Airway Evaluation and Management

David G. Frazer

Ulrich Schmidt

I. APPLIED ANATOMY

A. The pharynx is divided into the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx.

1. The nasopharynx consists of the nasal passages, including the septum, turbinates, and adenoids.

2. The oropharynx consists of the oral cavity, including the dentition and tongue.

3. The epiglottis separates the laryngopharynx into the larynx (leading to the trachea) and the hypopharynx (leading to the esophagus).

B. The Larynx

1. The larynx, located at the level of the fourth to the sixth cervical vertebrae, originates at the laryngeal inlet and ends at the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage. It consists of nine cartilages; three unpaired (thyroid, cricoid, and epiglottis) and three paired (corniculates, cuneiforms, and arytenoids); ligaments; and muscles.

2. The cricoid cartilage, located just inferior to the thyroid cartilage at the C5-6 vertebral level, is the only complete cartilaginous ring in the respiratory tree.

3. The cricothyroid membrane connects the thyroid and cricoid cartilages and measures 0.9 × 3.0 cm in adults. The membrane is superficial, thin, and devoid of major vessels in the midline, making it an important site for emergent surgical airway access (see Cricothyroidotomy below).

4. The laryngeal muscles can be divided into two groups: muscles that open and close the glottis (lateral cricoarytenoid [adduction], posterior cricoarytenoid [abduction], and transverse arytenoid) and muscles that control the tension of the vocal ligaments (cricothyroid, vocalis, and thyroarytenoid).

5. Innervation

a. Sensory. The glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX) provides sensory innervation to the posterior one third of the tongue, the oropharynx from its junction with the nasopharynx, including the pharyngeal surfaces of the soft palate, epiglottis, and the fauces, to the junction of the pharynx and esophagus. The internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, a branch of the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), provides sensory innervation to the mucosa from the epiglottis to and including the vocal cords. The sensory fibers of the inferior laryngeal nerve, a branch of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (also a branch of the vagus nerve), provides sensory innervation to the mucosa of the subglottic larynx and trachea.

b. Motor. The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve provides motor innervation to the cricothyroid muscle. Activation of this muscle results in tensing of the vocal cords. The motor fibers of the inferior laryngeal nerve provide motor innervation to all other intrinsic muscles of the larynx. Bilateral injury to the inferior laryngeal

nerves (e.g., via injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerves) can produce unopposed activation of the cricothyroideus, leading to tensing of the vocal cords and airway closure.

nerves (e.g., via injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerves) can produce unopposed activation of the cricothyroideus, leading to tensing of the vocal cords and airway closure.

C. The glottis is composed of the vocal folds (true and “false” cords) and the rima glottidis.

1. The rima glottidis describes the aperture between the true vocal cords.

2. The glottis represents the narrowest point in the adult airway (more than 8 years of age), whereas the cricoid cartilage represents the narrowest point in the infant airway (birth to 1 year of age).

D. The lower airway extends from the subglottic larynx to the bronchi.

1. The subglottic larynx extends from the vocal folds to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage (C6).

2. The trachea is a fibromuscular tube that is 10 to 12 cm long with a diameter of approximately 20 mm in adults. It extends from the cricoid cartilage to the carina. The trachea is supported by 16 to 20 U-shaped cartilages, with the open end facing posteriorly. Noting the posterior absence of cartilaginous rings provides anterior-posterior orientation during fiberoptic exam of the tracheobronchial tree.

3. The trachea bifurcates into the right and left main stem bronchi at the carina. The right main stem bronchus is approximately 2.5 cm long with a takeoff angle of approximately 25 degrees. The left main stem bronchus is approximately 5 cm long with a takeoff angle of approximately 45 degrees.

II. EVALUATION

A. History. A history of difficult airway management in the past may be the best predictor of a challenging airway. If old medical records are available, prior anesthetic records should be reviewed for the ease of intubation and ventilation (the ability to mask ventilate, and whether adjuncts to mask ventilation were required; the number of intubation attempts; the type of laryngoscope blade used; the size of the endotracheal tube (ETT); or if any specialty airway equipment, i.e., video laryngoscopy or a fiberoptic scope were required). Particular importance should also be placed on diseases that may affect the airway. Specific symptoms related to airway compromise should be sought, including hoarseness, stridor, wheezing, dysphagia, dyspnea, and positional airway obstruction.

1. Arthritis or cervical disk disease may decrease neck mobility. Cervical spine instability and limitation of mandibular motion are common in rheumatoid arthritis. The temporomandibular and cricoarytenoid joints may also be involved. Aggressive neck manipulation in these patients may lead to atlantoaxial subluxation and spinal cord injury. The risk of atlantoaxial subluxation is highest in patients with severe hand deformities and skin nodules.

2. Infections of the floor of the mouth, salivary glands, tonsils, or pharynx may cause pain, edema, and trismus with limited mouth opening.

3. Tumors may obstruct the airway or cause extrinsic compression and tracheal deviation.

4. Increased body mass index (BMI) is often a challenge during the induction of anesthesia. The increased BMI coupled with other anatomical findings (Mallampati score, increased neck circumference, short thyromental distance) can be predictive for difficult ventilation by mask and a high probability for a difficult tracheal intubation. The decreased functional residual capacity (FRC) associated with an increased in BMI can result in a precipitous desaturation with the apnea of induction.

5. Trauma may be associated with airway injuries, cervical spine injury, basilar skull fracture, or intracranial injury.

6. Previous surgery, radiation, or burns may produce scarring, contractures, and limited tissue mobility and narrow the oral aperature.

7. Acromegaly may cause mandibular hypertrophy and overgrowth and enlargement of the tongue and epiglottis. The glottic opening may be narrowed because of enlargement of the vocal cords.

8. Scleroderma may produce skin tightness and decrease mandibular motion and narrow the oral aperture.

9. Trisomy 21 patients may have atlantoaxial instability and macroglossia.

10. Dwarfism and achondroplasia patients may be associated with atlantoaxial instability and potentially difficult airway management because of mandibular hypoplasia (micrognathia).

11. Other congenital anomalies may complicate airway management, particularly pediatric and adult patients with craniofacial abnormalities such as Pierre Robin, Treacher Collins, Klippel-Feil, and Goldenhar syndromes. In contrast, children with isolated cleft palates are not specifically difficult to intubate if the condition is not associated with other airway or craniofacial abnormalities, but nasotracheal intubation should be avoided.

B. Physical Examination

1. Specific findings that may indicate a difficult airway include the following:

a. Inability to open the mouth

b. Poor cervical spine mobility

c. Receding chin (micrognathia)

d. Large tongue (macroglossia)

e. Prominent incisors

f. Short muscular neck

2. Injuries to the face, neck, or chest must be evaluated to assess their contribution to airway compromise.

3. Head and neck examination. There is no single best predictor of difficult airway management on the physical exam, so a detailed exam is in order. Multiple predictors of difficult airway will increase the specificity of the exam.

a. Nose. The patency of the nares or the presence of a deviated septum should be determined by occluding one nostril at a time and assessing ease of ventilation through the other nostril. This is especially important should nasotracheal intubation be required.

b. Mouth. Identify macroglossia and conditions that reduce mouth opening (e.g., facial scars or contractures, scleroderma, and temporomandibular joint disease). Poor dentition may increase the risk of tooth injury or avulsion during airway manipulation. Loose teeth should be identified preoperatively and protected or removed before initiation of airway management.

c. Neck

1. If the thyromental distance (the distance from the lower border of the mandible to the thyroid notch with the neck fully extended) is less than 6 cm (three to four finger breadths), there may be difficulty visualizing the glottis. The mobility of laryngeal structures should be assessed, and the trachea should be palpable in the midline above the sternal notch. Look for scars from previous neck surgery, an enlarged thyroid, other paratracheal masses, and indurated tissues suggestive of radiation therapy.

2. Cervical spine mobility. Patients should be able to touch their chin to their chest and extend their neck posteriorly. Lateral rotation should not produce pain or paresthesia.

3. The presence of a healed or patent tracheostomy stoma may be a clue to subglottic stenosis or prior complications with airway management. Smaller diameter ETTs should be available for these patients.

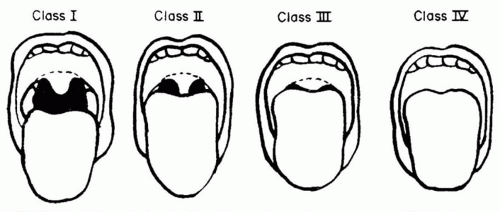

4. The Mallampati classification to predict difficult intubation is based on the finding that visualization of the glottis is impaired when the base of the tongue is disproportionately large. Assessment is made with the patient sitting upright, with the head in the neutral position, the mouth open as wide as possible, and the tongue protruded maximally without phonation. The modified classification includes the following four categories (Fig. 14.1):

a. Class I. Faucial pillars, soft palate, and uvula are visible.

b. Class II. Faucial pillars and soft palate may be seen, but the uvula is masked by the base of the tongue.

c. Class III. Only soft palate is visible. Intubation is predicted to be difficult.

d. Class IV. Soft palate is not visible. Intubation is predicted to be difficult.

C. Special Studies. In most patients, a careful history and physical examination will be all that are needed to evaluate an airway. Useful adjuncts may include the following:

1. Laryngoscopy (direct, indirect, video, or flexible fiberoptic) will provide information about the hypopharynx, laryngeal inlet, and vocal cord function. It can be performed in a conscious patient with topical anesthesia or nerve blocks.

2. Chest or cervical imaging may reveal tracheal deviation or narrowing and bony deformities in the neck. Cervical spine films are particularly important in trauma cases and should be performed in case of an injury above the clavicle or serious multiple traumatic injuries. In patients with altered mental status or distracting injuries, a normal cervical radiograph cannot rule out a significant ligamentous injury. Cervical spine precautions should be applied during intubation and computed

tomography (CT) or MRI scans should be obtained, depending on local protocols. Lateral cervical spine films may be useful in symptomatic patients with rheumatoid arthritis or Down syndrome to assess for atlantoaxial subluxation.

tomography (CT) or MRI scans should be obtained, depending on local protocols. Lateral cervical spine films may be useful in symptomatic patients with rheumatoid arthritis or Down syndrome to assess for atlantoaxial subluxation.

3. Tracheal tomograms or CT scan can delineate masses obstructing the airway.

4. Pulmonary function tests and flow volume loops can help determine the degree and site of airway obstruction (see Chapters 1 and 3).

5. Baseline arterial blood gas tensions can indicate the functional consequences of airway abnormalities and alert the clinician to patients who are chronically hypoxemic or hypercarbic.

III. MASK AIRWAY

A. Indications

1. To preoxygenate (denitrogenate) a patient before endotracheal intubation

2. To assist or control ventilation as part of initial resuscitation before an ETT is placed

3. To provide inhalation anesthesia in patients not at risk for regurgitation of gastric contents

B. Technique involves placing a face mask and maintaining a patent airway.

1. The mask should fit snugly around the bridge of the nose, cheeks, and mouth. Clear plastic masks allow for observation of the lips (for color) and mouth (for secretions or vomitus).

2. Mask placement. The mask is held in the left hand so that the little finger is at the angle of the mandible, the third and fourth fingers are along the mandible, and the index finger and thumb are placed on the mask in the shape of the letter “C.” The right hand is available to control the reservoir bag. Two hands may be required to maintain a good mask fit, necessitating an assistant to control the bag. Head straps may be used to assist mask fit. Peak inspiratory pressures should be kept below 20 cm H2O in order to minimize gastric insufflation. There are certain airway environments that may require a reversal of the handedness of mask ventilation described above, where the mask will be held in the right hand, and the left hand will control the reservoir bag. This should become an ambidextrous skill.

3. Edentulous patients may present a problem when attempting to achieve an adequate seal with the face mask because of decreased distance between the mandible and the maxilla. An oral airway will often correct this problem, and the cheeks may be compressed against the mask to decrease leaks. Two hands may be required to do this. Alternatively, dentures may be left in place during mask ventilation, but have often been removed prior to induction.

4. Airway obstruction during spontaneous ventilation may be recognized by a paradoxical “rocking” motion of the chest and abdomen. During spontaneous ventilation, if the upper airway is obstructed as the diaphragm contracts, the abdomen distends as it normally does for each breath, but the thorax collapses instead of being insufflated. Stridor is a high-pitched noise associated with an extreme narrowing of an upper airway and may be caused by diseases such as croup but is most commonly observed with laryngospasm after extubation. With airway obstruction, respiratory excursions in the reservoir bag will be decreased or absent, and peak airway pressures will be increased when positive-pressure ventilation is attempted.

5. Airway patency may be restored by the following:

a. Neck extension.

b. Jaw thrust, by placing the fingers under the angles of the mandible and lifting forward.

c. Turning the head to one side.

d. Insertion of an oral airway. An airway may not be well tolerated if the gag reflex is intact. Complications from the use of oral airways include vomiting, laryngospasm, and dental trauma. The wrong-size oral airway may worsen obstruction. If the oral airway is too short, it may compress the tongue; if it is too long, it may lie against the epiglottis.

e. A nasal airway helps maintain upper airway patency in a patient with minimal-to-moderate obstruction and is reasonably tolerated by awake or sedated patients. Nasal airways can cause epistaxis and should be avoided in patients who are anticoagulated.

C. Difficult mask ventilation may be anticipated in patients who have the following: obesity, edentition, beards, cervical arthritis, or obstructive sleep apnea. Appropriate oral and nasal airways and laryngeal mask airways (LMAs) should be available.

D. Complications. The mask may cause pressure injuries to soft tissues around the mouth, mandible, eyes, or nose. Loss of the airway may result from laryngospasm or vomiting. Mask ventilation does not protect the airway from aspiration of gastric contents. Laryngospasm, a tonic contraction of the laryngeal and pharyngeal muscles, causes airway obstruction and closure of the vocal cords that may be relieved by jaw thrust and the application of constant positive airway pressure. If this fails, a small dose of succinylcholine (20 mg intravenously or intramuscularly in the adult) may be required.

IV. LARYNGEAL MASK AIRWAY

A. The classic LMA and its multiple variations are disposable supraglottic airway management devices that can be used as an alternative to both mask ventilation and endotracheal intubation in appropriate patients. The LMA also plays an important role in the management of the difficult airway. When inserted appropriately, the LMA lies with its tip resting over the upper esophageal sphincter, cuff sides lying over the pyriform fossae, and cuff upper border resting against the base of the tongue. Such positioning allows for effective ventilation with minimal inflation of the stomach.

1. Indications

a. As an alternative to mask ventilation or endotracheal intubation for airway management. The LMA is not a replacement for endotracheal intubation when endotracheal intubation is indicated.

b. In the management of a known or unexpected difficult airway.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree