AN APPROACH TO THE UNCONSCIOUS VICTIM

Any disorder that decreases the supply of oxygen or sugar to the brain or that causes brain swelling, bleeding into the brain, or alteration of critical body chemistries can lead to unconsciousness. Thus, virtually every major illness or injury can ultimately render a person unconscious. If you come across someone who cannot be awakened, you must rapidly assess him for any treatable life-threatening conditions, and then try to discover the cause of the altered mental state.

1. Evaluate the airway (see page 22).

2. Evaluate breathing (see page 28).

3. Check for pulses (see page 33).

4. Protect the cervical spine (see page 37).

5. Control obvious bleeding (see page 53).

6. Examine the victim for chest injury (see page 42), broken bones (see page 70), and burns (see page 108).

7. Consider shock (see page 60), head injury (see page 61), seizure (see page 68), severe allergic reaction (see page 66), low blood sugar (see page 142), stroke (see page 144), fainting spell (see page 165), hypothermia (see page 305), heat illness (see page 322), high-altitude cerebral edema (see page 340), high-altitude pulmonary edema (see page 339), lightning strike (see page 395), poisoning, and alcohol (drug) intoxication.

8. Remove contact lenses (see page 183).

9. Transport the victim to medical attention (see page 459).

HELMET REMOVAL

1. The first rescuer, positioned above the head of the victim, holds the helmeted head steady by grasping it on each side. If necessary to support the airway, the first rescuer can reach down and hold the mandible (lower jaw).

2. The second rescuer, positioned below the head of the victim, prepares the helmet for removal by loosening and removing straps, goggles, and other attachments, so long as this process does not allow for unintended head movement.

3. The second rescuer takes over head stabilization, while the first rescuer continues to hold the helmeted head, by sliding two hands along the sides of the victim’s head position; this should be done by either placing one hand behind the base of the head at its junction with the neck and the other hand under the chin or by sliding two hands along the sides of the head and up inside the helmet.

4. The first rescuer completes removal of retaining straps, then slides the helmet off the head using axial (straight up away from the feet, without any twisting) traction.

5. Head positioning and gentle traction is maintained while a cervical collar or other method (see page 37) is used to stabilize the position of the head and neck.

AIRWAY

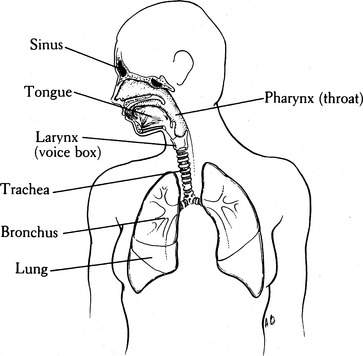

Figure 2 depicts the anatomy of the respiratory system. Air enters the mouth and nose (where it is humidified), traverses the pharynx (throat), passes through the trachea (windpipe) and bronchi, and normally proceeds into the smallest air sacs of the lungs, known as the alveoli. Within these distal air spaces, inspired oxygen is exchanged for carbon dioxide, one of the end products of human metabolism. During swallowing, the epiglottis and tongue cover the entrance (via the vocal cords) to the trachea, so that food and liquid enter the esophagus and not the airway.

Symptoms of airway obstruction include sudden inability to speak, an appearance of panic with bulging eyes, blue skin discoloration (cyanosis), choking gestures (hand held to the throat) (see Figure 11), harsh and raspy or “musical” and high-pitched noise (“stridor”) that comes from the throat during breathing, and difficulty with breathing as evidenced by struggling and profound agitation. Any person who collapses suddenly, particularly while eating, or who has been in an accident should be examined rapidly for airway obstruction.

1. Under no circumstance should the neck be manipulated if there is a possibility of injury to the spine or spinal cord. If a victim is unconscious and has suffered a fall or multiple injuries, it is safest to assume that his neck is broken. If this is the case, keep the airway open by gently but firmly lifting the jaw, either by grasping the lower teeth and jaw and pulling directly forward (away from the face), or by maintaining a forward pull on the angles of the jaw (Figure 3). Do not bend the neck forward or backward. A modified jaw thrust (Figure 4) can be performed by a single rescuer while stabilizing the neck.

2. If there is no chance of a broken neck, maintain the airway with the jaw lifts previously described or by tilting the head backward while gently lifting under the neck (Figure 5). The alignment is different for an infant, a small child, and an older child or adult in terms of where one would position a pad or pillow (Figure 6). A head tilt with chin lift may be used (Figure 7).

3. Keep the airway clear of blood, vomitus, loose dentures, and debris. This can be accomplished by sweeping the mouth with two fingers or by continuous suction with a field suction apparatus powerful enough to extract chunks. Take care not to force objects deeper into the throat. If the tongue appears to be the problem, wrap the end of the tongue in a cloth or gauze bandage, grasp firmly, and pull it out of the mouth (Figure 8). If it cannot be held in this manner, a large safety pin or sharp-pointed wire may be passed through the tongue and used to improve the grip (see Figure 8); take care to avoid the large, visible blood vessels at the base of the tongue. To keep the tongue out of the mouth, a string can be tied to the safety pin and then secured to the victim’s shirt button or jacket zipper. Fortunately, in most cases the jaw lift will carry the base of the tongue out of the airway. Another technique is to use two safety pins to attach the tongue to the face just below the lower lip (Figure 9).

4. If the victim is unconscious, and there is no chance of a broken neck or back, do not leave him lying flat on his back. Turn him on his side so that if vomiting occurs, the fluid can drain from his mouth and the victim won’t choke or drown (Figure 10).

5. Choking is a life-threatening condition in which the upper airway (above the vocal cords) is obstructed by a foreign object (tongue, broken teeth, dentures, food). The choking person is profoundly agitated (until he becomes unconscious from lack of oxygen), may appear to be panicked with bulging eyes, may grasp at his throat in a choking gesture, cannot breathe, and is unable to speak. You must respond rapidly:

6. If necessary, begin mouth-to-mouth breathing (see page 29).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree