Airway, Breathing, Circulation

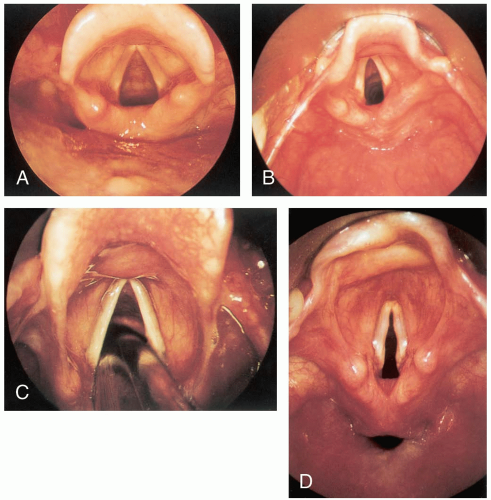

1-1 Normal Airway

Arun Nagdev

Anatomically, the upper airway begins at the nares and continues to the proximal aspect of the trachea.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with an intact and patent upper airway should show no difficulty in breathing.

Pathophysiology

Functions of the upper airway include acting as a conduit for oxygenation and ventilation, phonation, and prevention of gastric aspiration.1 Impediment of flow in the upper airway can result in stridor, agitation, hypoxia, or complete loss of upper airway sounds and flow.1 Obstruction of air flow can occur at any location along the upper airway, commonly including oropharyngeal obstruction secondary to decreased tone of the genioglossus muscle, posterior nasopharyngeal obstruction by hypertrophied lymphoid tissue, and hypopharyngeal obstruction due to inflammatory epiglottitis.1,2

Diagnosis

Clinicians must be able to detect alterations in normal upper airway anatomy or function clinically. Ancillary testing, such as lateral soft tissue neck radiographs or direct or fiberoptic laryngoscopy, may aid in determining alterations in airway anatomy.

Clinical Complications

Patients who are unable to maintain a normal airway can develop pulmonary aspiration, sepsis, hypoxia, and eventually death if airway alteration is allowed to progress uncorrected.

Management

REFERENCES

1. Issacs RS, Sykes JM. Anatomy and physiology of the upper airway. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 2002;20:733-745.

2. Morris IR. Functional anatomy of the upper airway. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1988;6:639-669.

3. Behringer EC. Approaches to managing the upper airway. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 2002;20:813-832.

1-2 Difficult Airway

Arun Nagdev

Difficult intubation is defined as inability to place an endotracheal tube (ET) after three attempts or after 10 minutes via conventional laryngoscopy.1 Difficulty in mask ventilation is defined as an inability to maintain oxygen saturation greater than 90% using 100% facemask ventilation.1

Clinical Presentation

Between 1% and 2% of intubations in the emergency department (ED) become “difficult airways.”2 Facial or neck trauma, oral swelling, morbid obesity, and abnormal facies are common causes of the difficult airway.3

Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Although many factors can alert the physician that intubation will be difficult, it is not until the procedure is actually started and difficulty is encountered that the diagnosis is realized.

Clinical Complications

Management

The operator must be experienced in alternative airway techniques in the event of a failed intubation. These “rescue techniques” include the laryngeal mask airway (LMA) and the newer intubating laryngeal mask airway (ILMA), fiberoptic-guided nasal intubation, the Combitube, and the lighted stylet.1,2,3

REFERENCES

1. Orebaugh SL. Difficult airway management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2002;22:31-48.

2. Levitan RM, Kush S, Hollander JE. Devices for difficult airway management in academic emergency departments: results of a national survey. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:694-698.

3. Butler KH, Clyne B. Management of the difficult airway: alternative airway techniques and adjuncts. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2003;21:259-289.

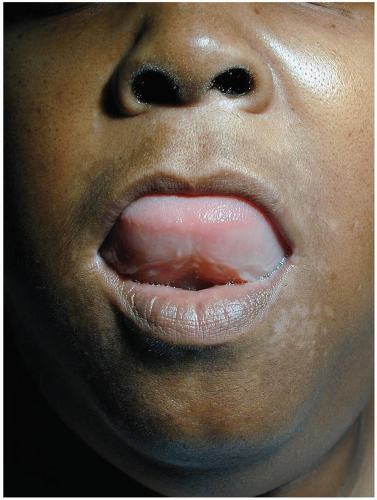

1-3 ACE Inhibitor-Associated Angioedema

Arun Nagdev

Angioedema involves extravasation of fluid into the interstitial tissues secondary to the action of inflammatory mediators leading to leakage of the capillary beds.1

Clinical Presentation

Patients have acute swelling, usually in the head and neck region and frequently involving the mouth, tongue, pharynx, and larynx.1 In severe cases involving the upper airway, stridor may be present.

Pathophysiology

The primary therapeutic objective of the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors is to decrease blood pressure (BP) by preventing the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor. However, ACE inhibitors also cause bradykinin to accumulate, which leads to increased capillary permeability. This results in the formation of interstitial edema within certain tissues. Unlike edema due to increased vascular pressures, the swelling caused by angioedema is usually rapid in onset, asymmetric in distribution, nonpitting, and not confined to dependent areas. ACE inhibitors have been implicated as the cause in 0.1% to 7.9% of angioedema cases.2 ACE inhibitor-associated angioedema is hypothesized to be caused by a bradykinin-dependent increase in vascular permeability.1

Diagnosis

Angioedema is a clinical diagnosis. If the patient presents with the characteristic swelling of the mouth, lips, tongue, or pharynx and is also taking an ACE inhibitor, the diagnosis should be highly suspected.2

Clinical Complication

Airway compromise secondary to swelling of the tongue, uvula, soft palate, and larynx is a common and potentially life-threatening complication of ACE inhibitor-associated angioedema.2

Management

Patients with impending airway compromise require the immediate establishment of a definitive airway. Those with less severe findings need early medical management with intravenous (IV) antihistamines, steroids, and subcutaneous epinephrine.2 After discontinuation of the ACE inhibitor and administration of the appropriate medications, most cases of ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema resolve within 12 to 48 hours.2 However, this angioedema can proceed rapidly to life-threatening airway closure and must be treated as a serious emergency.

REFERENCES

1. Israili ZH, Hall WD. Cough and angioneurotic edema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy: a review of the literature and pathophysiology. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:234-242.

2. Vleeming W, van Amsterdam JG, Stricker BH, de Wildt DJ. ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf 1998;18:171-188.

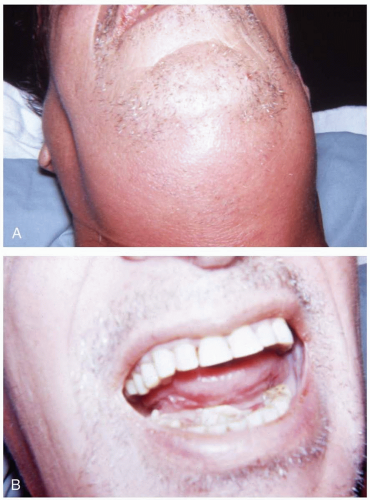

1-4 Ludwig’s Angina

Arun Nagdev

Ludwig’s angina is cellulitis originating in the submandibular space of the mouth.1

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms include sore throat, dysphonia, dysphagia, submandibular swelling, and halitosis.

Pathophysiology

Extraction or infection of teeth allows oral flora to enter the submandibular space.1 Organisms isolated from these infections include Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species in addition to anaerobes. Edema and abscess formation in the tissues below the tongue result in swelling and encroachment on the airway, eventually leading to respiratory compromise.1

Diagnosis

Patients are often febrile and dehydrated from decreased oral intake. Locally, the floor of the mouth appears “full” or swollen, and the tongue may be elevated. The submandibular region is usually tender. The floor of the mouth may appear even with the level of the teeth and may be tense to tongue blade application. In patients with no signs of airway compromise, soft tissue films of the neck may demonstrate widening or gas within soft tissue spaces. Trismus and drooling may be seen.1

Clinical Complications

Ludwig’s angina can spread through the fascial planes of the oral cavity into the neck and chest. This can lead to retropharyngeal and mediastinal infections in addition to pericardial and pleural effusions.2 If the involved tissues continue to expand, complete airway occlusion and death may result.

Management

Airway management is a clear priority. Fiberoptic-guided nasotracheal intubation is the preferred method for obtaining a definitive airway, because soft tissue swelling makes laryngoscopic intubation difficult.2 Stable patients should be kept sitting upright in a comfortable position with intubation equipment at bedside. Antibiotics—penicillin G with metronidazole, ampicillin-sulbactam, or, in penicillin-allergic patients, clindamycin—must be started in the emergency department.2 Corticosteroid therapy is controversial.3

REFERENCES

1. Moreland LW, Corey J, McKenzie R. Ludwig’s angina: report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 1988;148:461-466.

2. Spitalnic S, Sucov A. Ludwig’s Angina: a case report and review. J Emerg Med 1995;13:499-503.

3. Freund B, Timon C. Ludwig’s angina: a place for steroid therapy in its management? Oral Health 1992;82:23-25.

1-5 Epiglottitis

Matthew Spencer

Clinical Presentation

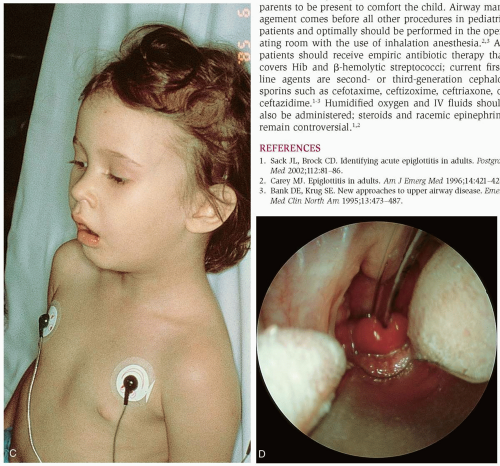

Patients typically present with complaints of fever, sore throat, odynophagia, shortness of breath, and a hoarse or muffled voice.1,2,3 On examination, there is often an associated pharyngitis, anterior neck tenderness, lymphadenopathy, drooling, or stridor.1,2,3 Patients in severe distress may be sitting upright and leaning forward with the mouth open and the jaw thrust forward in what is commonly referred to as the “tripod position.”1,3 There is some variation in presentation between adult and pediatric patients. Adults present most commonly with complaints of sore throat, odynophagia, and anterior neck tenderness, whereas children usually have difficulty breathing, stridor, and a hoarse or muffled voice.1

Epiglottitis was previously considered a disease of children, but with the widespread use of the Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine, it is now seen more often in adults, at a ratio of 0.4 to 1.2 It has an incidence of 0.97 to 1.8 per 100,000 in the adult population and peaks between 35 and 47 years of age.1,2 Epiglottitis is most commonly seen in children between the ages of 7 months and 16 years, with the peak at 2 to 6 years of age.3 The mortality rate is currently less than 1% in children and 6% to 7% in adults.2

Pathophysiology

Epiglottitis is caused by local inflammation and swelling of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and adjacent soft tissue.3 Usually the swelling and inflammation are the result of an infection, although in most cases a single organism cannot be identified.1,2 The organisms most commonly identified are Hib and β-hemolytic streptococci.1,2

Diagnosis

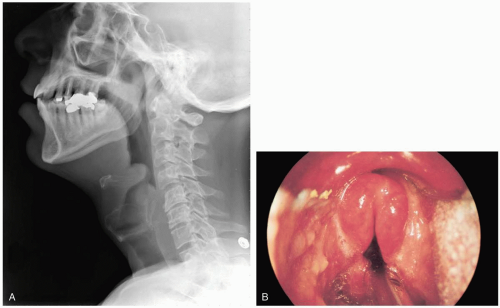

The diagnosis should be suspected in all patients who have relatively acute onset of a severe sore throat with fever and odynophagia. The diagnosis is confirmed by direct or fiberoptic laryngoscopy, which is considered the gold standard but should be performed in a controlled environment by a practitioner who is experienced with advanced airway control techniques.1 In the emergency department, fiberoptic laryngoscopy is considered to be a safe procedure in adults but not in children.2 Pediatric patients with suspected epiglottitis who have moderate to severe symptoms should go immediately to the operating room for simultaneous airway control and diagnosis confirmation.3 Mildly symptomatic pediatric patients may have portable soft tissue neck radiographs taken to help establish the diagnosis but should not leave the direct observation of the emergency physician.3 Lateral soft tissue neck films may show swelling of the

epiglottitis as evidenced by a “thumbprint sign,” swelling of the arytenoids and aryepiglottic folds, a narrowed airway, or prevertebral soft tissue swelling. All of these signs have low sensitivity and specificity except for a decrease in the vallecular airspace (the “vallecular sign”).1,2 Computed tomography (CT) is useful only if the epiglottitis cannot be visualized by laryngoscopy or an abscess is suspected.1

epiglottitis as evidenced by a “thumbprint sign,” swelling of the arytenoids and aryepiglottic folds, a narrowed airway, or prevertebral soft tissue swelling. All of these signs have low sensitivity and specificity except for a decrease in the vallecular airspace (the “vallecular sign”).1,2 Computed tomography (CT) is useful only if the epiglottitis cannot be visualized by laryngoscopy or an abscess is suspected.1

Clinical Complications

The most common and most serious complication is complete airway obstruction leading to respiratory compromise and possibly death.1,2 Bacteremia may lead to the development of sepsis and multiorgan system failure despite antibiotic use.

Management

Airway control is paramount. Only one third of patients require intubation, but practitioners should be prepared for emergency airway management at all times. Many recommend prophylactic intubation.1 In adult patients, intubation with rapid-sequence induction is recommended, but the physician should be prepared for possible emergency cricothyrotomy.2 Children should be placed in a quiet, nonstimulating environment and allowed to assume whatever position they find most comfortable.3 It may be prudent in some cases to allow the parents to be present to comfort the child. Airway management comes before all other procedures in pediatric patients and optimally should be performed in the operating room with the use of inhalation anesthesia.2,3 All patients should receive empiric antibiotic therapy that covers Hib and β-hemolytic streptococci; current first-line agents are second- or third-generation cephalosporins such as cefotaxime, ceftizoxime, ceftriaxone, or ceftazidime.1,2,3 Humidified oxygen and IV fluids should also be administered; steroids and racemic epinephrine remain controversial.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Sack JL, Brock CD. Identifying acute epiglottitis in adults. Postgrad Med 2002;112:81-86.

2. Carey MJ. Epiglottitis in adults. Am J Emerg Med 1996;14:421-424.

3. Bank DE, Krug SE. New approaches to upper airway disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1995;13:473-487.

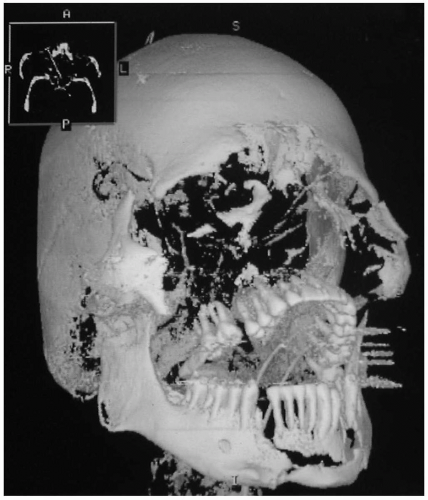

1-6 Orofacial Trauma

Danielle Mailloux

Clinical Presentation

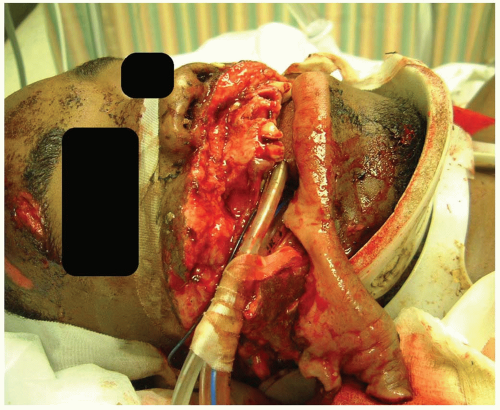

Patients present after injuries that are isolated to the head and face or are part of a more extensive multiple trauma setting. Facial injuries may range from minor abrasions to severe injuries such as gunshot wounds and crush injuries. The presentation of airway compromise in these cases ranges from complete apnea to partial airway obstruction with strider due to debris or foreign matter in the airway. Patients may present with endotracheal tubes that have been incorrectly inserted in the field or that have become dislodged in transit.

Pathophysiology

Facial injuries may be caused by blunt or penetrating trauma. In either case, such injuries require special consideration because of the potential for airway compromise as well as the social and psychological impact that disfiguring injuries of the face can create.1 Complex facial fractures may occur, teeth may be avulsed or broken, and the sensory organs such as the eyes or ears may be damaged.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the history and physical examination. Radiologic studies may be needed to confirm specific injuries.

Clinical Complications

Complications include extensive skin loss, cosmetically deforming injuries, airway compromise due to tissue destruction or foreign materials (e.g., fractured teeth, blood) in the airway, infection, sepsis, and death.

Management

Emergency management of facial trauma should follow advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocols, addressing airway, breathing, and circulation first and then promptly moving on to alleviating pain and caring for local injuries.1 Orofacial fractures often require consultation with ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialists, oral surgeons, ophthalmologists, or plastic surgeons. Empiric antibiotic administration should be considered for intraoral or sinus fractures, contaminated wounds, and injuries involving extensive amounts of devitalized tissue. Tooth fractures with pulp exposure need immediate dental care to prevent necrosis of the neurovascular bundle.2 Most patients with serious facial injuries need admission for airway management, parenteral antibiotic therapy, and surgical repair.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Laskin DM, Best AM. Current trends in the treatment of maxillofacial injuries in the United States. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000;58:207-215.

2. Flores MT, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries. Dent Traumatol 2001;17:193-198.

1-7 Laryngeal Trauma

Karen Lefrak

Clinical Presentation

Signs and symptoms of laryngeal trauma include hoarseness, laryngeal pain, dyspnea, dysphagia, cough, hemoptysis, stridor, tenderness or deformity of the larynx, subcutaneous emphysema, and aphonia.1 Bleeding, expanding hematomas, bruits, and loss of pulses may be associated with vascular injury.

Pathophysiology

Laryngeal trauma is uncommon (1 in 30,000 emergency department visits), and in most of the severe cases the patient dies before arriving at a hospital.1,2,3 Blunt trauma causes compression of the larynx on the anterior cervical bodies with tearing of the cartilage and mucosa. Pediatric injuries differ in that the larynx is more protected by the mandible and the cartilaginous skeleton is more flexible in the pediatric age group.1,2,3

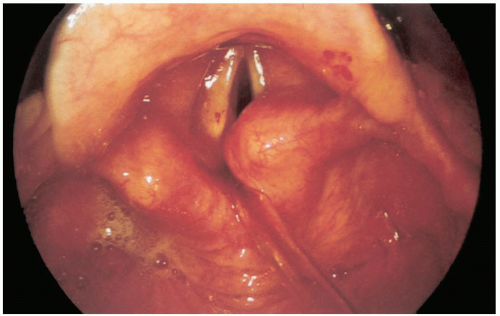

Diagnosis

The history of the trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accident, sports injury, personal assault including strangulation) should help the physician make the diagnosis; a good physical examination is necessary to delineate the seriousness of the injury. Airway problems in a patient with signs of trauma should raise suspicion for laryngeal trauma and must be addressed immediately. Flexible fiberoptic nasopharyngolaryngoscopy is the examination of choice. In stable patients, computed tomography (CT) can be useful for determining the extent of the injury.2

Clinical Complications

A patient with laryngeal trauma may have a difficult airway and require a surgical airway.1 Iatrogenic damage to the larynx can occur during intubation, especially if the stylette extends beyond the length of the endotracheal tube. The small size of the pediatric airway and the potential for large amounts of soft tissue swelling make early treatment essential in this population.1,2,3

Management

Maintaining a patent airway is the hallmark of treatment. Some patients require immediate tracheostomy and open exploration in the operating room. Ear, nose, and throat (ENT) and surgical specialists should be consulted to evaluate the patient as early as possible. Patients with laryngeal trauma should be admitted for airway observation and examination by laryngoscopy.1,2,3

REFERENCES

1. Kleinsasser NH, Priemer FG, Schulze W, Kleinsasser OF. External trauma to the larynx: classification, diagnosis, therapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2000;257:439-444.

2. O’Mara W, Hebert AF. External laryngeal trauma. J La State Med Soc 2000;152:218-222.

3. Verghese ST, Hannallah RS. Pediatric otolaryngologic emergencies. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 2001;19:237-256.

1-8 Subglottic Stenosis

Barry Hahn

Clinical Presentation

Mild cases of subglottic stenosis in children may manifest as repeated episodes of coughing and may erroneously be given the diagnosis of recurrent croup. Adults with mild congenital stenosis are usually asymptomatic and are often diagnosed after a difficult intubation or while undergoing endoscopy for another purpose. Patients with acquired disease may become symptomatic a few days to years after the initial injury.2 These symptoms can include dyspnea, stridor, hoarseness, cough, recurrent pneumonitis, and cyanosis.2

Pathophysiology

Subglottic stenosis is a congenital or acquired narrowing of the region that extends from the lower surface of the true vocal cords to the lower surface of the cricoid cartilage.1,2 Congenital stenosis may be diagnosed only in patients with no history of intubation or laryngeal trauma; it is thought to be secondary to failure of the laryngeal lumen to recanalize properly during embryogenesis.2 Most acquired cases results from laryngoscope injury or pressure necrosis with subsequent scarring.2 Duration of intubation is a primary factor in the development of laryngeal stenosis.1,2 Less common causes of scar formation and stenosis are foreign body, infection, inflammation, and chemical irritation.1,2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree