Acute Urology

Stanley J. Kogan MD

Penny Colbert-Kogan RN, BSN

INTRODUCTION

Genitourinary (GU) problems are frequently encountered in general pediatric practice. With the prenatal diagnosis of GU problems made in 0.1% to 1% of pregnancies (Johnson et al., 1992) and the presence of cryptorchidism found in about 3% of term boys (Gill & Kogan, 1997), primary care providers are commonly expected to have basic knowledge of these and related conditions. Urinary tract infections (UTIs), occurring in 1% to 2% of school girls; vesicoureteral reflux; acute scrotal inflammation; and penile disorders all constitute additional frequently encountered problems demanding basic expertise. This chapter provides information for understanding, recognizing, referring, and treating patients with these problems.

CONGENITAL HYDRONEPHROSIS, MULTICYSTIC KIDNEY, AND VESICOURETERAL REFLUX

Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology

Abnormal ureteral bud development is the clue to understanding congenital hydronephrosis, multicystic kidney, and vesicoureteral reflux. At about the 4 mm embryonic stage, the ureteral bud grows out of the cloaca (which ultimately forms the bladder and rectum) cephalad into the developing metanephric cell mass (which ultimately forms the kidney). According to one theory (Mackie & Stephens, 1975), if the bud enters the metanephric cell mass in too cranial of a position, an obstructed or cystic kidney will result. If it enters in too caudal (inferior) a position, kidney dysplasia is the consequence. At the same time, if the lower end where the ureteral bud originates grows out of the cloaca from a lateralized position, the resulting tunnel through the subsequent bladder wall is too short. Vesicoureteral reflux is the outcome.

The cysts in multicystic kidneys vary in size and usually do not communicate with one another. Often the ureter is atretic or absent, and there may be no renal pelvis. Obstruction leads to progressively abnormal branching of the developing calyces and thinning of the renal parenchyma, changes that ultimately affect renal function.

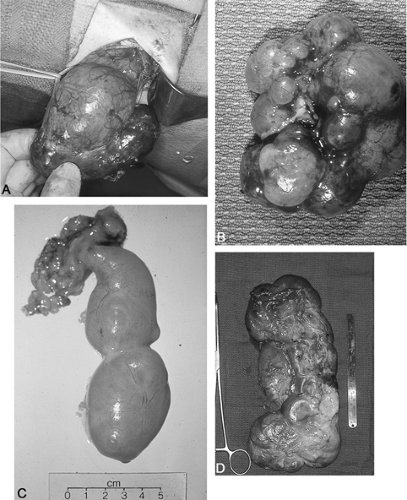

Fortunately, many neonatally confirmed ureteropelvic junction obstructions have a huge distended renal pelvis with relatively well preserved parenchyma. The distensible pelvis “protects” the parenchyma from markedly increased pressures, at least for a while, and renal function is initially preserved in many (Fig. 40-1).

Epidemiology

Whereas only a few decades ago, the usual presentation of hydronephrosis was as a silent abdominal mass, now virtually all are discovered prenatally. Most cases are cystic or hydronephrotic kidneys, with obstruction or underlying vesicoureteral reflux as the cause. Physiologic dilatation, which spontaneously subsides in the postnatal period, constitutes another significant group of patients.

Some cystic diseases of the kidneys and vesicoureteral reflux are associated with genetic tendencies. Reflux risk is increased in some families, especially those with blond females and of Scandinavian descent.

The overall risk of a sibling having reflux when it has been identified in an index patient increases to about one in four in some series, even if there is no history of urinary infection. This fact should prompt the clinician to investigate the possibility of reflux in at-risk siblings of an affected child.

Similarly, there is a significant increased genetic risk involved with autosominal dominant, “adult polycystic” (AD-PKD) and autosomal recessive, “infantile polycystic” kidney disease (AR-PKD). If a parent has AD-PKD, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease. If neither parent has the disease, none of the children will inherit the disease, even if history of the disease is in the family. With AR-PKD, if both parents have the recessive gene, one in four children can inherit the disease despite no findings of the disease in the parents. Multicystic kidney disease, which is the most common variety of cystic disease seen in children, occurs sporadically and is not associated with an increased genetic risk.

History and Physical Examination

Most cases are now diagnosed prenatally. Occasionally, an abdominal mass may be evident at birth or become evident subsequently. Providers should observe the urinary stream and seek evidence for bladder distension in males. Urinary infection may occur sometime during the first year of life or after and usually is a sign of underlying vesicoureteral reflux. Children with multicystic kidneys have an increased risk (between 10% and 20%) of associated vesicoureteral reflux.

Diagnostic Criteria

Because there are usually no symptoms or physical findings, the diagnosis is usually based on prenatal sonography. Postnatal radiologic studies are indicated for any child with a history of prenatal urinary tract dilatation, because the frequency of underlying pathology is significant.

• Clinical Pearl

For unilateral hydronephrosis, it is best to defer postnatal sonographic imaging until 2 to 3 weeks after birth. Sonography during the first few days after birth notoriously underestimates the extent of hydronephrosis because newborns lose a significant amount of water weight. Later imaging more accurately indicates the true extent of the problem.

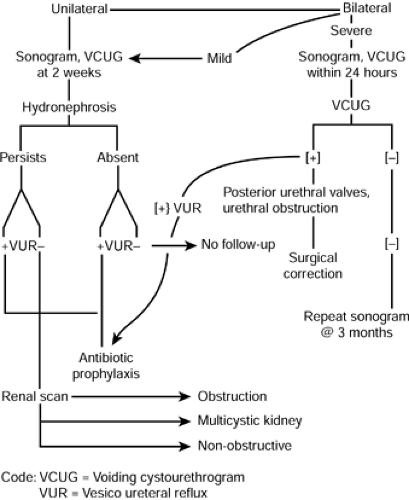

If bilateral hydronephrosis is present and severe at birth, a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) and sonogram should be performed within 24 hours of birth to determine whether outlet obstruction is present (posterior urethral valves in boys and ureterocele or urethral/urogenital sinus obstruction in girls).

A VCUG is indicated in all instances of prenatally diagnosed hydronephrosis to determine the presence of vesicoureteral reflux and to image the urethra in males. If kidney obstruction is suspected, a renal scan is indicated at times to confirm obstruction in a dilated kidney and to quantitate kidney function and excretion. This study is not usually done before age 3 to 4 weeks, because neonatal glomerular filtration rate is markedly decreased initially and does not normalize completely until about age 6 months. Multicystic kidneys typically are found to be devoid of all function, as are some dysplastic kidneys. Diminished function in a nonrefluxing hydronephrotic kidney usually indicates significant obstruction. Figure 40-2 refers to an algorithm for the evaluation of prenatal hydronephrosis.

Management

Reflux

When reflux is documented, antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated as initial treatment for all grades except the most severe (grade V). Antibiotics do not cure reflux; rather, they prevent urinary infections from occurring. Treatment is based on the premise that reflux will often disappear spontaneously by ages 4 to 6 years in most instances, providing that no breakthrough urinary infections occur. Reflux without urinary infection usually does not damage the kidney. As determined on the VCUG, the lower the reflux grade, the more likely the reflux will ultimately self-cure (American Urological Association, 1997).

The sonogram and VCUG are repeated 12 to 15 months later. Reflux persisting beyond ages 4 to 6 years usually requires surgical correction, because reflux persisting thereafter has a markedly reduced chance of spontaneous resolution. When surgical correction is required, the ureter is reimplanted into the bladder in a manner to lengthen its course through the bladder wall, enabling it to act in a one-way-valve

fashion. Surgical methods vary, but all now are associated with a reduced hospital stay, usually varying between 1 and 4 days. Results of surgery are highly successful; once the reflux is corrected, it is very unlikely to recur.

fashion. Surgical methods vary, but all now are associated with a reduced hospital stay, usually varying between 1 and 4 days. Results of surgery are highly successful; once the reflux is corrected, it is very unlikely to recur.

Multicystic Kidneys

Multicystic kidneys are functionless on renal scan. Most will involute with time, literally “shriveling” into a minute or indiscernible mass on follow-up sonography. Observant follow-up with periodic sonography is the appropriate initial treatment. Rarely, multicystic kidneys will grow, sometimes to very significant size, requiring surgical excision. Hypertension, infection, and neoplastic change are additional rare causes for nephrectomy. Conventional large incisions are no longer needed for nephrectomy in infants with multicystic kidneys. Mini-incision nephrectomy and laparoscopic nephrectomy now allow for markedly reduced morbidity and even same-day surgery in many instances.

Obstruction

Considerable judgment is required with kidneys demonstrating an obstructive pattern on renal scan. For those that are clear-cut, pyeloplasty for relief of ureteropelvic obstruction should be done as soon as the infant is thriving and fit, usually between ages 1 and 2 months. Early repair is feasible in skilled pediatric urologic hands when skilled pediatric anesthesia can be provided as well. This approach maximizes preservation of renal function.

Infants demonstrating an “equivocal” or indeterminate pattern on renal scan should be followed carefully by follow-up sonography in 3 and in 6 months with an additional renal scan if necessary. Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated for the more severe cases, although not all practitioners uniformly recommend this approach. If follow-up imaging indicates deterioration, surgical correction is indicated, because obstruction is usually progressive and compromises renal function. Pyeloplasty is eminently successful in childhood and preserves renal function from further deterioration.

What to Tell Parents

Parents must be counseled that continued low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis is important because omission increases the risk of febrile UTIs and kidney damage. Repeated radiologic imaging is essential and cannot be omitted. Chronic (albeit infrequent) follow-up is essential because late deterioration does occur.

SCROTAL AND TESTICULAR ABNORMALITIES

Developmental disorders predispose testes to later problems. Boys with abnormally descended testes are subject to rapid germ cell loss and ultimate sterility if the problem is not corrected early in life. Scrotally located testes with abnormal fixation are subject to increased risk of testicular torsion, atrophy, and subfertility. A persisting processus vaginalis and hydrocele may expand with time into a hernia, necessitating surgical correction. Knowledge of childhood scrotal and testicular problems is essential in preventing later health mishaps and medicolegal problems.

For all problems involving the scrotum and testes, the primary care practitioner will need to consider various diagnoses and interventions. Scrotal swelling may be caused by a hydrocele, hernia, testicular torsion, torsion of the appendix testis, epididymitis, varicocele, hematocele, and rarely tumors. Loss of a testicle may be a tragic consequence if diagnosis of testicular torsion is missed. The following is a list of general considerations that may be useful in establishing the correct diagnosis and consequent course of action.

Determine the following about the swelling:

Acute or chronic

Painful or painless

Fluctuating in size or stable

Associated with GU symptoms, systemic symptoms, or trauma

On physical examination, note the following:

Look for signs of inflammation (eg, erythema, heat, swelling, tenderness).

Determine if the swelling is moveable, reducible, present only in upright position.

Transilluminate to determine if swelling is lucent (fluid-filled) or solid.

Cryptorchidism

Pathology

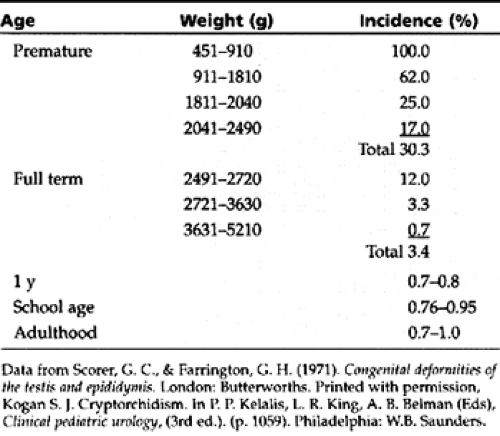

Testicular descent is a function of fetal development and correlates with gestational age and fetal weight. Cryptorchidism occurs in about one in three premature boys. By term, most testes will descend, with about 3% remaining

cryptorchid. Probably resulting from the physiologic burst in testosterone noted in boys at age 6 to 8 months, most testes that are cryptorchid at birth descend subsequently, with only 1% remaining cryptorchid at age 1 year (Table 40-1).

cryptorchid. Probably resulting from the physiologic burst in testosterone noted in boys at age 6 to 8 months, most testes that are cryptorchid at birth descend subsequently, with only 1% remaining cryptorchid at age 1 year (Table 40-1).

If not treated within the first year, germ cells rapidly deteriorate. At 2 years, about one third of untreated cryptorchid testes are completely devoid of germ cells, one third have significant germ cell loss, and one third have testes with normal germ cell numbers (Houissa, dePape, Diebold, et al., 1979). Testes remaining cryptorchid at puberty are uniformly oligospermic or azospermic. Leydig cell function usually remains adequate, though persistent cryptorchid adults may suffer premature androgen failure.

Because spontaneous descent occurs minimally beyond age 1 year and the onset of deterioration is noted at the same time, medical or surgical treatment is indicated by the first birthday (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1997).

History and Physical Examination

When evaluating cryptorchid testes, clinicians should determine whether a parent has ever visualized the testis in the scrotum. Surprisingly, parents or older boys often know that the testicle has been felt within the scrotum even though the testis is not evident during the pediatric office examination. Testicular retraction causes confusion in diagnosis. Some boys have a hyperactive cremasteric muscle reaction, causing a truly descended testis to retract rapidly into the inguinal region at the slightest provocation (retractile testis).

• Clinical Pearl

Retraction may be avoided if the clinician places two fingers over both inguinal rings before examining the scrotal contents, thereby blocking testicular escape into the canal.

Another technique involves positioning the boy crosslegged and leaning forward, which relaxes the cremasteric muscles and often allows the testicle to fall into the scrotum and become palpable. If these means do not place the testicle in the scrotum, true cryptorchidism exists. Making this distinction is important because retractile testes usually develop normally, and conversely, treatment must be provided to truly cryptorchid testes to prevent deterioration.

Besides this distinction, secondary or delayed ascent of a previously descended testis occurs in about 5% of cryptorchid boys, further confounding diagnosis. These testes are exposed to the same risk of deterioration as those that are congenitally cryptorchid, though occurring at a slower rate. Retraction of the testis may occur due to reabsorption of an occult patent processus vaginalis (PPV) (Rabinowitz & Hulbert, 1997). Examination and documentation of the position of both testes through the end of pubertal development is absolutely essential to prevent medicolegal problems in these instances. In the case of retractile testes, the clinician should document and demonstrate to the parent their scrotal position at each preventive visit.

Diagnostic Criteria

About 20% of all cryptorchid testes are impalpable despite all posturing and positioning maneuvers. Impalpable testes are either present within the abdomen or inguinal canal, or they are atrophic or absent. Bilateral impalpable testes in a phenotypic male should raise the suspicion of an occult female adrenogenital syndrome.

Diagnostic Studies

When testes are impalpable, inguinal, pelvic, and scrotal ultrasound can be used to aid in diagnosis. Technical limitations sometimes occur, limiting the reliability, and “negative” sonograms have been seen indicating an absent testis when the testis was easily palpable in the groin or scrotum. A sonogram indicating that an impalpable testis is actually present is usually accurate. If the sonogram does not iden-tify a testis, an impalpable testis may still be present (false-negative examination). In these instances, laparoscopy preceding surgical exploration is the most reliable test to determine whether the testis is present. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging examinations are not routinely used in these instances because they are costly and not completely reliable and diagnostic. In highly selected cases (ie, in which a previous surgical exploration failed to reveal an impalpable testis) these examinations may have some utility (Kogan, 1992).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree