annulus/endplates is not maintained as a result of a leak. Their finding that patients reported complete or partial relief in only 31% of the painful discs with intact outer annulus compared to 89% of leaking discs could also be caused by false-negative responses resulting from the activation of unblocked pain receptors within the annulus, posterior annular ligament, or endplates/vertebral bodies by persisting annular tension.

Nontechnical factors can also lead to erroneous AD results. Neurophysiological phenomenon with convergence of neurons from adjacent receptor fields might lead to false-positive results. On the other hand, central sensitization or uninvestigated alternative pain sources (e.g., multiple discs, secondary muscle spasms, sacroiliac joint, zygapophyseal joint) may contribute to LBP and lead to a false-negative AD response. Even in patients in whom all other known sources of pain have been excluded, pain relief is rarely complete following AD. Although DePalma and associates30 reported that 80% of patients achieved ≥50% reduction in visual analog scale (VAS), Alamin’s,21 Alamin, Arawal, and Carragee’s,22 Derby and Lee’s,31 and Derby and associates32 patients reported considerably less pain relief. Indeed, in all of the studies of AD to date, most patients did not obtain pain relief approaching 75% to 100%. Where is the origin of the unrelieved pain? Does this pain originate from a source outside the disc or is it caused by the inherent limitations of AD? These questions remain unanswered.

Comparisons of Analgesic Discography with Provocation Discography

Although the evidence largely supports the face validity (the extent to which a test superficially appears to measure what it is supposed to measure)23 of AD, questions remain. First and foremost, without knowing the sensitivity or specificity or either AD or PD, we cannot know whether disagreement between them is caused by false-positive or false-negative results in one or the other test; that limitation notwithstanding, comparison studies of PD and AD have been published.

Alamin21,22 compared the ability of FAD and PD to predict surgical outcome in 41 patients. All patients underwent preprocedure functional testing to determine which activities were painful and rated the pain that each activity elicited. Standard PD was then performed on all patients. Before leaving the operating suite, a balloon-tipped catheter was inserted into the PD-positive discs. In the recovery room he sequentially injected the catheter(s) with normal saline followed by testing with 0.75 mL of local anesthetic (4% lidocaine or 0.75% bupivacaine). The patients then underwent repeat functional testing within 20 minutes in positions that typically provoked their pain. Alamin, Arawal, and Carragee’s 2007 NASS abstract22 reports the following: “7 of the 41 (17%) patients had two-level findings on PD that were reduced to one-level findings on the FAD test. 11 patients (27%) had positive provocation discograms that were negative on FAD testing. Two patients (5%) had a negative provocation discogram and yet pain relief on the FAD. 21 patients (51%) had confirmatory findings on the FAD test. Distress and Risk Assessment Method (DRAM) profile of distressed depressive or distressed somatic was a significant predictor of negative findings on the FAD test.”

Alamin reported a 44% false-positive PD rate per patient (27% of patients with single-level positive PD had a negative FAD, plus 17% with two-level positive PD reduced to one level with FAD), but it was not substantiated by DePalma and associates.30 Using a similar protocol, DePalma and colleagues performed PD followed by insertion of Discyphor FAD catheters into each positive disc. Data were collected on all patients but, as per ISIS criteria, he excluded patients with more than two positive levels. After a post-PD computed tomography (CT) scan, patients graded provoked pain in sitting, lumbar flexion, flexion/axial rotation, and supine positions. The disc(s) were then sequentially injected with 0.8 mL of 4% lidocaine. Confirmation of successful disc anesthetization was performed using an intradiscal saline challenge to ensure that distention did not produce pain. The patients then underwent postprocedure functional retesting over the following 5- to 10-minute period. He found a strong correlation between PD and AD, with 80% of positive PD discs demonstrating ≥50% pain reduction during FAD and an additional 8% demonstrating a 25% to 50% or partial reduction. Patients with confounding psychological factors showed the same correlation; contrary to Alamin’s findings,21 co-morbid depression or somatization was a significant predictor of results. The predictive value for surgical outcomes was not studied.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree