CHAPTER 13 Adjunctive Analgesics

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

Adjunctive analgesics is a term used to describe medications that can be used for pain relief but whose primary indication is not related to pain. This term is also used to differentiate these types of analgesics from the more commonly used drug classes such as simple analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and muscle relaxants, which are collectively termed common analgesics in this textbook and discussed in Chapter 11, as well as opioid analgesics, which are discussed in Chapter 12. Adjunctive analgesics are also known as adjuvant analgesics, nontraditional analgesics, or unconventional analgesics.

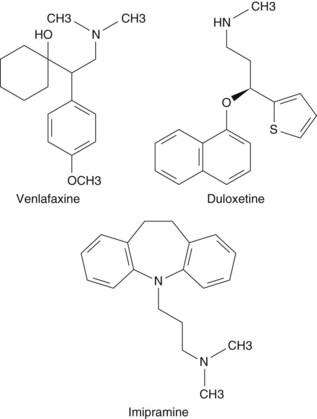

Adjunctive analgesics for chronic low back pain (CLBP) discussed in this chapter include the following two main drug classes, each of which contains several subclasses and specific medications: antidepressants (Figure 13-1) and antiepileptics.1,2

Numerous other types of medication are occasionally used for symptomatic relief of painful conditions such as CLBP, including corticosteroids, topical anesthetics, cannabinoids, α2-adrenergic agonists, and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists.1,2 Although these may also be considered adjunctive analgesics, they will not be discussed in this chapter.

Antidepressants

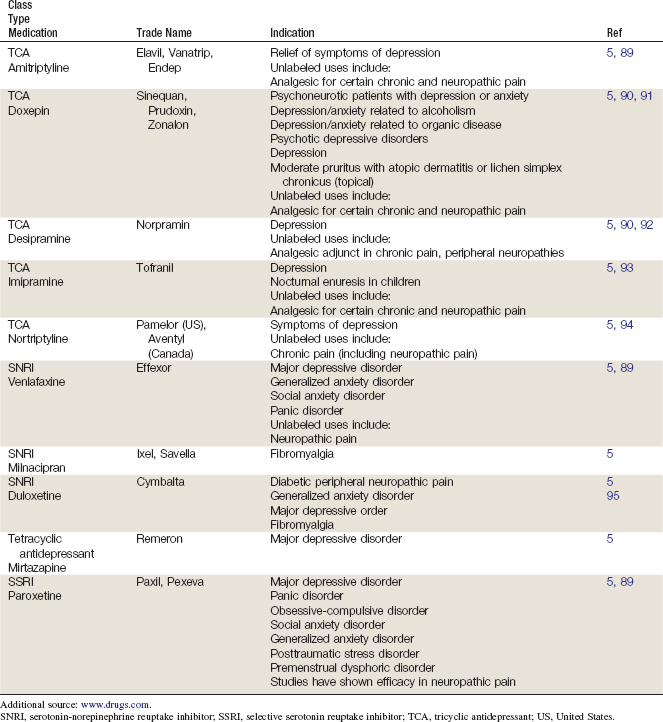

Tricyclic Antidepressants

There are different types of TCAs, and their classification has varied over time. Initially, a structural algorithm was used (e.g., tertiary vs. secondary amine TCAs). First-generation TCAs were tertiary amine TCAs, with a balanced inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake; these TCAs had adverse effects related to their anticholinergic activity. Subsequently, secondary amine TCAs were discovered, which selectively inhibited norepinephrine and had less toxicity.3 Secondary amine TCAs may also be referred to as noradrenergic TCAs, while tertiary amine TCAs may be referred to as balanced reuptake TCAs.4 TCAs include amitriptyline, amoxapine, clomipramine, dibenzepin, dosulepin hydrochloride, doxepin, desipramine, imipramine, lofepramine, maprotiline, nortriptyline, protriptyline, and trimipramine. Tetracyclic antidepressants include mirtazapine and maprotiline.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs include citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline; zimelidine is now available in the United States for the treatment of fibromyalgia.5

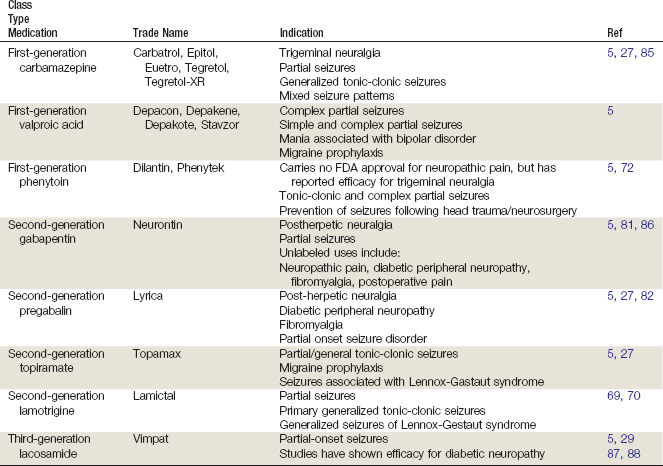

Antiepileptics

Antiepileptics are also known as anticonvulsants. There are three main categories of antiepileptics, named in chronological order of discovery: first generation, second generation, and third generation.6–8

History and Frequency of Use

Several types of medications have been used to manage symptoms of low back pain (LBP), including many that are no longer used (e.g., colchicine).9 Use of new medications to manage LBP often begins anecdotally, with clinicians observing their effects for other indications and extrapolating those results to how they may impact LBP. This appears to be the case with adjunctive analgesics, which have been used for at least 4 decades to manage LBP but appear to have grown in popularity in the past decade.10 An increasing use of adjunctive analgesics is likely due to a lack of long-term results when using traditional analgesics, prompting clinicians to try other approaches for patients with persistent symptoms. The use of antiepileptic medications as adjunctive analgesics for CLBP likely arose from their US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for neuropathic pain conditions such as postherpetic neuropathy (PHN) and diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN).

Medications are the most commonly recommended option for managing LBP and are prescribed to approximately 80% of patients presenting to a primary care provider.11 There are wide variations in prescribing patterns and little agreement among primary care providers on the optimal medication regimen for LBP; one third of patients with LBP are prescribed more than one medication. It was reported in 1985 that TCAs were prescribed by primary care providers to approximately 2% of patients presenting with LBP.9 More recently, it was reported that 12% of patients in Belgium with LBP were prescribed antidepressants, and 2% were prescribed antiepileptics.12 Use of antidepressants and antiepileptics for LBP appears to be higher in older adults; similar figures for adults older than age 60 were 17% and 3%, respectively. A study in Sweden asked 302 patients who presented to 16 physicians at 14 randomly selected outpatient clinics to complete questionnaires on health care resource use in the past 6 months.13 Antidepressants were the fifth most commonly used class of medication, reported by 8% of patients.

Theory

Mechanism of Action

The use of adjunctive analgesics for CLBP is based on its presumed etiology, which can broadly be divided into nociceptive or neuropathic pain.14,15 Nociceptive pain stems from any tissue injury that initiates a nociceptive signal carried by a nerve, and is thought to account for the vast majority of patients with CLBP. Neuropathic pain stems specifically from injury to the nerve itself, which likely contributes to the clinical presentation in only a small fraction of patients with CLBP. Nociceptive CLBP need not be confined to the lumbosacral area and may refer pain along the dermatomal distribution of a spinal nerve root or peripheral nerve. Neuropathic CLBP is radicular in nature and may be felt all along the area of sensory innervation for a spinal or peripheral nerve. The etiology of nociceptive pain is multifaceted and may result from any number of mechanisms of injury to the lumbosacral area, whereas the etiology of neuropathic pain is often due to inflammation secondary to infection, autoimmune, metabolic, or neurologic disorders. The distinction between neuropathic and nociceptive pain is crucial with respect to adjunctive analgesics for CLBP because some medications are intended solely for neuropathic pain and may have no effect in nociceptive pain.16

Table 13-3 compares some of the basic characteristics for nociceptive and neuropathic pain.

TABLE 13-3 Characteristics of Neuropathic and Nociceptive Pain

| Aspect | Neuropathic Pain | Nociceptive Pain |

|---|---|---|

| Quality | Numbness, tingling, burning | Dull, achy |

| Location | Discrete band of pain | Vague pain |

| Leg involvement | Pain often below knee | Pain often above knee |

| Neurologic deficit | Occasional | None |

| Dural tension | Positive | Negative |

Various adjunctive analgesics work along different sections of the pain pathway.17 Pain is activated through a veritable cornucopia of peripheral receptors, often producing a soup of inflammatory mediators that can perpetuate or amplify the nociceptive signal (e.g., bradykinin, leukotrienes, substance P). In patients with chronic pain, it is hypothesized that a windup phenomenon occurs in the dorsal horn, resulting in increased activity of NMDA receptors and activation of voltage-gated calcium channels. If this state endures, central sensitization via modulation of the spinal cord may eventually develop, with descending inhibition of the pain pathway at the spinal cord level. This phenomenon can slowly decrease the threshold required to trigger a nociceptive signal, resulting in greater and more frequent pain.14,18

Antidepressants

Tricyclic Antidepressants

TCAs are thought to provide relief for neuropathic pain via the serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways, perhaps due to their stabilization effects on nerve membranes.19 Although both pathways are involved in TCAs, the ratio of serotonergic to noradrenergic action may differ based on the individual medication. In vitro, TCAs demonstrate a mostly balanced inhibition of both serotonin and noradrenalin reuptake; in vivo, they are metabolized to secondary amines that primarily affect noradrenalin reuptake.20 Neuropathic pain relief with TCAs appears to occur independently of any antidepressant effect they may also produce.21 This is important to note because although the antidepressant effects of TCAs may take several weeks to develop, improvement of pain may occur substantially sooner. Titration of TCAs to an effective dose with tolerable side effects may take several weeks to achieve and require periodic reevaluation.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs prevent primarily the reuptake of serotonin into the synaptic cleft, thereby increasing available levels of this neurotransmitter. They may also affect other monoamine transporters related to dopamine and norepinephrine, but are not thought to act on their roles in pain pathways.22 SSRIs are therefore not indicated for neuropathic pain, and any clinical improvement noted in CLBP from their use is likely associated with improvement in secondary emotional disturbances such as depression, anxiety, or insomnia.21

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

SNRIs affect both serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways. Although mirtazapine has been referred to as a dual-action noradrenergic and specific serotonergic drug, significant serotonergic effects have not been demonstrated in humans.23 For venlafaxine, the balance between serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibition relates to dosage. Whereas lower doses of venlaxafine affect primarily serotonin pathways, higher doses affect mainly noradrenalin pathways.24 In contrast, duloxetine affects both serotonin and noradrenalin pathways in a manner regardless of dosage.25

Antiepileptics

First Generation

First-generation antiepileptics such as carbamazepine, valproic acid, and phenytoin are thought to act on the pain pathway through inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels26,27; carbamezepine may also have a stabilizing effect on neuronal membranes.26 Valproic acid also increases concentrations of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the brain.27 Carbamazepine is typically titrated from 100 to 200 mg to a maximum dose of 1200 mg daily and requires meticulous monitoring of blood levels due to its somewhat narrow therapeutic window.

Second Generation

Until recently, the mechanism of gabapentin was unknown. Gabapentin is classified as a ligand of the voltage-gated calcium channel α2-Δ subunit, and is structurally related to GABA, although it does not bind directly to GABA receptors and is not converted to GABA. It is thought to act at voltage-gated calcium channels and inhibit excitatory neurotransmitter release.27 Pregabalin is also classified as an α2-Δ ligand and an analog of GABA that similarly does not bind to GABA receptors and is not converted to GABA. It also acts at voltage-gated calcium channels.26 Topiramate is thought to block voltage-dependent sodium channels, potentiate GABA transmission, and inhibit excitatory neurotransmission. Lamotrigine’s proposed antinociceptive effects are attributed to sodium blockade and neural membrane stabilization, as well as to inhibition of the presynaptic release of glutamate.26

Gabapentin requires a slow titration, starting at 100 to 300 mg to a maximum dose of 3600 mg daily, typically divided into three or four doses. Pregabalin requires titration from 50 mg three times daily or 75 mg twice daily up to a maximum of 300 mg daily. It does not require as prolonged a titration because of its increased bioavailability and relatively linear pharmacokinetics. At doses of 300 mg/day, topiramate has been reported to alleviate CLBP by reducing pain symptoms and improving mood and quality of life.28

Third Generation

Lacosamide is an inhibitor of voltage-gated sodium channels and NMDA receptors.29

Table 13-4 provides a summary of the mechanism of action for different generations of antiepileptics.

TABLE 13-4 Mechanisms of Action for Different Antiepileptic Medications

| Medication | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|

| Carbamazepine | Inhibits voltage-gated Na++ channels |

| Gabapentin | Acts on voltage-gated Ca++ channels |

| Lamotrigine | Acts at Na++ and N-type Ca++ channels |

| Oxcarbazepine | Blocks voltage-gated Na++ channels May affect C++ and K++ conductance |

| Phenytoin | Inhibits voltage-gated Na++ channels |

| Pregabalin | Acts on voltage-gated Ca++ channels |

| Topiramate | Acts on voltage-gated Na++ channels Potentiates gamma amino butyric acid transmission Blocks AMPA/glutamate transmission |

AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid.

Assessment

Before receiving adjunctive analgesics, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating these interventions for CLBP. Prescribing physicians should also inquire about medication history to note prior hypersensitivity/allergy or adverse events with similar drugs, and evaluate contraindications for these types of drugs. Clinicians may also wish to order a psychological evaluation if they are concerned about the potential for medication misuse or potential for addiction in certain patients. Diagnostic imaging or other forms of advanced testing is generally not required before administering adjunctive analgesics for CLBP.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Antidepressants

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found that both noradrenergic and noradrenergic-serotonergic antidepressants can be considered as management options for the symptomatic relief of CLBP.30 That CPG also found moderate evidence that neither noradrenergic nor noradrenergic-serotonergic antidepressants are effective with respect to improvements in function.

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found conflicting evidence of a moderate effectiveness for both noradrenergic and noradrenergic-serotonergic antidepressants.12

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 found that SSRIs should not be used.31 That CPG also found conflicting evidence concerning the effectiveness of TCAs with respect to improvements in reducing pain and concluded that TCAs could be considered as one management option for CLBP if other medications do not provide sufficient symptomatic relief.31

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found evidence of a small to moderate benefit for antidepressants with CLBP.32

Antiepileptics

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found limited evidence for the efficacy of gabapentin compared with placebo and did not recommend its use.30

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found low-quality evidence supporting the effectiveness of gabapentin.12

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found weak evidence to support the efficacy of gabapentin for CLBP with radiculopathy.32 That CPG also found insufficient evidence to support topiramate for CLBP.

Findings from these CPGs are summarized in Table 13-5.

TABLE 13-5 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Adjunctive Analgesic Use for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants | ||

| 30 | Europe | TCAs and SNRIs can be considered as management options for the symptomatic relief of CLBP. Neither is effective with respect to improvements in function |

| 12 | Belgium | Conflicting evidence of moderate effectiveness for both TCAs and SNRIs SSRIs were not recommended |

| 31 | United Kingdom | SSRIs were not recommended |

| 31 | United Kingdom | TCAs can be considered if other medications do not offer relief |

| 32 | United States | Evidence of small to moderate benefit |

| 96 | Australia | Antidepressants were not recommended |

| 97 | Sweden | Antidepressants were not recommended |

| Antiepileptics | ||

| 96 | Australia | Antiepileptics were not recommended |

| 30 | Europe | Gabapentin was not recommended |

| 12 | Belgium | Low-quality evidence supporting the use of gabapentin |

| 32 | United States | Weak evidence supporting efficacy for gabapentin |

| 32 | United States | Insufficient evidence to support the use of topiramate |

CLBP, chronic low back pain; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Systematic Reviews

Antidepressants

Cochrane Collaboration

The Cochrane Collaboration conducted an SR in 2008 on antidepressants for nonspecific LBP.33 A total of 10 RCTs were included that compared antidepressants with placebo; 9 included patients with CLBP, while 1 did not specify the duration of LBP.34–43 Overall, the review found inconsistent evidence regarding antidepressants on pain relief in CLBP, with a meta-analysis of six small RCTs giving a standard mean difference (SMD) of −0.04 (95% CI −0.25 to 0.17). The review also concluded that there is no consistent evidence that antidepressants reduce depression in CLBP patients, or that antidepressants improve functional status in LBP patients. Furthermore, there was no difference between two types of antidepressants (TCAs and SSRIs) and placebo in pain relief.

American Pain Society and American College of Physicians

An SR was conducted in 2007 by the American Pain Society and American College of Physicians CPG committee on medication for acute and chronic LBP.11 That review identified 3 SRs related to antidepressants and LBP, which included 10 unique RCTs.44–46

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree