Adolescent Substance Experimentation and Abuse

Richard Heyman MD, FAAP

INTRODUCTION

The use of mind-altering substances is arguably the most significant and dangerous risk behavior that adolescents exhibit. While the use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs (TAOD) is just one of many problems today’s teens are facing, the distorted thinking that accompanies such use puts children at greater risk than does any other behavioral health problem (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1997). The pediatric primary care provider must play an important part in prevention, identification, and assessment of substance use. This chapter discusses this role in the context of the primary care practice setting.

PATHOLOGY

A variety of factors influence a young person’s decision to experiment with TAOD. Family factors, including tolerance of aberrant behavior and parental role modeling, are certainly critical. Acceptance of use in the community and at school and the degree to which authorities curtail such behavior affect availability and use patterns. Some teens feel compelled to announce their independence through rebelliousness and antisocial behavior. Some teens experiment with mind-altering drugs simply to feel better and obliterate underlying feelings, such as depression, alienation, anger, and anxiety.

Teens who are not activity oriented and have no commonly identified peer group (eg, teammates, Scouts, fellow musicians) may spend inordinate time “hanging out.” When mixed with self-esteem issues and poor motivation, a lack of positive interests is an additional risk factor.

As they consider these risk factors, providers must recognize that substance use is, in fact, a continuum. Many individuals will experiment with mind-altering substances only to abandon use or use infrequently and only under controlled circumstances. Others will develop the pattern of high-reward compulsive use and experience adverse consequences in life, work, relationships, and health. Individual risk and protective factors will play an important role in determining these issues. Display 25-1 provides information that the primary care provider can use when assessing adolescent risk for TAOD use.

DISPLAY 25–1 • Why Young People Start Using Drugs

Family

Lack of supervision

General parental permissiveness

General parental rigidity

Parental role modeling

Biogenetic factors

Community/School

Ready availability and perception of normativeness

Tolerance and acceptance of drugs

Neighborhoods with high crime/use patterns

Lack of commitment to school and future

Absence of attachment to social institutions

Peer Factors

Desire to belong

Peer pressure and acceptance

Lack of attachment

Boredom/group antisocial behavior

Sense of affinity and common interest with group that uses

Self Factors

Sense of rebelliousness

Need for independence

Tendency toward reckless, risk-taking behavior

Acquisition of desired image (usually as portrayed by advertising and media)

Need for increased self-esteem

Desire to look older

Curiosity

Desire to feel better

Source: Heyman, B. B., & Adger, H. (1997). Office approach to drug abuse prevention. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 44(6), 1447–1455.

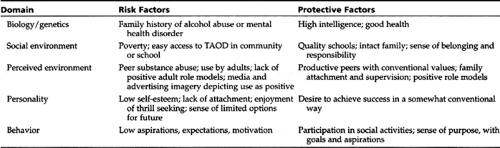

Putting a young person’s choice to use mind-altering substances into the context of other risk behaviors may help to explain the phenomenon further. Jessor (1991) has defined such behaviors as those that jeopardize the individual’s physical, emotional, or psychological health. Examples include truancy, delinquency, inappropriate sexual behavior, TAOD use, membership in gangs, carrying weapons, and even athletic activities pursued in an unsafe manner. Such risk behaviors tend to cluster (because the risk factors for such activities are similar). Thus, the provider identifying one risk behavior should be vigilant about looking for others. Furthermore, for the various kinds of risk factors there are antidotes, or “protective factors.” The net influence of such risk and protective factors helps to determine the behaviors of young people. Jessor (1991) has defined five “domains” of risk and protective factors, presented in Table 25-1. Identification of risk and protective factors in an individual patient is an excellent way to initiate a discussion of risk behaviors and lifestyle. It may furthermore represent an important method of helping to build self-esteem and encourage family activities.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Use of TAOD among adolescents increased significantly throughout the last decades of the 20th century. The “Monitoring the Future” (MTF) study (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1999), conducted annually by the University of Michigan on behalf of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, samples more than 50,000 students in grades 8, 10, and 12 and is generally regarded as a benchmark in assessing usage patterns. Among its 1999 findings was the continued widespread use of alcohol among teenagers. Among eighth graders, 10% admitted to having gotten drunk within the 30 days immediately preceding the survey. Nearly one in four 10th graders had done so, and a third of high school seniors reported so-called “binge drinking” (defined as having had at least four [for women] or five [for men] drinks in a row).

Ninety percent of those people who will ever smoke begin before their 19th birthday. In fact, of adults who are regular smokers, the average age at which they began was 12½ years. Most had progressed to regular use within 2 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1994).

Some 37% of eighth graders admit to having used an illegal drug at some point in their lifetime. That number rises to 50% by 10th grade but goes up only an additional 2% by high school graduation, suggesting that generally, teens make the decision to experiment by age 15. Marijuana is the most commonly used illegal substance (though of course purchase of alcohol and tobacco products is also illegal for the students surveyed). The MTF study consistently shows that 50% of high school seniors have tried marijuana, as have 40% of 10th graders and 22% of eighth graders. While there is slight male predominance and a geographic skew toward the coasts, the numbers have remained remarkably steady throughout the 1990s (Johnston et al., 1999).

Inhalant abuse, the deliberate inhalation of volatile substances, frequently constitutes a young teen’s first exposure to mind-altering drugs. Among eighth graders, 12% admitted

to having used inhalants in the previous year; that number tapers to 9% for 10th graders and 7% for high school seniors. These findings suggest that inhalants are a “starter” drug, with teens moving to other substances as they get more sophisticated (Johnston et al., 1999).

to having used inhalants in the previous year; that number tapers to 9% for 10th graders and 7% for high school seniors. These findings suggest that inhalants are a “starter” drug, with teens moving to other substances as they get more sophisticated (Johnston et al., 1999).

Teens use other illegal drugs commonly as well. Hallucinogens such as LSD showed a pattern of steadily increasing use throughout the 1990s. Chemicals such as MDMA (“ecstasy”) and methamphetamine have become increasingly available and are current drugs of choice for young people exploring the world of mind-altering drugs. Use of narcotics and cocaine also has shown steady upward trends, as purer forms have made alternate routes of administration, such as smoking and nasal inhalation (“snorting”), available.

Most people usually make the decision to use TAOD during the second decade of life. Thus, providers caring for children and teenagers have a major responsibility to identify those at risk and convey the prevention message at every available opportunity.

HISTORY

As one concerned with the total welfare of the individual and family, the primary care provider is perfectly situated to take an active role in the prevention and identification of substance abuse. Ideally, the provider should address this issue throughout his or her relationship with the family.

Age-Appropriate Strategies

During a prenatal visit, issues related to TAOD use should be at the forefront of discussion. The effects on the fetus when a pregnant woman consumes alcohol are well defined and span the gamut from full-blown fetal alcohol syndrome (which includes specific facial defects and cognitive and social problems) to the milder forms of alcohol-related brain damage and neurodevelopmental disorders (see Chap. 24). Pregnant women should not drink: no dosage is safe for a fetus. The provider should emphasize this point repeatedly.

Smoking is hazardous as well. Infants born to mothers who smoke during pregnancy may have underdeveloped lungs and low birth weight. They are at increased risk for sudden infant death syndrome (Schoendorf & Kiely, 1992). Pregnant women should quit smoking, and those caring for them should offer cessation assistance (including nicotine replacement therapy if indicated) (Fiore et al., 2000). Infants and children exposed to environmental tobacco smoke have an increased incidence of upper respiratory and middle ear infections. They tend to experience more episodes of bronchitis and pneumonia and are more likely to have asthma (Etzel, Pattishall, Haley, Fletcher, & Henderson, 1992).

Finally, illegal drugs, including cocaine, narcotics, and even marijuana, may have adverse fetal effects. Decreased placental circulation resulting in low birth weight and developmental

disorders, as well as an infant who is drug-addicted, are sad consequences of maternal use. Providers should advise pregnant women who are using drugs to seek treatment. They always should offer treatment in lieu of taking legal action. Refer to Chapter 24 for more information.

disorders, as well as an infant who is drug-addicted, are sad consequences of maternal use. Providers should advise pregnant women who are using drugs to seek treatment. They always should offer treatment in lieu of taking legal action. Refer to Chapter 24 for more information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree