Innervation of the iliac crest. The course of the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves is shown. Injection sites for nerve blocks are indicated.

Subsequently, the nerves ascend to pierce the transversus abdominis muscle and travel within the transversus abdominis plane (TAP), between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. The exact location where these nerves enter the TAP is variable. However, it should be noted that the ilioinguinal nerve travels deep to the transversus abdominis muscle for a significant distance, often entering the TAP close to the anterior superior iliac spine. Within the TAP, the nerves lie deep to a fascial layer that separates them from the internal oblique muscle [2]. There is extensive neural branching and anastomoses between the nerves within the TAP. The nerves give rise to lateral cutaneous branches, which exit the TAP near the midaxillary line to innervate the anterolateral abdominal wall. Beyond the anterior axillary line, the terminal branches exit the TAP and ascend gradually to innervate the antero-medial abdominal wall and inguinal region.

Regional anesthetic techniques for iliac crest bone graft harvesting rely on block of the T12 and L1 nerves. Enumerated from proximal to distal needle-insertion sites, these include thoracolumbar paravertebral nerve block, transversalis fascia plane block, TAP block in the triangle of Petit, and TAP block in the mid axillary line.

Thoracolumbar paravertebral nerve block

A paravertebral nerve block involves placement of a local anesthetic solution in close proximity to the segmental spinal nerves as they exit the intervertebral foramen. The block targets the spinal nerves proximal to the take-off of lateral cutaneous sensory branches and the formation of their terminal nerves. A unilateral, segmental, sensory, motor, and sympathetic block results.

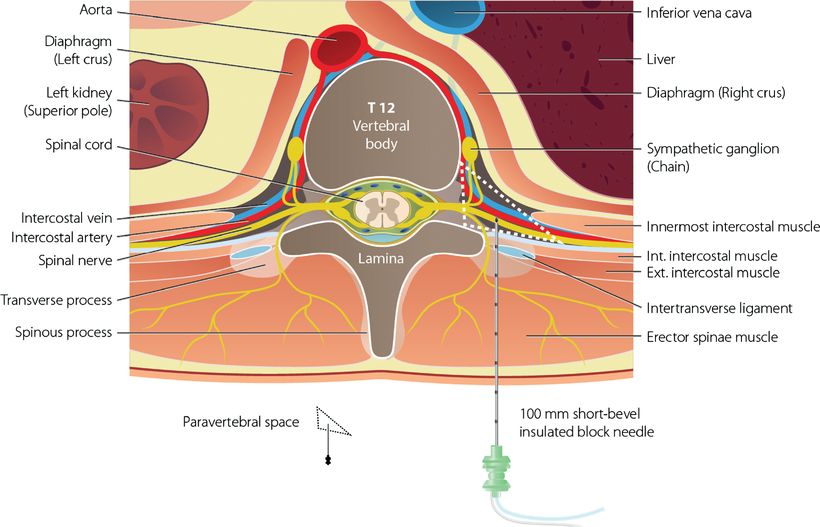

The thoracic paravertebral space at the T12 level is a wedge-shaped space located on either side of the vertebral column (Figure 34.2).

The location and contents of the T12 thoracic paravertebral space. Needle trajectory for T12 paravertebral block.

It is bounded medially by the T12 vertebral body, the intervertebral disc and foramen; and posteriorly by the intertransverse and costotransverse ligaments, rib, and transverse process. The anterior/deep boundary is formed by the diaphragm. Further anterior to this lies the liver (on the right) or the upper pole of the left kidney and spleen (on the left). The contents of the thoracic paravertebral space include the dorsal and ventral rami of the spinal nerves, the sympathetic trunk, the rami communicantes, blood vessels, and adipose tissue.

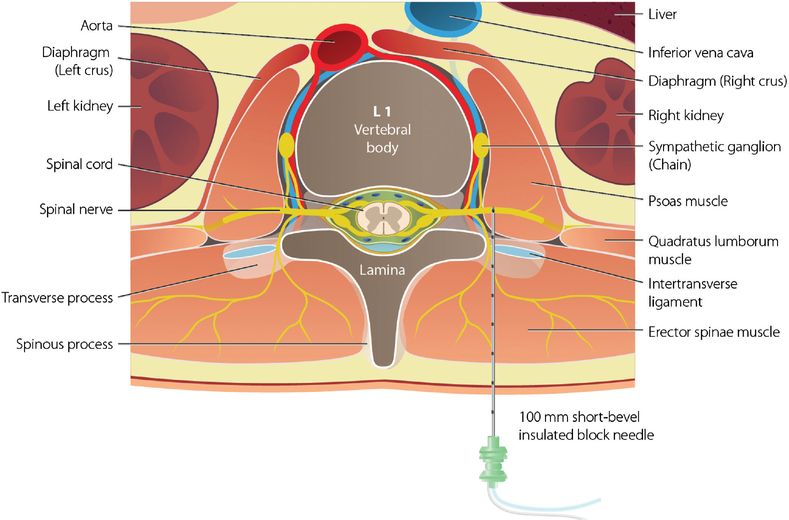

The paravertebral area at the L1 level differs significantly (Figure 34.3).

The location and contents of the L1 lumbar paravertebral space. Needle trajectory for L1 paravertebral/psoas compartment block.

The upper lumbar nerve roots do not pass through a clearly defined paravertebral space. Instead they pass through or over the posterior part of the psoas muscle, which is closely applied to the lateral aspect of the spinal column. The term “psoas compartment” is often used to describe this area. The erector spinae muscles and lumbar transverse processes form the posterior boundary of the lumbar paravertebral area.

The diaphragm and psoas muscle separate the thoracic and lumbar paravertebral areas; however, communication may occur via the medial and lateral arcuate ligaments of the diaphragm. Unpredictable cephalo-caudal spread of local anesthetic solution necessitates individual blockade of both the T12 and L1 spinal nerve roots for iliac crest analgesia.

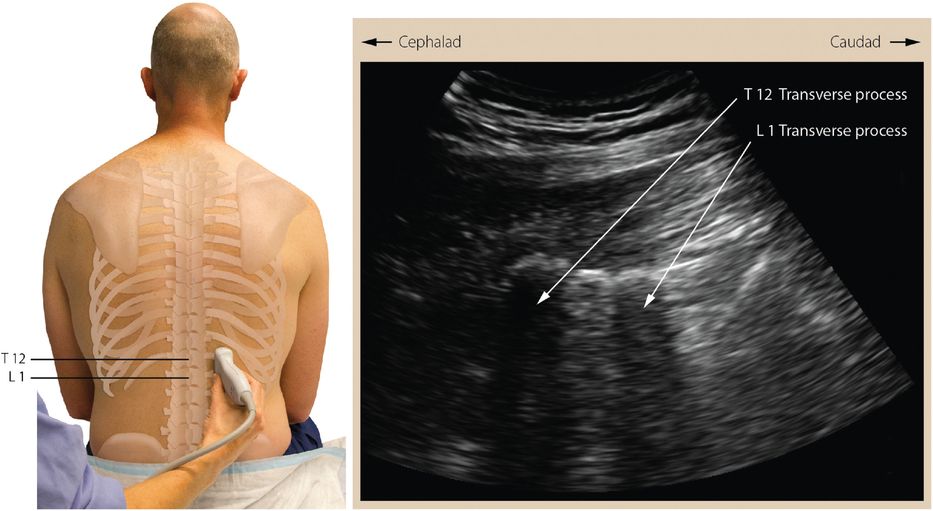

Use of a thoracolumbar paravertebral block for iliac crest analgesia has been described. It is important to note that the superior costotransverse ligament and pleura, which are the key ultrasonographic landmarks in US-guided upper and mid-thoracic paravertebral nerve blockades, are not present at the T12 and L1 levels. Furthermore, lumbar spinal nerves exist within the substance of the psoas muscle and not in a discrete paravertebral space containing adipose and connective tissue. Real-time US guidance is therefore difficult and US may be more useful for establishing the vertebral level and estimating depth to the transverse processes (Figure 34.4).

