Chapter Nine Adjunctive approaches and understanding and addressing breathing disorders

Adjunctive approaches

This chapter will focus on adjunctive approaches that may prove useful in management of the symptoms of pain. A specific emphasis will be placed on understanding the role of breathing as a pain management tool with guidelines for addressing dysfunctional breathing during the massage. The adjunctive approaches can either be directly integrated into massage application or provided as self-care.

Another useful reminder is that not everything is fixable. Although we are always working with the aim of enhancing self-regulation, some changes – osteoarthritis, for example – or the circulatory or soft-tissue effects of old age, may involve such chronic change that the best we can hope for is a modest improvement, or a slowing of what may be inevitable decline. In such instances maintenance of the present state may be a realistic therapeutic objective.

Acupuncture (what you should know about this)

Acupressure methods, as used in shiatsu and Thai massage (Palanjian 2004), have very similar effects to those achieved by acupuncture.

Aromatherapy

A clinical placebo controlled trial involving individuals with depression as a major feature, but with secondary symptoms of sleep disturbance and chronic headaches, were treated with massage and essential oils (selected from bergamot, clary sage, lemon, lavender, Roman chamomile, geranium, rose, sandalwood, and jasmine) in a hospital setting (Lemon 2004).

The control group received massage using grape seed oil. The essential oils selected for the treatment group had been previously shown to offer benefit in the conditions presented (Lawless 1994).

In the hospital study it was found that:

Emotion/stress management and relaxation methods

The neutral bath: for inducing deep relaxation/sleep enhancement

Instructions

• Lie down in the bath so that, if possible, water covers your shoulders.

• Rest your head on a towel or sponge.

• A bath thermometer should be in the water and the temperature should not be allowed to drop below 92°F/33.3°C.

• It can be topped up periodically, but must not exceed the 97°F/36.1°C limit.

• The duration of the bath should be anything from 30 minutes to 2 hours – the longer the better as far as relaxation effects are concerned.

Progressive muscular relaxation exercise (time required approximately 20 minutes) (Carroll & Seers 1998)

Autogenic training and (Erickson’s) progressive muscular relaxation were evaluated for its benefits in patients with fibromyalgia (Rucco et al 1995). The researchers reported that:

Instructions

• Lie comfortably on a draft-free carpeted floor, arms and legs outstretched.

• Tense the fist of your dominant hand and hold tight for 10 seconds.

• Let go the tense fist and enjoy the sense of release for 10 seconds.

• Repeat this, and then do the same with the other hand.

• Go to your dominant side foot and draw the toes upwards towards the knee, tightening the muscles. Hold this for 10 seconds.

• Release and relax for 10–15 seconds, then repeat once before going to the other foot.

• Perform a similar sequence in at least 5 other sites (each on both sides of the body, making 10 more sites) such as:

Other muscles can also be contracted by working out just what tightens them.

Results should come quickly but only if the exercise is performed regularly!

Autogenic training (Rucco et al 1995)

Every day, for ten minutes do the following:

• Lie comfortably, a cushion under the head, knees bent, eyes closed.

• Focus attention on your dominant (say, right) hand/arm and silently say, ‘My right arm (or hand) feels heavy.’

• Sense the arm relaxed and heavy. Feel its weight. For about a minute repeat the affirmation, ‘My arm/hand feels heavy,’ several times, and try to stay focused on its heaviness.

• You may lose focus as your mind wanders periodically. This is normal, so don’t be upset, just return to your arm and its heaviness.

• Try to enjoy the sense of release – of letting go – that comes with this heavy feeling.

• Next focus on your left hand/arm and do exactly the same thing for about a minute.

• Move to the left leg, and then the right leg, for about a minute each, with similar messages, focusing attention for about 1 minute each.

• Return to your right hand/arm and this time affirm a message which says, ‘My hand is feeling warm (or hot).’

• After a minute go to the left hand/arm, then the left leg, and then finally the right leg, each time with the ‘warming’ message and focused attention. If warmth is sensed, feel it spread, and enjoy it.

• Finally focus on your forehead and affirm that it feels cool and refreshed. Hold this thought for about 1 minute.

• Finish by clenching your fists, bending your elbows and stretching out your arms. The exercise is complete.

Repeat the whole exercise at least once a day and you will gradually be able to stay focused on each region and sensation.

Using autogenics to ease pain

• If pain relates to poor circulation, a ‘warmth’ instruction can be used to improve it.

• If there is inflammation, this can be eased by ‘thinking’ the area ‘cool.’

• You can focus on any area – for example, visualizing a stiff joint easing and moving, or a congested swollen area returning to normality.

Ergonomics

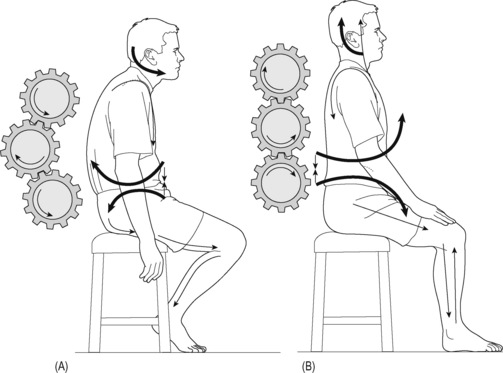

The concept of specific adaptation to imposed demands is essential in understanding how the human biomechanical design evolved, and what interventions can be made to enhance biomechanics – whether through treatment, stretching programs, or corrective or performance based exercise (Figs 9.1 and 9.2).

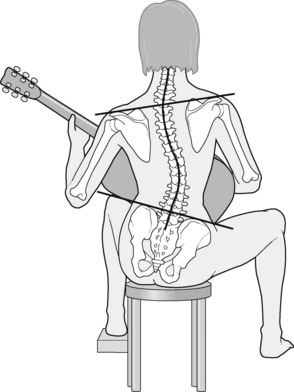

Questions should be asked about work and recreation positions and activities. In addition, sleeping, driving, and standing postures should be evaluated, and advice offered, or referral made to suitably trained and licensed professionals for such advice. Figure 9.2 shows a possibly unavoidable posture for someone playing the guitar. Treatment of the stressed and distressed tissues, along with home stretching advice, should effectively reduce the soft tissue changes resulting from being in such a position for lengthy periods.

High velocity manipulation (what you should know about this)

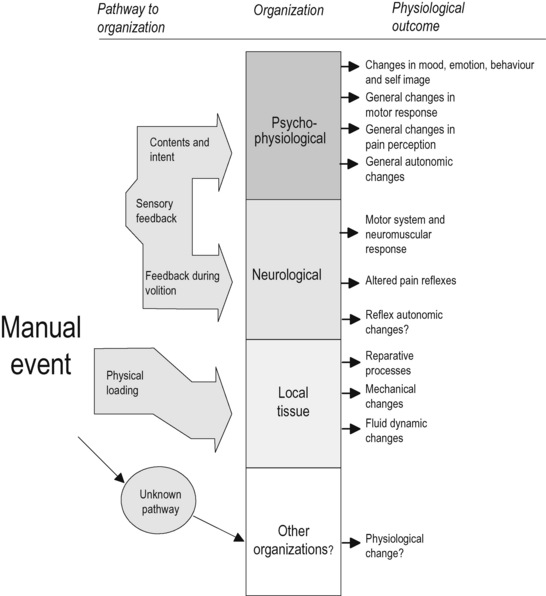

The therapeutic effects of HVLA are summarized in Figure 9.3.

Safety

Most issues of safety in relation to the use of HVLA involve the cervical spine. While practitioners using HVLA report that minor side effects (local discomfort, headache, tiredness, radiating discomfort) occur after approximately 33% of visits, these are usually no longer present after 24 hours (Malone et al 2002).

Major complications from cervical manipulation are rare (between 1 in 400 000 and 1 in 10 million; Shekelle et al 1992) but can be serious (Coulter et al 1996).

It is worth acknowledging that complications resulting from most other forms of treatment of neck pain, for which data are available, are estimated to be higher than those for manipulation. Haldeman et al (2002) note that in reviewing nearly 400 cases of vertebrobasilar artery dissection, it was not possible to identify a specific neck movement, type of manipulation, or trauma that would be considered the offending activity in the majority of cases.

An editorial (Hill 2003) in the Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences stated:

Constitutional hydrotherapy (Watrous 1996, Blake 2006)

The method described below is adapted for home use. (Note: Help is required to apply HC.)

Materials required

• A full-sized sheet folded in two, or two single sheets.

• Two blankets (wool if possible).

• Three bath towels (when folded in two each should be able to reach side to side and from shoulders to hips).

• One hand towel (each should, as a single layer, be the same size as the large towel folded in two).

Method

• Undress and lie face up between the sheets and under the blanket.

• Whoever is assisting you should place two hot folded bath towels (i.e. four layers of damp/hot toweling) to cover the trunk, shoulders to hips.

• Cover the towels with a sheet and blanket and leave for 5 minutes.

• Your helper then returns with a single layer (small) hot towel and a single layer cold towel.

• The ‘new’ hot towel is placed on top of the four ‘old’ hot towels, and these are ‘flipped over’ so that the new hot towel is on the skin. The used/old towels are discarded.

• Immediately place the cold towel onto new hot towel, and flip again, so that the cold towel is on the skin. Remove and discard the single hot towel.

• Cover the whole body with a sheet and leave for 10 minutes or until the cold towel warms up.

• Remove the previously cold, now warm, towel and turn onto stomach.

Suggestions and notes

• If using a bed take precautions not to get this wet.

• ‘Hot’ water in this context is a temperature high enough to prevent you leaving your hand in it for more than 5 seconds.

• The coldest water from a running tap is adequate for the ‘cold’ towel. On hot days, adding ice to the water in which this towel is rung out is acceptable if the temperature contrast is acceptable to the patient.

• If the person being treated feels cold after the cold towel is placed, use back massage, foot, or hand massage (through the blanket and towel) to warm up.

• Apply daily or twice daily if pain is chronic.

• There are no contraindications to constitutional hydrotherapy.

Hot mustard foot bath

The hydrostatic effect in hydrotherapy involves the shifting of fluid from one part of the body to another. The hydrostatic effect can be used clinically in the treatment of conditions in which it is suspected that there is a locally congested area which is giving rise to symptoms, such as congestive headache or sinusitis. Dilation of the blood vessels of the skin at some area distal and inferior (e.g. feet) to the area affected (e.g. head) can be effective in relieving congested tissues (Blake 2008).

Self-help instructions for tension headache home hydrotherapy method

This is a traditional naturopathic hydrotherapy method for tension headaches.

• Place 9 liters (2 gallons) of hot water (not scalding!) into a bowl large enough for both feet to rest in.

• Stir 1–2 teaspoons of mustard powder into this and put your feet, up to the ankles, in the water.

• Wrap a large bag of frozen peas in a towel and place this behind your neck (if you use an upright chair and place this against a wall, you can lean back onto the towel containing the peas), or

• Wrap a damp (not dripping) cold towel around your head.

• Spend at least 10 minutes in this position and then lie down and rest.

Lifestyle changes, including nutrition and exercise

Western man’s diet today is excessive in high animal proteins, cooked, rich and fatty – high level of carbohydrates, largely derived from refined ingredients such as white bread, buns, cakes, biscuits, pastries, puddings, pies, as well as white sugar, sweets, chocolates, preserves and jams; cooked refined porridge, processed cereals, white rice, ice-cream etc., fluids from tea, coffee, cocoa, alcohol and synthetic and artificially sweetened, bottled drinks – fried, pickled, preserved, cured, smoked, salted and tinned meats and fish; dairy products that are pasteurized and distorted – all of which contribute to the noxious encumbrances and the deficiencies contributing to today’s tragic state of ill-health. And on top of that, many other items of civilized foods are ‘doctored’ by colouring, flavouring, preserving, sweetening, salting, chemicalizing and generally overcooking, to create ‘foodless’ material, that in laboratory experiments causes rats to lose their hair and teeth, to abort their young, to become irritable, pugnacious and cannibalistic – and in ludicrous seriousness causes pain-ridden humans to become pouchy, grouchy, with falling hair, rotting teeth, poached-egg eyes, pickled livers, bleeding piles, and no idea what eating is all about. (Chaitow 1980)

Posture

Experts in postural dysfunction, such as Janda (1982) and Lewit (1999), identified patterns of posture that were described as ‘crossed pattern syndromes,’ as well as a ‘layered syndrome.’ These crossed patterns demonstrate the imbalances that occur as antagonists become inhibited due to the overactivity of specific postural muscles. The effect would be to create an environment conducive to pain and dysfunction.

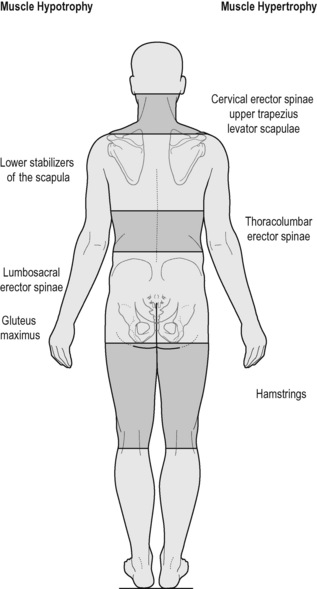

Layered syndrome (see Fig. 9.4)

The muscular changes here include:

– Shortened: hamstrings, thoracolumbar erectors, upper fibers of trapezius, levator scapulae, suboccipitals, hip flexors (rectus femoris and iliopsoas).

– Lengthened/weakened/inhibited: gluteus maximus, upper thoracic erectors, lower/middle fibers of trapezius.

Postural rehabilitation

• Normalization of soft tissue dysfunction, including abnormal tension and fibrosis. Treatment methods might include massage, neuromuscular techniques, muscle energy techniques, myofascial release, positional release techniques and/or articulation/mobilization, and/or other stretching procedures, such as yoga.

• Deactivation of active myofascial trigger points, possibly involving massage, neuromuscular techniques, muscle energy techniques, myofascial release, positional release techniques, or spray-and-stretch. Appropriately trained and licensed practitioners might also use injection, dry needling, or acupuncture in order to deactivate trigger points.

• Strengthening weakened structures, involving exercise and rehabilitation methods, such as Pilates.

• Proprioceptive reeducation, utilizing manual therapy methods (e.g. balance retraining – see below – and/or use of balance sandals or a wobble board) as well as spinal stabilization exercises and methods such as those devised by Feldenkrais, Hanna, Pilates, Trager, and others.

• Postural retraining using Alexander technique (referral to specialized teachers of this method is recommended) as well as a breathing reeducation (see notes below) as well as yoga, tai chi, and similar systems.

• Ergonomic, nutritional, and stress management strategies (see below).

• Psychotherapy, counseling, or pain management techniques, such as cognitive behavior therapy, that may require specific referral to trained and licensed experts.

• Occupational therapy that specializes in activating healthy coping mechanisms, determining functional capacity, and increasing activity that will help return the individual to a greater level of self-reliance and quality of life (Lewthwaite 1990).

• Appropriate exercise strategies to overcome deconditioning (Liebenson 1996).

A team approach to postural rehabilitation is called for where referral and cooperation allow the best outcome to be achieved.

Self-care (including balance training)

Single leg stance balance test (Bohannon et al 1984)

A reliable procedure for information regarding balance/stability as well as being useful for retraining if necessary that requires no equipment other than a timer is described below (see Fig. 9.5).

Procedure

• The person is asked to stand, barefoot, and to raise one foot up without touching it to the support leg.

• The knee can be raised to any comfortable height.

• The person is then asked to balance on one leg for up to 30 seconds with eyes open.

• After standing on one leg in this way, standing on the other should be tested.

• When single leg, standing with eyes open, is successful for 30 seconds the person is asked to identify a feature/spot on a wall opposite, and to then close the eyes while visualizing that spot.

• An attempt should be made to balance for 30 seconds, before switching legs and repeating the exercise.

Scoring

The time is recorded when any of the following occurs:

• The raised foot touches the ground or more than lightly touches the other leg.

• The stance foot changes (shifts) position or toes rise.

• There is hopping on the stance leg.

• The hands touch anything other than the person’s own body.

Breathing

Research on breathing as a pain intervention

Heart rate variability (HRV) is an emerging variable in the study of pain. It is a measure of cardiac activity sensitive to balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic influence, and can also be used as a biofeedback signal to help the patient regulate and balance the autonomic nervous system (ANS) by altering breathing. ANS imbalance is implicated in irritable bowel syndrome, for example (Mazur 2007). A study by Appelhans (2008), using an applied thermal pain stimulus and frequency domain based spectral analysis with 59 normal subjects, found an inverse relationship between greater low frequency HRV and pain intensity, including unpleasantness ratings. The low frequency band (0.04–0.15 Hz) increases with both regular breathing and emotional calmness, and generally correlates with ANS balance and cardiovascular health.

An experimental pain stimulus such as heat or intra-muscular hypertonic saline infusions can be adjusted and administered in order to measure pain thresholds. For example (Chalaye et al 2009), to study variability of pain tolerance and thresholds, the researchers applied thermal pain stimuli to subjects under two breathing conditions, distraction and feedback of HRV. Compared with a 16/min breathing rate, slow deep breathing at a rate of 6/min resulted in better pain tolerance and higher pain thresholds. Increase in HRV correlates with increased vagal tone and general lowering of arousal.

Tan et al (2009), using data from US war veterans suffering from chronic pain and other injuries, used a time domain analysis of HRV. A −0.46 correlation was found between HRV (in this case, SDNN, a time measure of variability) and presence of pain. So in these two samples, a variable associated with breathing quality was also associated with presence of pain or sensitivity to pain. This is significant because HRV is a widely used biofeedback modality, and learning to raise low frequency HRV by regulating breathing may have favorable effects on pain and homoeostasis in general.

Zautra et al (2010), comparing fibromyalgia patients with healthy controls, assigned slow breathing to volunteers subjected to controlled thermal stimuli. ‘Slow breathing’ was defined as breathing at one-half their normal rate. In general, slow breathing reduced pain intensity and unpleasantness more than normal breathing. The authors cited these results as support for Zen meditation and yogic breathing as a way to combat pain.

Pain may seem like a simple unitary sensation, but it has several facets, some mainly psychological. Using a brief intervention, Downey and Zun (2009) instructed patients in an emergency department to handle their pain by slow deep breathing. By self-report, no significant reduction in pain resulted, but the patients reported significant improvements in rapport with treating physicians, greater willingness to follow the medical recommendations, and conclusions that the intervention was useful.

Another study (Flink et al 2009) of back pain patients showed that the effect of practicing breathing exercises for 3 weeks was not so much on reducing pain levels as lowering catastrophizing and pain related distress, along with greater acceptance of the pain condition.

Stress and breathing

Another aspect of the interaction between breathing and emotion is the location of breathing in the body. Optimal breathing most often involves the diaphragm flattening on inhalation and the lower ribcage expanding outward, with the abdomen also expanding forward and laterally. Chest breathing, by contrast, minimizes the diaphragm action and substitutes pectoral, scalene, trapezius, SCM, and upper intercostal muscles. This latter type of breathing is more prevalent during emotional stress and preparation for action. Thoracic breathing actually produces increases in cardiac output and heart rate (Hurwitz 1981). During emergency action, this kind of breathing would provide an advantage. The diaphragm also contributes to spinal stabilization, so during action preparation it is likely to be diverted from breathing duties.

Repercussions of breathing pattern disorders

Breathing pattern disorders (BPD) have been shown to potentially have multiple, bodywide, influences, summarized below. For example, Nixon and Andrews (1996) vividly summarize a common situation applying to the individual with BPD tendencies:

BPD (with hyperventilation as the extreme of this) may influence health by:

• altering blood pH, creating respiratory alkalosis (Pryor & Prasad 2002, Celotto et al 2008)

• inducing increased sympathetic arousal, altering neuronal function – including motor control (Dempsey et al 2002, Brotto et al 2009)

• encouraging a sense of apprehension and anxiety, affecting balance, muscle tone, and motor control (Rhudy & Meagher 2000, Balaban & Thayer 2001, Van Dieën et al 2003)

• depleting Ca and Mg ions, enhancing sensitization, and encouraging reduced pain threshold and the evolution of myofascial trigger points (Gardner 1996, Travell & Simons 1999, (Cimino et al 2000, Schleifer et al 2002)

• triggering smooth muscle cell constriction, leading to vasoconstriction and/or spasm – including colon spasm (Ford et al 1995, Yokoyama et al 2008, Debreczeni et al 2009) or pseudoangina (Evans 1980, Wilke et al 1999)

• reducing oxygen release to cells, tissues, and brain (Bohr effect) so encouraging ischemia, fatigue, pain, and the evolution of myofascial trigger points (Freeman & Nixon 1985, Suwa 1995)

• creating biomechanical overuse stresses and compromising core stability and posture (Lewit 1980, 1999, Haugstad et al 2006b, Hodges et al 2007).

Varieties of BPD

Courtney et al (2008, 2009a) suggest a distinction can be made between those BPD that appear to have a predominately biomechanical nature – where the patient may have a ‘perception of inappropriate, or restricted, breathing,’ as distinguished from BPDs where a chemoreceptor etiology may exist, for example linked to reported sensations such as there being a ‘lack of air.’ Courtney et al (2008) note that the sensory quality of ‘air hunger’ or ‘urge to breathe’ is most strongly linked to changes in blood gases, such as CO2, or changes in the respiratory drive deriving from central and peripheral afferent input. These sensations may be distinguishable from breathing sensations related to the effort of breathing, which are biomechanical in nature (Simon et al 1989, Banzett et al 1990, Lansing 2000, Chaitow et al 2002).

Questionnaires exist for assessment of these BPD variations – with the Nijmegen Questionnaire (NQ; see Box 9.4) (van Dixhoorn & Duivenvoorden 1985) having greater relevance for hyperventilation, and the Self-Evaluation Breathing Questionnaire (SEBQ) (Courtney 2009b) discriminating between the chemoreceptor and the biomechanical variations of BPD.

Irrespective of the major etiological features (see above and listed below), chronic BPD results in altered function and, in time, structure, of accessory and obligatory respiratory muscles. It is suggested that these should attract therapeutic attention in any attempt to normalize breathing, or the distant effects of BPD on pelvic function (Chaitow 2004). The general massage protocol presented in Chapter 8 can be modified to specifically address breathing function.