Chapter 9 Adjunctive treatment for headache and neck pain

what else should you know, and what else might help?

Earlier chapters have offered a comprehensive overview, along with much detail, as to how to understand and manage head and neck pain from a massage/manual therapy perspective.

REMEMBERING ADAPTATION

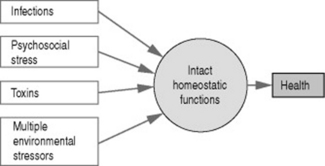

1. All health problems can benefit from reducing the adaptive load(s) being coped with, i.e., all the stresses of living, whether these be:

2. Additionally, all health problems benefit from improved functionality – better circulation, mobility, strength, neural function, breathing, balance, posture, etc.

3. If the overall adaptive load is reduced, and/or if functions are improved, the self-regulating/self-repair systems and mechanisms of the body will be able to operate more effectively.

GENERAL ADAPTATION SEQUENCE (Figure 9.2)

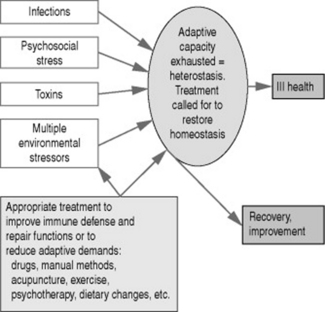

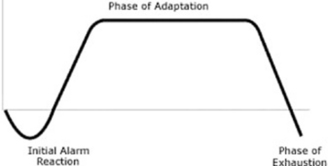

Selye’s (1943) general adaptation syndrome describes a process in which the individual, with his or her unique inherited and acquired characteristics, is responding to multiple variable or constant adaptive demands, resulting in:

• an initial alarm stage. An example of this is the ‘fight or flight’ (sympathetic arousal) response, which might be triggered by a single stress event or by a number of minor stressors acting simultaneously (Figure 9.3). If the stressor(s) continues to operate, the body’s defense mechanisms move to what is known as:

• the adaptation phase, which continues until the ability of the body to compensate further is exhausted. This can be expressed as homeostatic exhaustion, or a stage of heterostasis, where adaptation potential fails (think of a piece of elastic that has been stretched until it starts to fray, and eventually snaps). When this occurs we have reached:

• the stage of exhaustion. The individual’s self-regulating/self-repair potentials will be exhausted (or severely strained) and chronic symptoms and frank disease will follow. At this stage homeostatic mechanisms may fail, decompensation features emerge, and treatment to slow, modify or reverse the process is called for (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.2 After the initial alarm phase (see Figure 9.3), if stresses continue, as they inevitably do, to one degree or another, the adaptation phase of the general adaptation syndrome (GAS) commences. This may last many years. As time passes functional changes appear (stiffness, restriction, weakness, balance problems, degrees of pain, etc.). When adaptation potential is eventually exhausted, and the phase of exhaustion starts, more obvious symptoms are experienced. At this stage homeostasis/self-regulation is no longer able to operate efficiently, and a state of heterostasis exists (see Figure 9.4B), where something (treatment, altered behavior patterns, etc.) is required in order to restore homeostasis, and improved adaptive potential, i.e. self-regulation. This is, however, not always possible, as damage (e.g., arthritis) may have progressed too far for more than modest improvement to be possible.

(Adapted from Selye 1943)

WHAT HELPS?

Those that will be considered, later in this chapter, in relation to headache and neck pain include:

• acupuncture (what you should know about this)

• emotion/stress management and relaxation methods

• high-velocity manipulation (what you should know about this)

• lifestyle changes, including nutrition and exercise

• self-care (including balance training)

GENERAL OBJECTIVES BASED ON AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE ADAPTATION PROCESS

• to identify and help the individual to reduce the adaptive demands – the habits of life that are helping to create (or aggravate, or maintain) the dysfunctional state that allows minor trigger factors to activate the symptoms

• to enhance functionality by improving posture, breathing, mobility, etc.

• to ease symptoms without adding to the person’s adaptive burden, emphasizing the importance of remaining aware of just how sensitive and vulnerable this person is

• to support self-repair, self-regeneration, self-healing processes

• to take account of the whole person, the lifestyle, habits, attitudes and behavior – and not just the symptoms

• to keep in mind that the more complex the condition, and/or the more sensitive and unwell the individual is, the less that should be done therapeutically at any given time

• to try to focus on causes – and, above all,

INTERACTING CAUSES

• Being female: Women are over-represented not only in migraine but also in tension headaches (Buchgreitz et al 2006).

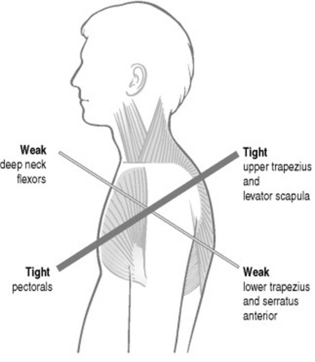

• Poor posture, or poor patterns of use (overuse, misuse, microtrauma, etc.) that frequently, or repetitively, stress the tissues of the head–neck–shoulder region, involving a build-up of musculoligamentous tension in the muscles, with the inevitable emergence of myofascial trigger points capable of referring pain into the head and neck (Giacomini et al 2004). Among the commonest features are tighter (‘harder’) muscles than usual (Ashina et al 1999) and a forward head posture (Moore 2004, Zito et al 2006) (see Figure 9.5, and also Figures 9.9 and 9.10).

• Residual chronic structural and functional changes affecting joint or soft tissue status, following major trauma such as whiplash, or degenerative changes such as osteoarthritis, including excessive muscle tightness/‘hardness’ (Kashima et al 2006, Zito et al 2006).

• Emotional distress, whether intermittent or constant, including anger and depression (Materazzo et al 2000), or depression (Lipchik & Penzien 2004), are all associated with increased headache incidence. Some studies have found that psychological symptoms are more related to associated symptoms (digestive, sleep, fatigue, etc.) than with the headaches themselves (Mongini et al 2006).

• Allergy: People with allergies such as eczema, who also suffered intense chronic headache, were shown to improve both in terms of their allergies as well as their headaches, when an ‘antihistamine’ diet was followed: avoiding alcohol, matured or fermented food rich in histamine (such as old cheese, fish, cured sausages), bread products containing yeast, vegetables such as spinach and tomatoes, or histamine-liberating fruits such as citrus (Maintz et al 2006).

• Nutritional imbalances (toxicity, deficiency):

• Hormonal factors: Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone have long been considered as well-known migraine triggers, probably as a result of genetic predisposition (Colson et al 2006).

• Underlying pathology: Conditions such as diabetes and high cholesterol levels (hypercholesterolemia) have been shown to be closely associated with headache (Davila & Hlaing 2007).

• Pregnancy – especially if high blood pressure is also a factor (Facchinetti et al 2005).

• Sensitization: As tissues respond to a variety of ongoing or periodic adaptive demands, a degree of sensitization may occur, allowing minor stress factors (of any sort) to provoke pain. This feature of what is known as central sensitization is common to all forms of chronic pain, including headaches and neck pain, and is discussed later in this chapter (Bendtsen et al 1996).

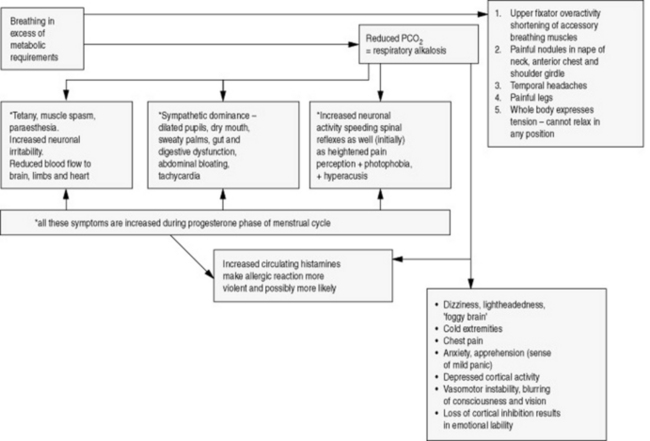

• Breathing pattern disorders: The common habit of upper chest breathing imposes physical stress (overuse) on the accessory breathing muscles (such as scalenes, sternocleidomastoid, upper trapezius), as well as producing a wide range of biochemical and emotional changes (Figure 9.6). Breathing imbalances associated with sleep are directly linked to headaches (Chervin et al 2000). Jennum & Jensen (2002) state: ‘Primary sleep disorders such as insomnia, including sleep disordered breathing, are all associated with and may cause headache.’ They note that obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) leads to morning headaches.

BACKGROUND

We can see that headaches, and their associated symptoms, may emerge from a background involving very different stressors, interacting with the unique genetic, biomechanical, biochemical, and psychosocial characteristics of the individual.

THE SENSITIZATION MODEL

Bendtsen (2000) has described a model that explains the process leading to tension-type headache. He points to a process of central sensitization (facilitation) that occurs in both spinal and pericranial tissues, after prolonged bombardment of pain messages from pain receptors (nociceptors) in distant myofascial tissues.

Once they exist, areas of facilitation/sensitization appear to be capable of being irritated by stressors of all types – physical, chemical or psychological – even if there is no direct or obvious impact on the sensitized area (Bendtsen & Ashina 2000).

An adaptation example – leg length and headaches?

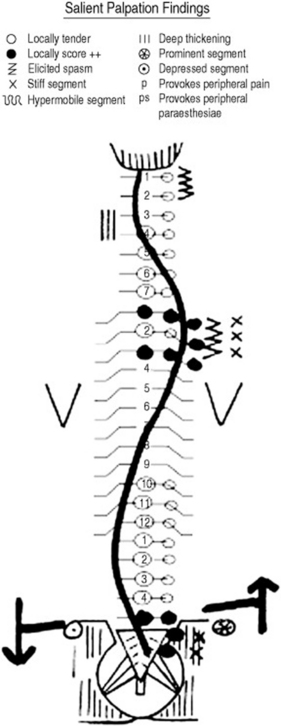

Janda (1988) describes the adaptive changes resulting from the presence of a significant degree of leg shortness (say ¾ inch/2 cm):

• A short leg inevitably leads to an altered pelvic position.

• This unlevels the sacral base and leads to scoliosis.

• As the spine adapts, a sequence of compensations is likely to lead to joint dysfunction at the cervicocranial junction.

• This inevitably results in compensatory activity of the small cervico-occipital muscles (such as rectus capitis posterior minor) and a modified head position.

• Further compensation occurs involving most of the neck musculature, some of which will lead to increased muscle tone and possibly muscle spasm.

• A sequence follows of compensation and adaptation responses in many muscles, ligaments and joints of the region, followed by the development of a variety of possible syndromes and symptoms involving the head, neck, temporomandibular joint, shoulder and/or the arm.

Whether the short leg is anatomic or functional (i.e., where there is a primary sacroiliac dysfunction that alters the position on the ilia, and therefore creates an apparent change in leg length), the changes described by Janda will occur. The difference is that with a functional change, correction of the sacroiliac joint problem should reduce the chain reaction of adaptational modifications, whereas with a true anatomic short leg, choices would be far more limited (e.g., requiring a heel and sole lift) (see Figure 9.7 for an example of a short-leg-induced scoliosis corrected by a heel lift).

Another example

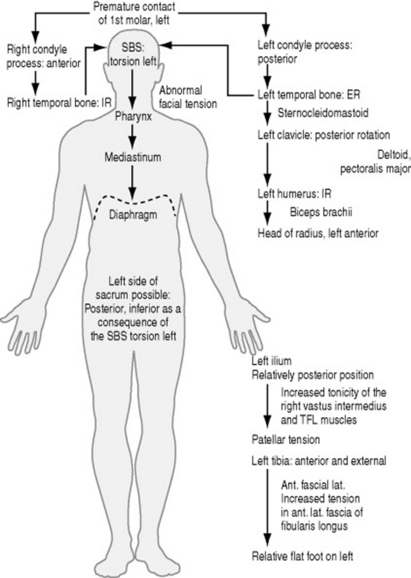

Liem (2004) has explained a sequence that results from a degree of malocclusion, involving, as an example, the first molar on the left, where premature contact occurs on bringing the teeth together.

Figure 9.8 shows something of the chain reaction of adaptations resulting from this apparently minor structural imbalance, in which cranial modifications absorb the stresses of this dental misalignment, followed by bodywide muscular and fascial adaptations that also include osseous changes involving the left clavicle, humerus, radius, ilium, patella, tibia, and foot.

Janda’s example of adaptation and facial pain

Janda (1982) describes a typical postural pattern in an individual with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) problems, involving changes in upper trapezius, levator scapulae, scalenii, sternocleidomastoid, suprahyoid, lateral and medial pterygoid, masseter and temporalis muscles. In this pattern (described below) all these muscles will show a tendency to tighten and/or to develop tendencies to spasm, tenderness, and the evolution of trigger points.

The postural pattern associated with TMJ dysfunction might therefore involve:

1. hyperextension of the knees

2. increased anterior tilt of the pelvis

5. rounded shoulders and winged (rotated and abducted) scapulae

7. compensatory overactivity of upper trapezius and levator scapulae

8. forward head position resulting in opening of the mouth and retraction of the mandible

9. intervertebral joint stress in the cervical spine

WHAT’s TO BE DONE?

In any given case your role is to try to identify what can be done to help ease the current headache (see previous chapters, and also Box 9.1), as well as what might be done, or what the person might do, to reduce the likelihood of further symptomatic episodes.

Box 9.1 Soft tissue modalities in a clinical management sequence

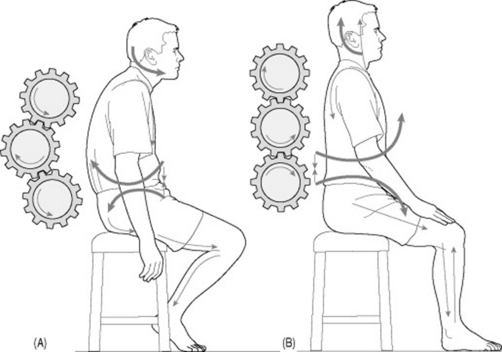

1. Identify local and general imbalances that may be contributing to the symptoms being presented (posture, patterns of use, local dysfunction).

2. Identify, relax, and stretch overactive, tight muscles, using massage and possibly muscle energy techniques (MET), positional release techniques (PRT), myofascial release techniques (MRT) and others.

3. Mobilize restricted joints (possibly using MET, PRT).

4. Facilitate and strengthen weak muscles.

5. Re-educate (exercises, training, etc.) movement patterns, posture and/or breathing function.

This sequence is based on sound biomechanical principles (Jull & Janda 1987, Lewit 1999) and serves as a useful basis for care and rehabilitation of the patient with musculoskeletal problems that may be contributing to neck pain or headache. A variety of soft tissue normalization methods can be incorporated into this model (DiGiovanna 1991, Greenman 1989).

In these examples, using a biomechanical model of care, incorporating massage and appropriate soft tissue modalities (see Box 9.1) and rehabilitation strategies (posture, breathing, etc.) should certainly help to alter/improve the soft tissue status, enhance circulation and lymphatic drainage, and – if appropriate – assist in the deactivating of trigger points that may be contributing to the headache.

A broader model of care

The biomechanical model outlined in Box 9.1 is one way of managing such problems. Other proposed models for effective care of musculoskeletal dysfunction incorporate somatic, as well as behavioral, features. For example, Langevin & Sherman (2006) have described a model in which a broader therapeutic approach to musculoskeletal dysfunction in general can be understood. This is an ‘integrative mechanistic’model that addresses both behavioral and structural aspects, as well as pain psychology, postural control, and neuroplasticity.

In this way long-term preventive approaches might also include:

• enhanced standing, sitting, and sleep postures

• greater care over work and leisure activity postures and positions (ergonomics) – for example, consider the often prolonged periods of distorted or strained positioning involved in people working in dentistry, hairdressing, construction, massage, house-painting, automobile repair, plumbing, gardening, nursing, home-making, running, jumping, throwing, climbing, etc. Consider also that in such situations repetitive and/or prolonged stresses may be being loaded onto already compromised tissues, which may have become shortened and/or weakened, fibrotic, indurated or in some other way dysfunctional, long before current stress patterns were imposed

• breathing rehabilitation strategies

• stress management (see Box 9.2), including learning relaxation techniques

• counseling or psychotherapy, if appropriate

• mobilization of restricted cervical and thoracic structures – including self-help measures (see below)

• stretching shortened associated musculature – including self-help measures (see below)