Key Clinical Questions

What are the red flags that should alert the hospitalist to an adverse cutaneous reaction?

When must the offending drug be discontinued?

How do you treat through a cutaneous reaction?

What is the recommended treatment for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis?

When should you call a dermatology consult?

How do you counsel the patient at time of discharge?

Introduction

Complications of drug therapy are the most common adverse events associated with inpatient admissions and hospital discharge. In the United States, adverse drug events account for up to 140,000 deaths and $136 billion in costs annually. Skin involvement occurs frequently in drug reactions, and may be a presenting manifestation. While most cutaneous reactions are benign and self-limiting, serious adverse cutaneous reactions affect 2% to 3% of inpatients, and lead to 0.1% to 0.3% of hospital fatalities. However, early recognition of clinical findings (Table 142-1) is critical to ensure prompt drug discontinuation and prevent further complications. Risk factors include female gender, age, immunosupression, and greater number of medications. Common culprits are penicillins, sulfonamides, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs).

| Cutaneous signs |

| Blisters |

| Palpable purpura |

| Confluent erythema |

| Epidermal necrosis |

| Ulcers |

| Mucosal involvement |

| Facial edema |

| Systemic signs |

| Fever (>40°C) |

| Skin tenderness |

| Lymphadenopathy |

| Arthralgias |

| Shortness of breath, wheezing |

| Hypotension |

| Laboratory findings |

| Liver function tests > 3x normal |

| Eosinophilia (>1500/mm3) |

| Neutropenia |

Pathophysiology

Cutaneous drug reactions occur by both immunologic and nonimmunologic mechanisms. Genetic predisposition, host characteristics, and probably other poorly understood factors also play important roles.

Nonimmunologic mechanisms are predictable drug reactions, related to overdose, cumulative toxicity, and delayed toxicity. Immunologic mechanisms are often unpredictable. They are classified into four categories. Type I reactions are IgE-mediated responses that activate mast cells, and produce urticaria, angioedema, and hemodynamic instability. Type II reactions involve cytotoxic IgG responses, and often cause blood cell dyscrasias, such as hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia. In type III reactions, immune complex deposition and complement activation produce a vasculitis or serum sickness-like presentation. Finally, type IV reactions are T-cell mediated, and account for most drug exanthems. The character of the skin rash may depend on the type of T-cell response elicited. For example, T-helper 2 responses produce interleukin-4 and -5 secretion and the classic exanthem or morbilliform rash with both erythematous macules and papules (Figure 142-1). A predominantly cytotoxic T-cell response may lead to keratinocyte necrosis and vesicular and pustular eruptions. The T-cell response elicited is determined by the antigenic epitopes of the drug, which depend upon the drug’s chemical reactivity, prior metabolism, and protein binding. In Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), keratinocyte death is also influenced by activation of fatty acid synthetase (Fas) receptors, leading to caspase activation and keratinocyte apoptosis.

Host characteristics that influence drug reactions include alterations in drug metabolism pathways, concurrent medications, immunosuppression, and underlying disease. Patients who have low levels of the enzyme epoxide hydrolase and are taking aromatic anticonvulsants, such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital, accumulate toxic metabolites (arene oxides). This predisposes to the development of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Reactivation of latent viral infections, such as human herpesvirus 6 and 7, also predispose patients to more severe cutaneous drug reactions.

Does This Patient Have an Adverse Cutaneous Drug Reaction?

Mucosal symptoms should always prompt the clinician to consider an early cutaneous drug reaction. Although the incidence of SJS and TEN are low (1.2–6 per million and 0.4–1.2 per million, respectively), they are associated with a combined mortality of 20% to 25%. SJS and TEN represent a clinical spectrum of disease which should not be confused with erythema multiforme. Whereas erythema multiforme is typically a postinfectious process with limited skin findings (Figure 142-2) and low morbidity, SJS/TEN represents a drug-induced systemic spectrum of disease characterized by epidermal necrosis, mucosal membrane involvement, rapid course, and poor prognosis (Table 142-2).

| Drug Reaction | Cutaneous Findings | Mucosal Involvement | Percentage that are Drug Induced (%) | Time Interval from Start of Drug and Onset of Reaction | Mortality (%) | Selected Responsible Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stevens-Johnson syndrome | Dusky, atypical target lesions, < 10% of BSA | Yes | 50 | 1–3 wk | 5 | Sulfonamides Anticonvulsants |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | Confluent erythema, large sheets of necrotic epidermis, >30% BSA | Yes | >80 | 1–3 wk | 30 | NSAIDs Allopurinol |

| DRESS | Facial edema, edematous plaques with perifollicular accentuation | No | 70–90 | 2–6 wk | 5–10 | Anticonvulsants Sulfonamides Allopurinol Minocycline Lamotrigine |

| AGEP | Widespread erythema with nonfollicular sterile pustules | Rare (20%) | 70–90 | <4 days | 1–2 | Beta-lactam antibiotics Macrolides Calcium channel blockers |

Diagnosis should be suspected in the patient with fever, mucosal symptoms, and progressive skin findings. There may be a prodrome of fever, malaise, and upper respiratory tract symptoms. Conjunctival lesions are seen in 85% of cases, and range from asymptomatic hyperemia to keratitis, corneal erosions and pseudomembrane formation. Erosions of the trachea, bronchi, gastrointestinal tract and urethra may also occur, leading to respiratory compromise, impaired alimentation, and painful micturition. Ill-defined erythematous and violaceous macules with two zones of color (atypical target lesions) begin on the upper trunk, and spreads to the extremities over 1 to 4 days. Keratinocyte necrosis produces flaccid blisters that spread with pressure (positive Nikolsky sign) and lead to epidermal sloughing (Figure 142-3). Although controversial, the distinction between SJS and TEN is based on the percentage of body surface area (BSA) with epidermal detachment (<10% SJS, >30% TEN, 10%–30% overlap SJS/TEN). This is important for prognosis and treatment. Laboratory findings may include anemia and lymphopenia. Neutropenia is rare, and associated with worse prognosis.

Diagnosis is clinical, but skin biopsy and immunoflourescence studies may be of value in excluding other nondrug-related bullous and mucosal disorders, such as staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, and paraneoplastic pemphigus. The hospitalist should also ask about risk factors for other blistering disorders, such as thermal burns, phototoxic burns, and pressure blisters.

Previously associated with the aromatic anticonvulsant agents, DRESS is now known to be associated with other medications, including sulfonamides, calcium channel blockers, and allopurinol. Symptoms usually begin 2 to 6 weeks after drug initiation (Table 142-2). Diagnosis should be suspected in the febrile patient with an evolving morbilliform rash (Figure 142-4), lymphadenopathy, eosinophilia (>1500/mm3), atypical lymphocytes, and transaminitis. Macules and papules evolve to form edematous and confluent plaques with perifollicular accentuation. Facial edema is often prominent. The cutaneous findings may resemble SJS if vesicles form secondary to dermal edema. Rarely, small pustules are observed, and the diagnosis may be confused with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Dermatotologic consult and a skin biopsy can help to distinguish these entities (Table 142-3). Evidence of visceral involvement may also be a distinguishing feature of DRESS. Up to 50% of patients develop a potentially life-threatening hepatitis (as compared with 10% of patients with SJS/TEN). Other visceral complications include arthralgias, pericarditis, pulmonary infiltrates, and interstitial nephritis. Reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is frequently found in these patients, and may predispose them to immunosuppression and subsequent bacterial infections. No prognostic factors have been identified. Mortality is 10%.

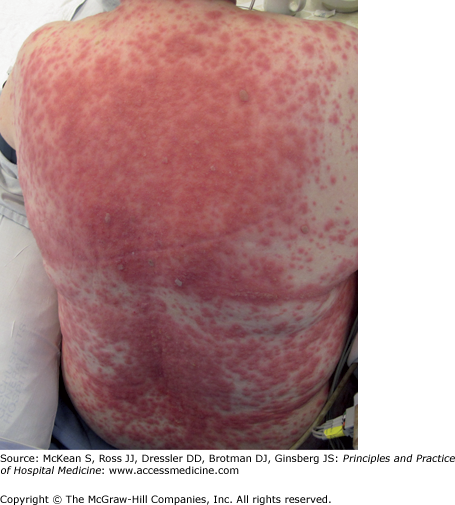

Figure 142-4

(A) Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Erythematous macules and papules coalescing into patches on the back of a patient with early drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. (B) Lesions progress to form edematous plaques with perifollicular accentuation.

| Uncertainty regarding indication for skin biopsy |

| Uncertainty regarding indication for systemic steroids or intravenous immunoglobulin in patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis |

| Clinicopathologic correlation |

Drug-induced pseudolymphoma (Table 142-4) may also present with infiltrated plaques, lymphadenopathy, and similar histologic findings on lymph node biopsy. However, unlike DRESS, pseudolymphoma presents insidiously, lacks systemic involvement, and has a much better prognosis.

| Presentation | Clinical Findings | Time between Start of Drug and Onset of Symptoms | Resolution with Drug Discontinuation | Common Drug Culprits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erythema nodosum | Bilateral, tender, erythematous nodules (mainly on shins) | Weeks | Yes | Oral contraceptive pills Estrogens Sulfonamides Penicillin Bromides Iodides Azathioprine |

| Subacute cutaneous lupus-like reaction | Psoriasiform or annular lesions on trunk, arms, and extensor surfaces | At least 1 year | Sometimes | Hydrochlorothiazide Calcium channel blockers Terbinafine NSAIDs Griseofulvin Docetaxel PUVA Interferon |

| Systemic lupus-like reaction | Fever, weight loss, serositis; cutaneous findings are uncommon | Variable | Yes | Procainamide Hydralazine Chlorpromazine Isoniazid Methyldopa Propylthioruracil Quinidine Practolol D-penicillamine PUVA Minocycline |

| Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis | Erythematous papules and plaques surrounding eccrine glands | 7–14 days | Yes | Cytarabine Mitoxantrone Bleomycin Anthracyclines Methotrexate Cyclophosphamide Acetaminophen |

| Sweet syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatoses) | Painful, erythematous plaques (mainly on face and upper extremities) | Days | Yes |