The evaluation of amenorrhea in the adolescent requires a basic understanding of pubertal development, including the role of the hypothalamic-pituatary-ovarian (HPO) axis and its effect on the menstrual cycle. The differential diagnosis for primary and secondary amenorrhea are very similar except for a few genetic conditions that only cause primary amenorrhea.

Both primary and secondary amenorrhea can be assessed in a similar manner. Begin with a complete history and physical examination, followed by a step-by-step laboratory evaluation. If a methodical approach is utilized, the pediatrician can diagnose and manage most cases of amenorrhea. The practitioner should be sensitive to the effect amenorrhea can have on an adolescent’s body image and sexual identity.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

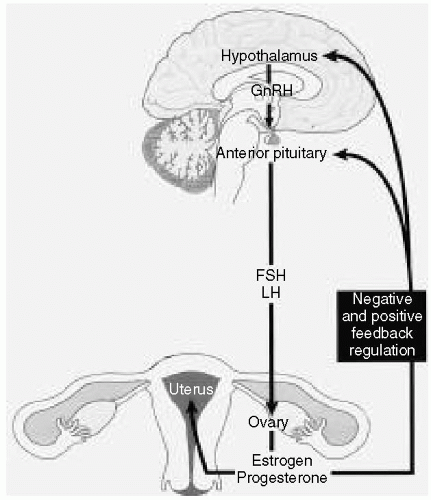

The HPO axis is directly responsible for regulating the menstrual cycle

(Fig. 46.1). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus stimulates the release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary. FSH and LH influence the ovarian production of estrogen and progesterone, which in turn have both a positive and negative feedback effect on the pituitary and the hypothalamus.

PHASES OF THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

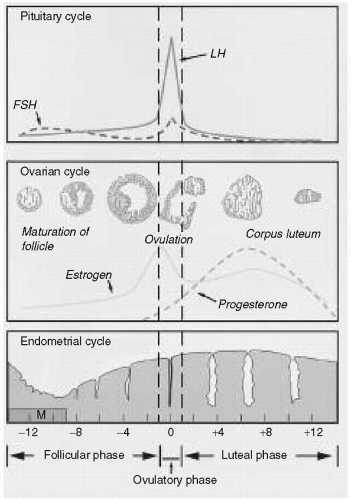

The menstrual cycle can be broken down into three phases

(Fig. 46.2).

Follicular Phase

During the menses, low ovarian levels of estrogen stimulate the production of FSH. Final maturation of the follicle occurs under the stimulation of FSH. As the ovarian production of estrogen increases, the rising estrogen levels have a negative effect on FSH and a positive effect on LH. During the second half of this phase, estrogen stimulates growth of the endometrium.

Ovulatory Phase

The surge in LH secondary to positive estrogen feedback results in ovulation. As LH levels peak, estrogen levels fall.

Luteal Phase

This phase corresponds to the lifespan of the corpus luteum, which secretes progesterone and estrogen. Under the influence of these hormones, the endometrium becomes thicker and more vascular. Plasma levels of LH and FSH decline. If fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum involutes within 14 days and estrogen and progesterone levels fall. With a fall in the levels of these hormones, the endometrium becomes necrotic and sloughs off in the process known as menstruation.

MENARCHE AND THE ADOLESCENT MENSTRUAL CYCLE

Menarche occurs at a mean age of 12.5 years, with a range of 9 to 16 years. In most cases it occurs 1 year after the peak growth velocity and 2 years after the development of breast buds. By menarche, most girls have completed 75% of their pubertal development and achieved 90% of their growth potential. Early menstrual cycles are anovulatory. Ovulation usually begins within 1 to 2 years after menarche and reflects synchronization and maturation of the HPO axis. A normal menstrual period lasts from 2 to 7 days, with an average blood loss between 30 and 40 mL. Cycle lengths can vary between 21 to 45 days but are usually constant for a given individual.

ETIOLOGY OF AMENORRHEA

In considering the etiology of amenorrhea (

Table 46.1), it is helpful to think about where along the HPO axis the problem exists. Try to differentiate a central problem at the level of the hypothalamus or pituitary from an ovarian problem or an end-organ problem. The classification of

hypogonadotropic hypogonadism refers to low FSH and LH levels seen in conditions affecting the hypothalmus and the pituatary.

Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism refers to to high FSH and LH levels seen in conditions affecting the ovary. In

eugonadotropic conditions FSH and LH levels are normal.

Hypothalamic Disorders

Any condition associated with a deficiency of GnRH can cause amenorrhea. Constitutional delay of puberty is a common etiology of primary amenorrhea. This condition may be associated with short stature and a family history of delayed puberty or delayed menarche in an older sibling or parent. Other conditions that cause GnRH deficiency include hypothalamic tumors, isolated GnRH insufficiency, and Kallmann syndrome (GnRH deficiency and anosmia). Any type of chronic disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and diabetes; nutritional problems (e.g., anorexia, bulimia, obesity), rigorous exercise, stress, and substance abuse can also result in GnRH deficiency.

Pituitary Disorders

Pituitary disorders that can cause amenorrhea include tumors such as prolactinomas and craniopharyngiomas. Other causes are idiopathic hypopituitarism and a history of central nervous system infection.

Ovarian Disorders

Turner syndrome is one of the most common chromosomal disorders in humans and one of the most frequent causes of primary amenorrhea. It is characterized by a 45,XO karyotype, although up to 50% of affected persons may exhibit mosaicism (46,XX/45,XO). Some of the stigmata of Turner syndrome include short stature, webbed neck, shield chest, and streak ovaries.

Female gonadal dysgenesis is characterized by a 46,XX karyotype and streak ovaries.

Gonadal dysgenesis with a variety of other abnormal karyotypes such as XY or XXY may also occur. They are a rare cause of amenorrhea. Other ovarian conditions that result in amenorrhea include polycystic ovary syndrome and ovarian failure secondary to infection, radiation, chemotherapy, autoimmune disease, or an idiopathic cause.

Structural or End-organ Defects

Any sort of genital tract obstruction can result in amenorrhea. An imperforate hymen or a transverse vaginal septum will often present with cyclic pain resulting from the accumualtion of blood behind the obstruction. Asherman syndrome is iatrogenic scarring of the uterine lining, usually secondary to trauma sustained during a dilation and curettage procedure or infection. Mullerian agenesis refers to partial or complete agenesis of the vagina. The uterus and fallopian tubes are usually absent or rudimentary and the karyotype is 46,XX. In complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, the individual appears phenotypically female with normal female breasts and external genitalia. However, the vagina ends in a blind pouch and pubic hair is absent or sparse. The karyotye is 46,XY and inguinal or intra-abdominal testes are present. Because of the risk of malignancy, the testes should be removed after breast development and adult stature have been achieved.

Other Causes

Pregnancy should always be considered in both primary and secondary amenorrhea. Other considerations include hormonal contraception and endocrinopathies such as diabetes, thyroid disease, and adrenal disease.