Parasagittal view showing hypoechoic transverse processes.

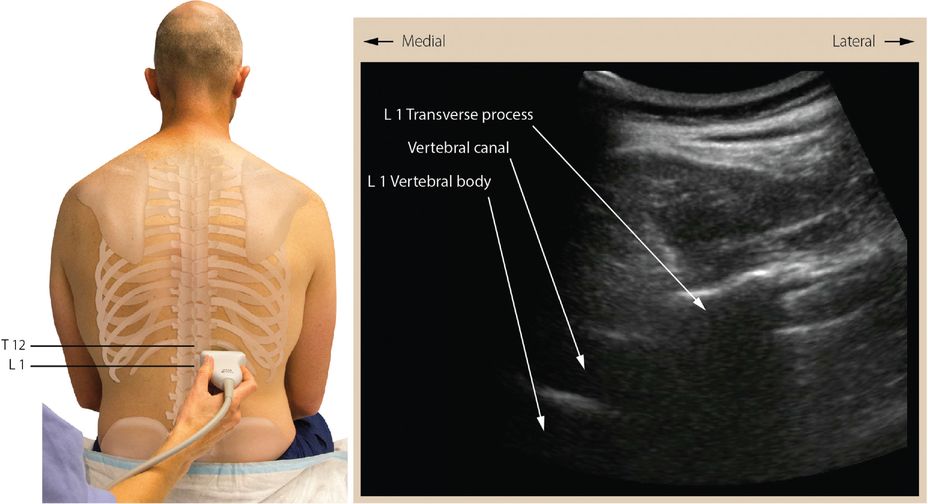

The patient is placed sitting, in the lateral decubitus or prone position. A low-frequency 3 to 5 MHz curvilinear US transducer is used to identify the L1 vertebral body as well as the depth and location of its associated transverse process (Figure 34.5). Skin markings are made in the midline over the L1 spinous process and over the L1 transverse process on the side to be blocked (approximately 2 cm from midline). Local anesthetic is injected subcutaneously at the needle-insertion site. A 100 mm short-bevel insulated block needle and nerve stimulator are used. The needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin and advanced to contact the transverse process at the expected depth based on US imaging. The actual depth to the transverse process is noted.

Oblique transverse view showing hypoechoic bony structures (vertebral body medially and transverse process laterally).

The needle is withdrawn to the skin, first redirected cranially over the L1 transverse process to block the T12 nerve root and subsequently advanced caudal to the L1 transverse process to block the L1 nerve root. The needle is advanced 0.5 to 1 cm deep to the transverse process to elicit contraction of lower intercostals, abdominal wall, or quadratus lumborum muscles. Acceptable stimulating current may be as high as 1.0 mA. Motor response may not be elicited at the L1 level despite correct needle position if local anesthetic solution injected at T12 has spread caudally to produce an L1 block. Typically 5 to 10 ml of long-acting, epinephrine-containing local anesthetic solution is administered at each of the two levels to be blocked.

Transversalis fascia plane block

The transversalis fascia plane block [3–4] is an abdominal wall block of the iliohypogastric (T12, L1) and ilioinguinal (L1) nerves. The nerves are targeted lateral to the quadratus lumborum muscle, deep to the transversus abdominus muscle, and proximal to the site at which the nerves enter the TAP. This nerve block occurs distal to the paravertebral block but proximal to the TAP block.

The transversalis fascia plane block may be performed with the patient supine or in the lateral decubitus position. A low-frequency 3 to 5 MHz curvilinear transducer is used to provide adequate resolution and field of view; however, a high-frequency linear transducer may be appropriate in slender patients. The transducer is placed in a transverse orientation just cephalad to the iliac crest at the posterior axillary line. The external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles are identified and traced posteriorly until the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles are observed to taper into a common aponeurosis (the thoracolumbar fascia) adjacent to the quadratus lumborum.

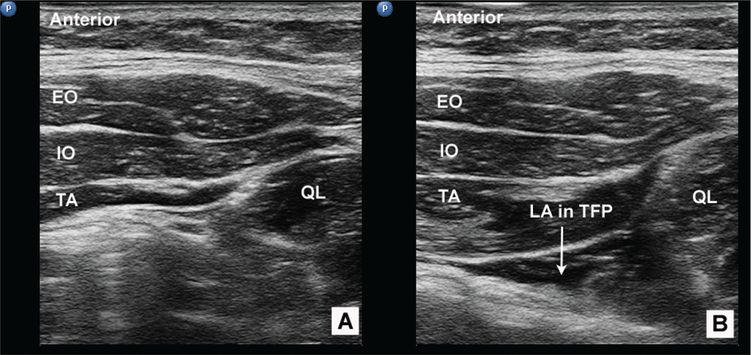

A 22G, 50 to 100 mm short-bevel block needle is inserted in-plane in an anterior-to-posterior direction until the tip is positioned just under the aponeurosis deep to the tapered tip of the transversus abdominis muscle. Hydrolocation with dextrose or saline helps confirm needle tip position during advancement. Correct location results in the local anesthetic solution spreading out along the fascial planes (Figure 34.6).

Transversalis fascial plane block: ultrasound view. (A) Ultrasound image shows the external oblique (EO), internal oblique (IO), transversus abdominis (TA), and quadratus lumborum (QL) muscles of the posterolateral abdominal wall. (B) Ultrasound image following injection demonstrates local anesthetic in the transversalis fascial plane (TFP).

If the transversus abdominis muscle is observed to distend, the needle needs to be advanced another fascial “pop” deeper. Commonly 20 ml of long-acting, epinephrine-containing local anesthetic solution is injected in small aliquots.

Transversus abdominis plane block

The TAP block involves the placement of local anesthetic solution in close proximity to the nerves that travel within the TAP. Two approaches to this block are relevant to the discussion of iliac crest analgesia – the landmark-based “triangle of Petit” and the US-guided “classic lateral” techniques. For both approaches, the patient can be in the supine or lateral decubitus position. The heterogeneity of studies on TAP blocks prevented a systematic review from recommending the ideal concentration and volume of local anesthetic for this block [5]. Commonly, 20 ml of dilute long-acting, epinephrine-containing local anesthetic solution is used.

Landmark-based “triangle of Petit” technique

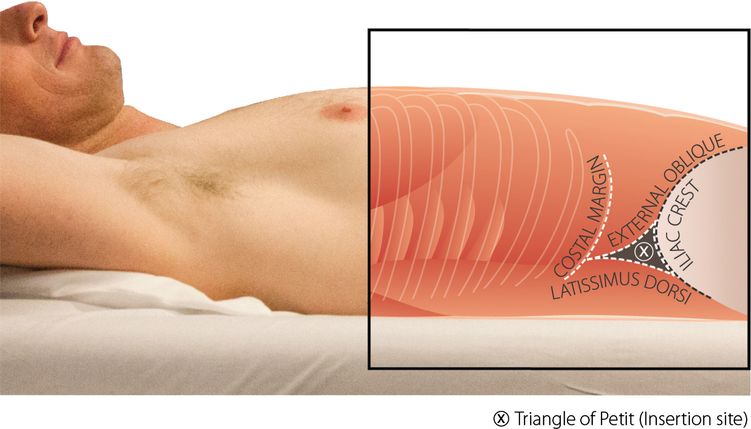

In the landmark-based technique, the TAP is accessed by the lumbar triangle of Petit [6–7]. The borders of the triangle of Petit include the latissimus dorsi muscle posteriorly, the external oblique muscle anteriorly, and the iliac crest inferiorly (Figure 34.7).

Landmarks of the triangle of Petit. The needle-insertion site for the landmark-based TAP block is the triangle of Petit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree